Table of Contents

When a Heavenly Melody Reaches Across Time

Some music changes the air the moment you hear it. Your breathing shifts, and time seems to slow down in the most peculiar way. That’s what happened when I first encountered Gluck’s Mélodie. As the violin melody glided over the piano accompaniment, I suddenly felt transported—not to 18th-century Vienna exactly, but to a place beyond time and space where only sound exists.

This piece began life as an orchestral melody from the opera Orfeo ed Euridice—specifically, the “Dance of the Blessed Spirits.” Then, in the early 20th century, Viennese violinist and arranger Fritz Kreisler took this celestial tune and transformed it into an intimate gem for violin and piano. But he didn’t simply change the instrumentation. He breathed his own rhythm into every note, stretched fermatas just slightly, softened the legato even further, making the piece sound like a personal confession whispered across centuries.

Have you ever experienced a moment when you heard not someone’s voice, but their actual breath? That’s what this music felt like to me.

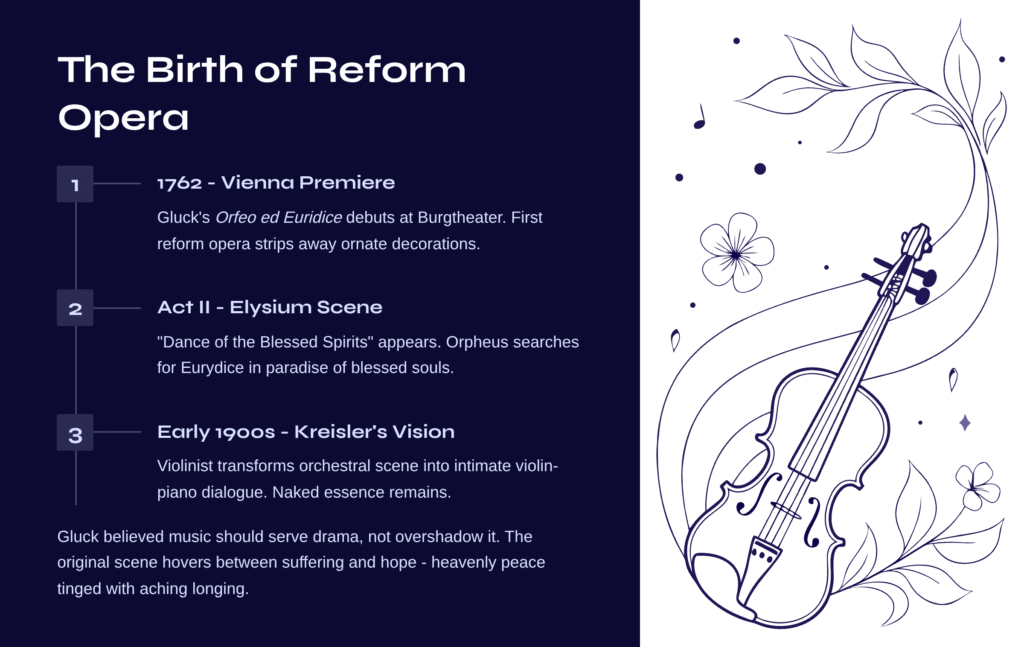

The Birth of Reform Opera and One Transcendent Scene

Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice premiered at Vienna’s Burgtheater in 1762. Opera of that era overflowed with ornate arias and virtuosic decorations, but Gluck took a different path. He believed music should serve the drama, not overshadow it. He stripped away unnecessary embellishments, leaving only emotional truth. This work became the first fruit of his “reform opera” vision.

The original “Dance of the Blessed Spirits”—which became Mélodie—appears in Act II. It’s the scene where Orpheus, searching for his beloved Eurydice, descends into the underworld. After passing through hell’s gates, he arrives at Elysium, the paradise where blessed souls dwell. The music that accompanies this moment hovers strangely between suffering and hope. It’s heavenly peace, yet tinged with aching longing.

Kreisler condensed this entire scene into one violin and one piano. The orchestra’s richness disappeared, but something more private and intimate took its place. It’s as if he peeled away the spectacle of the operatic stage, leaving only the melody’s naked essence.

How a Melody Breathes – Structure and Sonic Journey

This piece unfolds in a single movement lasting about three minutes. There’s nothing complicated about its form. Rather, delicacy shines through simplicity.

The violin sings the main melody from beginning to end. And I mean sings—each note flows seamlessly into the next, like a human voice. The melody begins in a high register, evoking celestial imagery, then descends to embrace human warmth. This rising and falling pattern repeats, and listeners find themselves surrendering to endless emotional waves.

The piano is the accompanist, yet never merely background. The left hand’s arpeggios flow beneath the melody like gentle ripples on water. The right hand responds—sometimes with chords, sometimes with brief melodic echoes—engaging in dialogue with the violin. It’s a wordless conversation. Not question and answer, but two voices breathing together, filling the same space.

Kreisler paid particular attention to legato and rubato. He introduced free tempo variations absent from the original, allowing the melody to flow as if liberated from time’s constraints. Certain phrases linger slightly, leaving resonance; others move naturally forward. These subtle tempo adjustments breathe life into the entire piece.

Resonance Found in Stillness

When I first heard this piece, I was doing nothing. Just sitting, gazing out the window in a sort of trance. But when the melody began, I lost awareness of where my eyes were looking. The sound entered me and touched something deep inside—something I can’t precisely name, but unmistakably real.

This music isn’t sad. But it isn’t happy either. It’s simply quiet. Yet within that quietness, every emotion dissolves and mingles. Longing, peace, hope, loss… all coexist within a single melodic line. As you listen, you realize you don’t need to define what you’re feeling. You just need to feel.

Perhaps this is the essence of Gluck’s “reform”—not brilliance or virtuosity, but pure emotional transmission. Kreisler understood this intention perfectly and created greater impact with smaller forces.

Listening to this piece, you too can discover your own quietness. Whether it’s longing, comfort, or simply a moment of pause.

How to Listen Deeper

First, focus on the violin’s breathing.

This piece is all about melody. Pay attention to how the violin begins and ends each phrase, the spacing between notes, the subtle nuances hidden in between. Listen as you would to someone speaking, noticing their particular way of expression.

Second, follow the piano’s resonance.

The piano accompaniment may seem simple, but pedaling completely transforms the atmosphere. Compare recordings that maintain clear, transparent resonance with those that choose warmer, more dreamlike textures. Daniel Lozakovich’s 2022 recording exemplifies the former approach.

Third, listen repeatedly.

This isn’t music you understand in one hearing. Each listen reveals new layers. First you hear only the melody, then the accompaniment’s flow, then the subtle dialogue between two instruments. I encourage you to take your time getting acquainted.

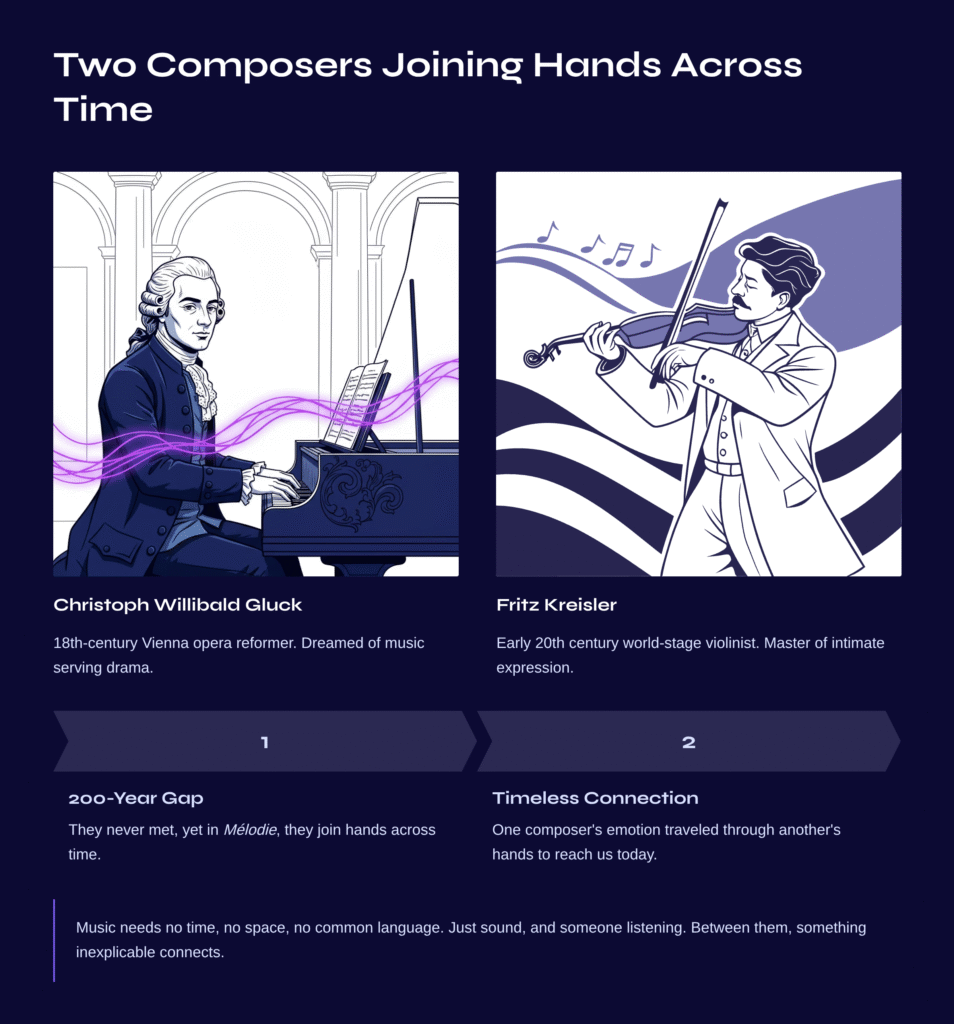

Afterglow – Two Composers Joining Hands Across Time

Gluck and Kreisler. One dreamed of opera reform in 18th-century Vienna; the other performed violin on world stages in the early 20th century. They never met, yet in Mélodie, they join hands.

Listening to this piece, I freshly understood what it means for music to transcend time. Across a 200-year gap, one composer’s emotion traveled through another composer’s hands to reach me in this moment. And someday it will reach you too.

That’s the magic of classical music. It needs no time, no space, no common language. Just sound, and someone listening. And between them, something inexplicable connects.

May this small melody place a quiet comma in your day.

The Next Journey – Ravel’s Portrait of a Young Princess

If Gluck’s celestial lyricism touched your heart, how about encountering a different texture of quietness? Maurice Ravel’s Pavane pour une infante défunte (Pavane for a Dead Princess). Despite its curious title, this isn’t actually a lament for a deceased princess. As Ravel himself explained, it’s simply a pavane he imagined “a little princess might have danced in the old Spanish court.”

Originally written for solo piano, this work handles time differently than Gluck’s Mélodie. Where Gluck’s music flows with celestial spirits, Ravel’s recalls a past already gone. Above a slow, graceful dance rhythm, the melody unfolds note by careful note, evoking the sensation of gazing at an antique portrait.

The journey from Gluck to Ravel moves from lyrical meditation to retrospective melancholy. Neither piece is flashy, yet the emotional depth contained within surpasses many grander works. Listening to Ravel’s pavane, you’ll discover your own story within yet another kind of stillness.