Table of Contents

In One Moment, Time Stood Still

There is a melody that flows across piano keys. Notes without time signatures, without bar lines, floating as if they’ve erased the boundaries of time itself. When you hear that sound, where do you find yourself? In some cabaret in late 19th-century Montmartre, or perhaps within the labyrinth of ancient Crete?

Erik Satie’s Gnossienne No. 1 is such music. Each time you listen, it makes you lose track of time and place, thus allowing you to dwell in eternity. Born around 1890, this piece transcends being merely a beautiful piano miniature—it was a revolutionary manifesto that changed the entire direction of musical history.

The Music Academy Dropout Who Became a Rebel

If you’re hearing Erik Satie’s name for the first time, you should probably start with his life story. Born in 1866 in Honfleur, France, he earned the ignominious title of “the laziest student” at the Paris Conservatoire. But behind that laziness lay fundamental questions about existing musical education.

Satie wondered why music had to follow the massive emotional outpourings and complex harmonic progressions of German Romanticism. In an era dominated by Wagner’s overwhelming sonorities and heavy philosophy, he pursued instead the aesthetics of simplicity and empty space. “Why must music be so complicated? Why must it explain so much?”

In 1890, while working as musical director at the Chat Noir cabaret in Montmartre, he began constructing his own musical world. In that gathering place of bohemians and artists, Satie boldly abandoned traditional musical forms and created an entirely new language. And the first fruit of this endeavor was Gnossienne No. 1.

Even the Name Is an Enigma

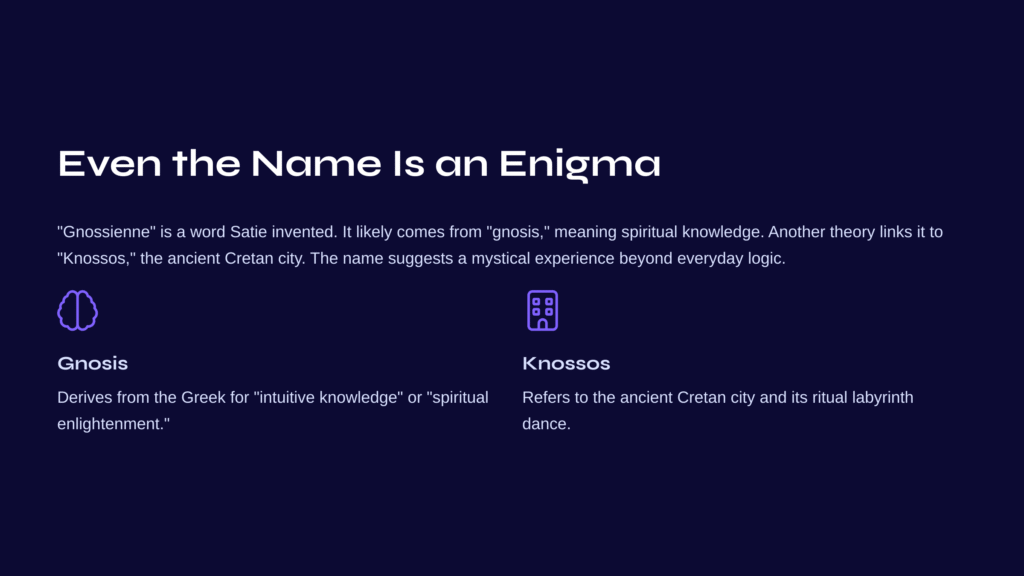

It’s futile to look up the word “Gnossienne” in any dictionary. It’s a neologism created by Satie himself. It’s extremely rare in musical history for a composer to invent an entirely new word to create a new genre.

There are several interpretations of this mysterious title. The most plausible explanation is that it derives from the Greek “gnosis,” meaning “intuitive knowledge” or “spiritual enlightenment.” In the early 1890s, Satie served as the official composer for the Rosicrucian movement, a mystical organization, and was deeply immersed in Gnostic and esoteric philosophy. For him, music was not mere entertainment but a tool for spiritual awakening.

Another explanation suggests it derives from “Knossos,” the ancient Cretan city. Archaeological excavations of the Knossos palace were actively underway around the time Satie composed this piece. The 1865 Larousse dictionary records that Theseus created a ritual labyrinth dance called “gnossienne” after defeating the Minotaur.

Either way, what this title contains is clear: a longing for mystical experiences that transcend time and space, and for spiritual exploration beyond everyday logic.

Revolution Begins Quietly

Any performer seeing the score of Gnossienne No. 1 for the first time cannot help but be bewildered. There are no time signatures. No bar lines. Instead, notes float freely, entrusting the flow of time to the performer. This was an unimaginable innovation in 1890.

Traditional Western music thoroughly structures time. 4/4 time, 3/4 time… within such frameworks, notes move with precise positioning. But Satie asked, “Why must music be as regular as clockwork?” And instead of seeking an answer, he posed an entirely different question: “What if music doesn’t follow time, but creates it?”

Gnossienne No. 1 is precisely such music. While the piece progresses, we forget clock time. Instead, we fall into the unique time created by the music—the time of breathing, the time of meditation. The left hand’s gentle accompaniment flows like waves beneath the right hand’s melody, a flow that is unpredictable yet completely natural.

Poetic Instructions for the Performer

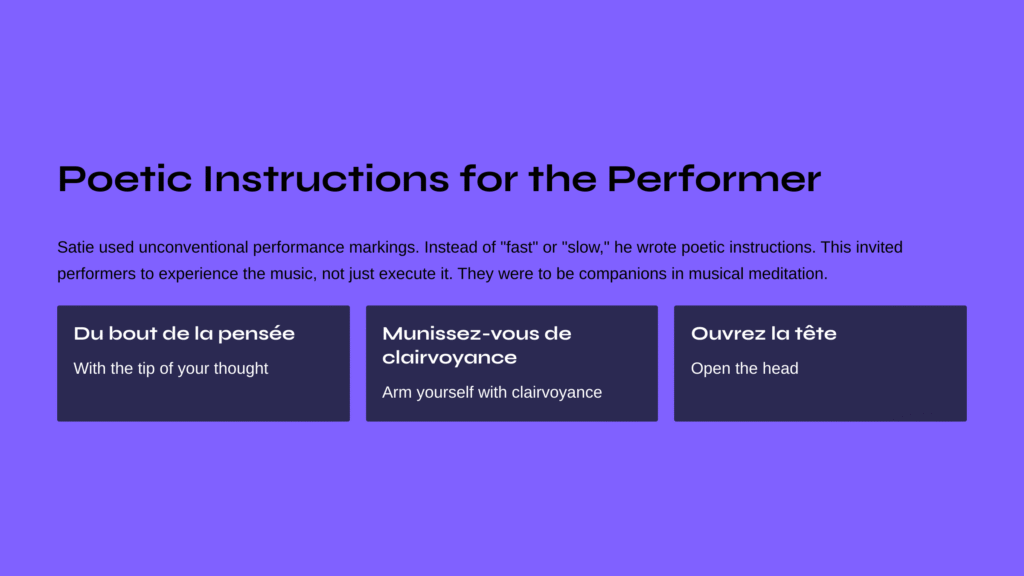

Another of Satie’s innovations lies in his performance markings. Typically, classical scores contain traditional tempo indications like “Allegro (fast)” or “Andante (walking pace).” But Gnossienne contains instructions like these:

“With the tip of your thought (Du bout de la pensée)”

“Arm yourself with clairvoyance (Munissez-vous de clairvoyance)”

“Open the head (Ouvrez la tête)”

“Very lost (Très perdu)”

“With astonishment (Avec étonnement)”

What must a performer feel upon first seeing such markings? A message to rely on inner intuition rather than technical precision. An invitation not simply to “perform” music but to “experience” it. Satie wanted performers to become companions in musical meditation, not mechanical executors.

Eastern Fragrance Hidden in Melody

When you listen to the piece, there’s something strangely Oriental about it. This is because he used ancient modes rather than Western major or minor scales. Dorian mode, Phrygian mode… these terms might seem difficult, but simply put, they’re the special colors you can hear in medieval church music or Eastern music.

The melody circulates like drawing a circle. Not the traditional Western structure of “beginning-development-climax-resolution,” but meditative patterns that revolve endlessly. Like a Zen koan, the same melody repeats while revealing slightly different meanings each time.

The left hand’s accompaniment is regular yet hypnotic. Like a rocking cradle, like the rhythm of waves hitting the shore. Above this, the right hand’s melody dances freely like a bird. Sometimes it descends in melancholy, sometimes it rises like hope. But none of these movements feel forced. They flow naturally, like breathing.

The Magic I Feel in Gnossienne

When I listen to this piece, I always have the same imagination. A misty dawn, playing piano alone in an empty library. Or perhaps twilight in an old cathedral, beneath the last rays of sunlight streaming through stained glass. Gnossienne is music for such solitary moments.

But that solitude isn’t lonely. Rather, it’s fulfilling. Just as we can only hear our true voice when alone, this music allows us to face our inner quietude. The noisy clamor of the world momentarily stops, gifting us time to dialogue with something deeper within ourselves.

Sometimes this piece seems to pose questions: “Where are you now? Are you really there? Or do you want to journey somewhere else?” And it doesn’t rush for answers. It simply gives us time to be with those questions.

Small Secrets for Deeper Listening

I’d like to offer some tips for those listening to Gnossienne No. 1 for the first time.

First, don’t listen in haste. If you try to appreciate this piece quickly, you’ll miss its true value. Set aside at least 10 minutes, stop everything else, and listen in a comfortable position with your smartphone turned off.

Second, don’t fear repetition. Satie’s music cannot reveal its depth in a single hearing. Feel how slightly different emotions arise each time the same melody returns. Like turning a kaleidoscope to reveal new patterns each time.

Finally, don’t seek the perfect performance. Gnossienne isn’t a piece for showing off technique. Rather, performances where the performer’s sincere emotions emerge are better. Comparing different interpretations by pianists like Pascal Rogé, Anne Queffélec, and Reinbert de Leeuw would also be interesting.

Music’s Gift That Transcends Time

More than 130 years have passed since Gnossienne No. 1 was composed, but this piece remains contemporary. The fathers of minimalist music like Steve Reich and Philip Glass drew inspiration from this piece, and its influence can be found in film music and video game soundtracks. Even the roots of contemporary ambient and New Age music can be traced here.

The questions Satie posed remain valid today. Must music necessarily be complex? Do we need massive orchestras to express emotion? Or sometimes, is a simple piano sufficient?

Gnossienne No. 1 proves the paradox that “less is more.” Without flashy technique or dramatic development, this piece touches the deepest places in listeners’ hearts. Like a small stone thrown into a quiet lake creating wide ripples.

Melody Leading to Eternity

Each time I listen to Gnossienne, I wonder: what exactly is music? Is it a succession of sounds flowing through time, or something eternal that transcends time? Satie’s music is closer to the latter. His melodies approach us as if they had always existed, without clear beginnings or endings.

It’s no coincidence that this one small piano piece changed musical history. It touched humanity’s most fundamental desire—the longing to stop time and dwell in eternity. Even amid busy daily life, even within complex human relationships, we sometimes need such quiet moments.

Gnossienne No. 1 is music for such moments. Whenever and wherever you listen to this piece, in that moment time will stop, and you’ll gain your own small enlightenment within the mysterious space created by the music. And that experience will linger long in your heart as an echo, even after the piece ends.

This is precisely the gift Erik Satie gave us. Music that transcends time, music for the soul, and music that leads us to find true quietude.

Journey to the Next Piece: Bizet’s Carmen Suite No. 1 “Toreadors”

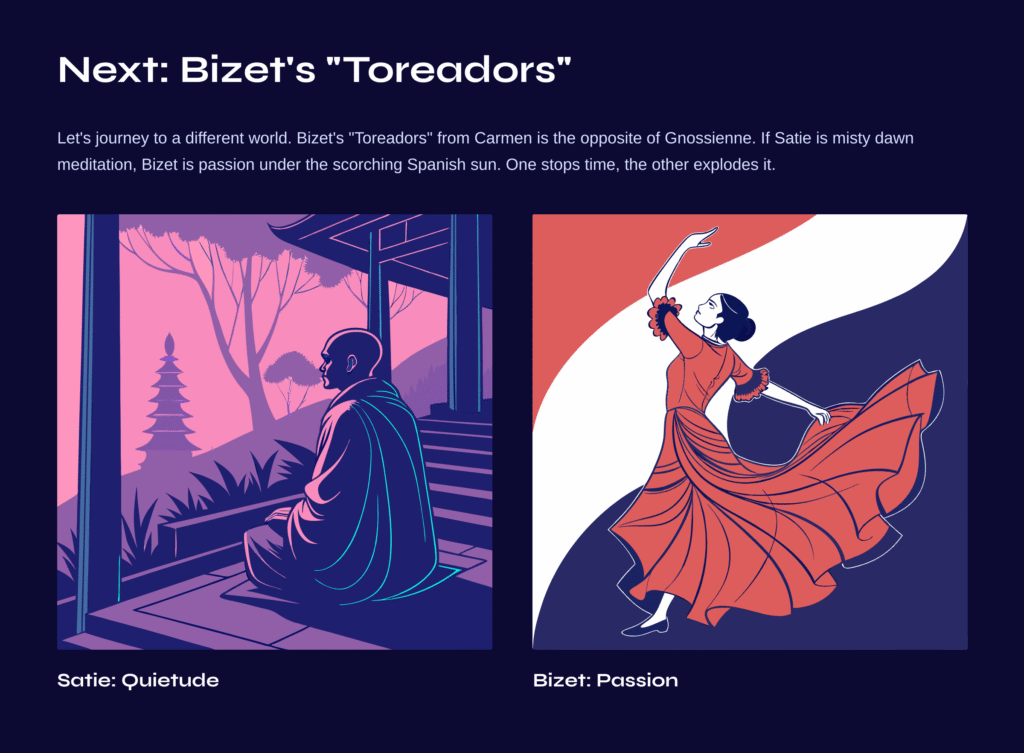

Let’s escape from Satie’s mysterious quietude and journey to a completely different world. Georges Bizet’s “Toreadors” from Carmen Suite No. 1 possesses a charm completely opposite to Gnossienne.

If Gnossienne is meditation in a misty dawn, Toreadors is passion in the bullring under the scorching Spanish sun. Interestingly, both pieces share the common trait of working “temporal magic.” If Satie stops time, Bizet compresses and explodes it.

Beginning with the trumpet’s confident declaration, Toreadors instantly transports us to the hot streets of 19th-century Seville. The driving force of rhythm, the sensual curves of melody, and the spectacle created by the entire orchestra. If Gnossienne was a “journey inward,” Toreadors is “pulsation into the world.”

Listen to both pieces consecutively. Quietude and passion, meditation and festival, secrecy and splendor. In this stark contrast, you’ll newly realize how music can contain such diverse human emotions. As if a monk and a dancer live together within one person.