Table of Contents

A Melody’s Intimate Confession

Some music transports you to another world from the very first measure. Massenet’s “Méditation from Thaïs” is precisely such a piece. The gentle arpeggios of the harp slice through the quiet air, and the violin melody that follows whispers like someone’s secret confession in your ear. Within these brief five minutes of music lies every complex emotion the human heart can feel. Sacred and sensual, salvation and corruption, restraint and passion—all balanced precariously on a single melodic line.

When Massenet composed this piece in 1893, was he simply creating an operatic intermezzo? Or did he already know that this melody would one day touch countless souls and become a beacon of hope even amidst the ruins of war?

A Tale of Fallen Courtesan and Fanatical Monk

The plot of the opera “Thaïs” is more complex than it appears. It tells the story of Thaïs, a high-class courtesan in 4th-century Alexandria, and Athanaël, the monk who seeks to redeem her. What’s fascinating is the ambiguity of who truly needs salvation. Thaïs is drowning in physical pleasure while Athanaël is consumed by religious fanaticism. Both stand at opposite extremes.

Massenet must have pondered how to express such complex psychological conflict through music. Thus was born this “Méditation.” In Act II of the opera, as Thaïs reflects on her life and undergoes an inner transformation, no one sings on stage. Instead, the orchestra—particularly a single violin—speaks for her heart.

The piece premiered on March 16, 1894, at the Paris Opera. Though Sibyl Sanderson, Massenet’s beloved soprano, portrayed Thaïs that night, in this scene it’s the violin, not her voice, that tells the whole story.

A Praying Violin, A Wavering Heart

The structure of this piece is remarkably intricate. Following an ABA’ form, it flows as: “initial melody → transformation → variation of the initial melody → conclusion.”

First Section: Tranquil Beginning As the harp creates beautiful waves in D major, the violin enters cautiously. This melody is mysteriously captivating. Though seemingly simple, it employs Gregorian chant modes, lending an ancient, sacred quality. The violin’s gradual ascent from D sounds like a praying soul reaching toward heaven.

Second Section: Waves of Passion But the music soon begins to churn. Modulating to B minor, the melody becomes more complex and emotional. Marked “poco a poco appassionato” (gradually becoming passionate), the violin becomes fierce, as if pouring out inner turmoil. The orchestra swells alongside, painting Thaïs’s confused state of mind.

Third Section: Resignation and Acceptance We return to the initial melody, but now it’s different—shorter, quieter, somehow resigned. The violin’s final phrases, played in harmonics, create an ethereal effect as if dissolving into air. Surprisingly, the piece concludes in major. Yet whether this ending represents true resolution remains ambiguous. Those familiar with the opera’s tragic conclusion understand how fragile this quiet hope truly is.

A Melody of Hope Blooming Amidst War

This piece gained profound significance in the 20th century through two harrowing historical moments, transforming from mere operatic music into a symbol of human dignity.

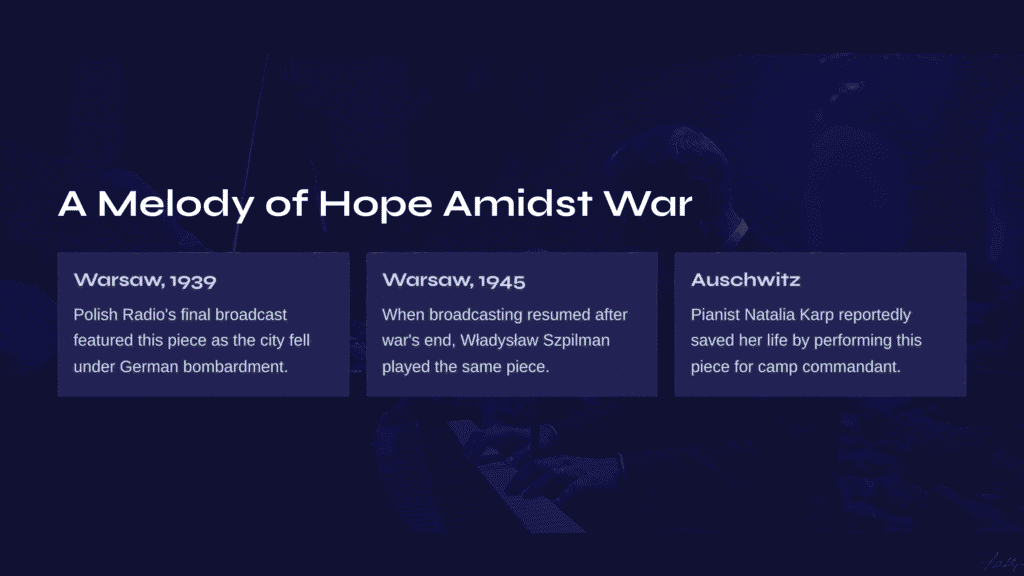

On September 23, 1939, as Warsaw fell under German bombardment, Polish Radio’s final broadcast featured this piece. Pianist Władysław Szpilman performed it, and how heartbreaking must that tender melody have been amid the explosions. Six years later in 1945, when broadcasting resumed after the war’s end, Szpilman played the same piece. Roman Polanski’s film “The Pianist” immortalizes his story.

Another tale exists: Jewish pianist Natalia Karp reportedly saved her life by performing this piece for Auschwitz commandant Amon Göth. The power of music to preserve humanity even before ultimate evil—perhaps that’s the true meaning of this piece.

What This Music Means to Me

When I first heard this piece, strangely I felt comfort rather than sadness. The violin’s melody seemed sometimes like prayer, sometimes like sighs, sometimes like an embrace. Particularly when the music intensifies in the second section, I felt I could understand Thaïs’s heart—that feeling of being torn between two entirely different worlds.

The greatest emotion this piece evokes is its refusal to provide perfect answers. Even after listening to the end, we don’t know if Thaïs was truly saved or if Athanaël achieved genuine enlightenment. It simply captures human complexity and contradictory hearts exactly as they are. That’s what makes it feel so authentic.

How to Listen More Deeply

For those hearing this piece for the first time, I recommend focusing on several key elements.

First, listen carefully to the violin’s bowing technique. Massenet marked it “cantabile”—”in a singing manner.” Truly skilled performers make the violin imitate the human voice. You can hear the breathing points, the moments when emotions shift, expressed with exquisite sensitivity.

Second, pay attention to the background created by harp and strings. This accompaniment, like cathedral reverberation, makes the violin melody shine even brighter. The dissonances that appear mid-piece are devices expressing Thaïs’s inner conflict.

Third, compare different recorded versions. Interpretations by modern performers like Anne-Sophie Mutter or Joshua Bell differ markedly from those of earlier artists like Jacques Thibaud. Older recordings use more portamento (sliding between notes) for a more romantic feel, while contemporary performances tend toward restraint and elegance.

A Prayer Beyond Time

Massenet’s “Méditation from Thaïs” is ultimately about time itself. Past and present, eternity and moment, memory and dream converge on a single melodic line. This five-minute piece depicting one woman’s inner journey has moved hearts for over a century precisely because of this temporal transcendence.

Sometimes we all stand at crossroads like Thaïs, uncertain which choice is right or which path leads to salvation. When listening to this piece in such moments, it seems to whisper: don’t struggle to find answers—simply accept the confusion and beauty of the present moment.

Perhaps salvation isn’t about finding perfect answers but learning to love our imperfect selves. As the violin’s final melody dissolves into silence, we quietly grasp this truth.

Also Worth Hearing: Chopin’s Nocturne No. 20 in C-sharp Minor

If you wish to explore further the poignant, nostalgic emotions felt in Massenet’s “Méditation,” I recommend Chopin’s Nocturne No. 20. This piece also appears at a crucial moment in “The Pianist.”

Where “Méditation” uses a single violin to sing of the soul’s conflict, Chopin’s nocturne whispers solitude and longing through piano keys. Both are brief pieces, yet the emotional depth they contain surpasses any grand symphony. Particularly, Chopin’s characteristic rubato (flexible tempo) and Massenet’s portamento create similar temporal flows.

The beauty that blooms even within C-sharp minor’s dark, complex tonality—that’s the aesthetic these two pieces share. If “Thaïs” left your heart heavy, try listening to Chopin’s nocturne in solitude. You’ll encounter the same longing, but tears of a different color.