📑 Table of Contents

The Premiere That Changed Music Forever

Vienna, May 7, 1824. The Kärntnertortheater is packed to the rafters. On stage stands a disheveled man with wild gray hair, his back to the audience, waving his arms in passionate gestures that seem disconnected from the orchestra’s sound. When the final thunderous chord fades into silence, the audience erupts—cheering, weeping, throwing hats into the air. But the conductor doesn’t turn around.

A soloist gently touches his shoulder and guides him to face the crowd. Only then does Ludwig van Beethoven see the standing ovation, the handkerchiefs waving in the air. He cannot hear a single sound. He has been completely deaf for years.

This is the story of how a man who could not hear a whisper created one of the most triumphant pieces of music in human history—a symphony that would later become the anthem of the European Union and a universal symbol of human solidarity.

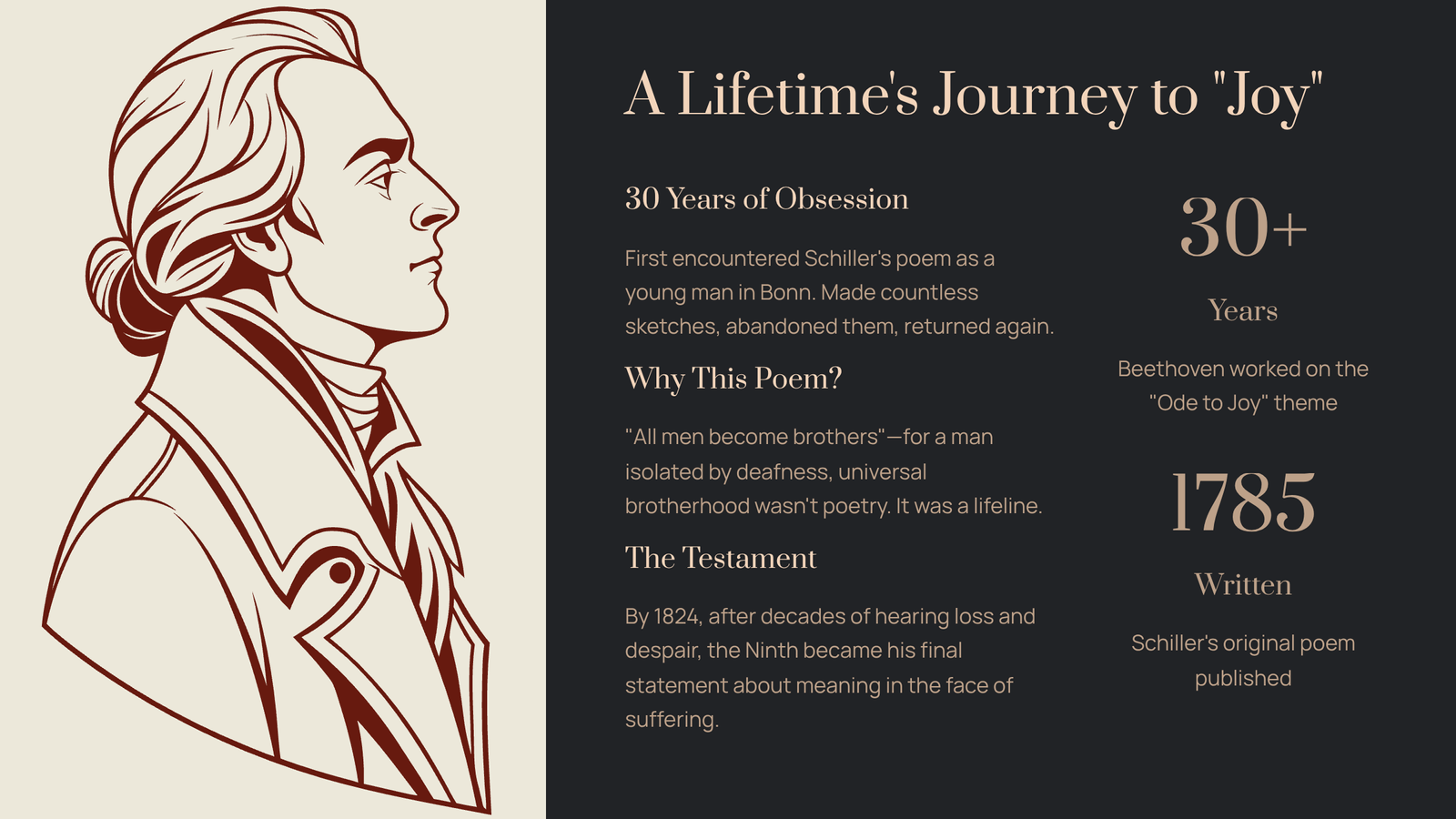

A Lifetime’s Journey to “Joy”

Beethoven didn’t simply wake up one morning and compose the Ninth Symphony. The “Ode to Joy” theme had been haunting him for over thirty years. As a young man in Bonn, he first encountered Friedrich Schiller’s poem “An die Freude” (Ode to Joy) and became obsessed with setting it to music. He made countless sketches, abandoned them, returned to them, abandoned them again.

Why did this particular poem captivate him so deeply? Written in 1785, Schiller’s ode celebrates the divine spark of joy that binds all humanity together—”All men become brothers, where your gentle wing rests.” For Beethoven, a man increasingly isolated by deafness, the vision of universal brotherhood wasn’t merely poetic. It was a lifeline.

By 1824, Beethoven had endured decades of progressive hearing loss, contemplated suicide, and emerged from despair with a renewed sense of purpose. The Ninth Symphony became his testament—a final statement about what music could mean, what life could mean, in the face of seemingly insurmountable suffering.

Breaking Every Rule in the Book

To understand why the Ninth Symphony was revolutionary, imagine the classical music world of 1824. Symphonies were instrumental works. Period. No one had ever placed a full choir and vocal soloists in a symphony before. Critics were scandalized. Traditionalists were appalled. Beethoven simply did not care.

The fourth movement begins not with the expected triumphant finale but with what musicians call the “Schreckensfanfare”—the fanfare of terror. Crashing dissonance. Chaos. It’s as if Beethoven is saying: before joy, we must confront suffering. The orchestra then reviews themes from the previous three movements, rejecting each one. Finally, the cellos and basses introduce the “Ode to Joy” melody—simple, almost childlike, like a folk tune anyone could hum.

Then comes the moment that electrified Vienna: the baritone soloist stands and sings, “O Freunde, nicht diese Töne!” (Oh friends, not these sounds!) It’s Beethoven speaking directly to us across two centuries. Let us raise our voices in more pleasant and joyful sounds.

How to Listen: Three Doorways into the Finale

First Listen: Follow the Melody’s Journey

The “Ode to Joy” theme appears first in the lowest strings, barely audible, almost tentative. It then passes through the entire orchestra like a rising tide—violas, violins, full orchestra with brass—each iteration gaining power and conviction. Track this progression from whisper to thunder. Notice how the same simple melody transforms through orchestration alone.

Second Listen: The Conversation Between Voices

Once the choir enters, listen for the interplay between soloists and chorus. The four vocal soloists—soprano, alto, tenor, bass—represent individual human voices, while the chorus embodies collective humanity. Watch how Beethoven weaves these textures together, sometimes in call-and-response, sometimes in overwhelming unison.

Third Listen: The Turkish March Surprise

Around the middle of the movement, everything suddenly changes. A tenor soloist sings with almost military energy, accompanied by percussion instruments associated with Turkish military bands—bass drum, cymbals, triangle. This “Turkish March” section was Beethoven’s nod to popular culture of his time. It’s energetic, almost playful. Let yourself smile.

Recordings That Reveal Different Truths

Wilhelm Furtwängler’s 1951 Bayreuth Festival recording captures something almost spiritual—the performance took place in the same theater where Wagner would later stage his operas, and the occasion marked Germany’s return to the international cultural community after World War II. The pacing is deliberate, the silences profound.

For a historically informed approach, John Eliot Gardiner’s recording with the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique uses period instruments and a leaner sound that reveals details often buried in modern orchestras. The tempos are quicker, closer to what Beethoven actually indicated.

Herbert von Karajan recorded the Ninth Symphony multiple times throughout his career. His 1962 Berlin Philharmonic recording offers that characteristic golden sound and architectural grandeur. It’s the version that shaped how generations heard Beethoven.

Carlos Kleiber’s 1996 live recording is volcanic, unpredictable, electric with the energy of live performance. If you want to feel what it might have been like in that Vienna theater in 1824, this comes closest.

Why It Still Matters

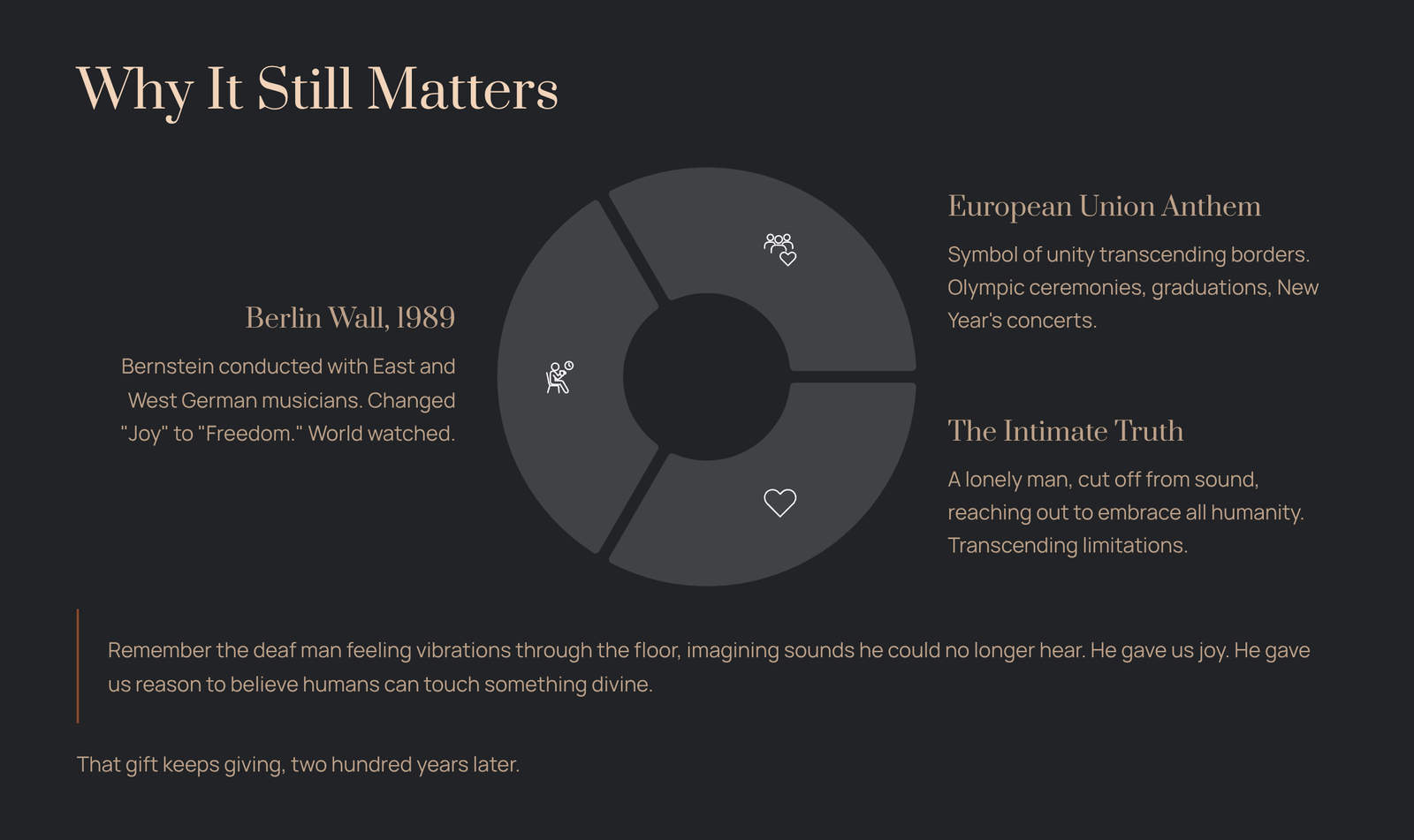

On November 9, 1989, as the Berlin Wall fell, Leonard Bernstein conducted the Ninth Symphony with musicians from both East and West Germany. He changed one word in Schiller’s text: instead of “Freude” (Joy), the chorus sang “Freiheit” (Freedom). The entire world watched.

The “Ode to Joy” melody has been adopted as the anthem of the European Union, a symbol of unity transcending national boundaries. It plays at Olympic ceremonies, New Year’s concerts, graduation celebrations. But these institutional uses can make us forget the intimate truth at the symphony’s heart: a profoundly lonely man, cut off from sound itself, reaching out to embrace all of humanity.

When you listen to the final minutes of the Ninth Symphony—the chorus building, the orchestra blazing, the tempo accelerating toward that last explosive chord—remember the deaf man standing with his back to the audience, feeling the vibrations through the floor, imagining the sounds he could no longer hear. He gave us joy. He gave us a reason to believe that human beings, despite everything, can transcend their limitations and touch something divine.

That gift keeps giving, two hundred years later.