Table of Contents

An Afternoon, A Dance That Doesn’t Dance

Some music stops time the moment you hear it. Handel’s Sarabande does exactly that. The melody flowing over a slow triple meter is a dance that doesn’t invite you to dance. Rather, it whispers: stop, bow your head right there, and listen.

When I first heard this piece, I simply thought it was “beautiful.” But after listening two, three times, I began to feel the weight hidden behind that beauty. This wasn’t just a simple dance. It was a portrait painted in sound, using the steps of a Baroque court dance to depict both human solitude and dignity simultaneously.

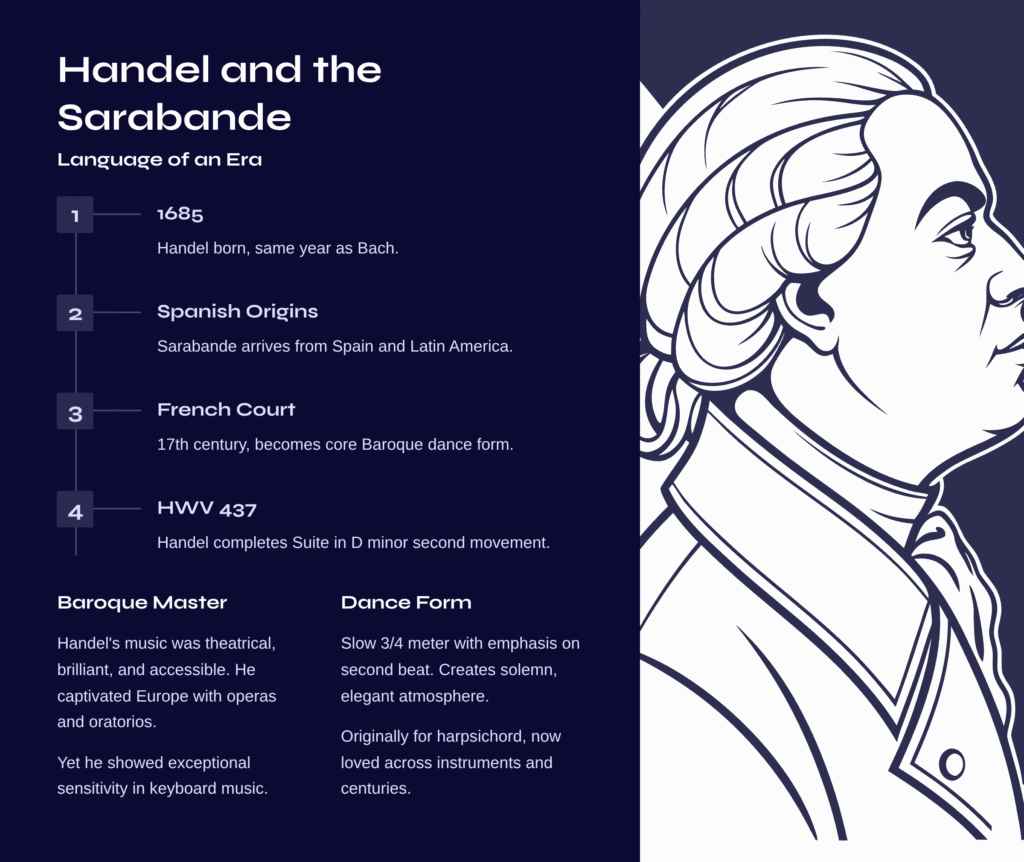

Handel and the Sarabande, Language of an Era

George Frideric Handel (1685–1759) was a master of the Baroque era. Born in the same year as Bach, his music was more theatrical, more brilliant, more accessible to the public. Though he captivated all of Europe with his operas and oratorios, he also demonstrated exceptional sensitivity in keyboard music.

The Sarabande originally came from Spain and Latin America, and after passing through the French court in the 17th century, established itself as a core Baroque dance form. Characterized by a slow 3/4 meter with emphasis on the second beat, it creates a solemn and elegant atmosphere. Handel reinterpreted this form in his own way, completing it as the second movement of his Keyboard Suite in D minor, HWV 437.

This piece was originally composed for harpsichord, but has since been performed and loved across centuries in piano, string ensemble, and even orchestral arrangements. Each time the instrument changes, so does the piece’s expression. That’s precisely the charm of this music.

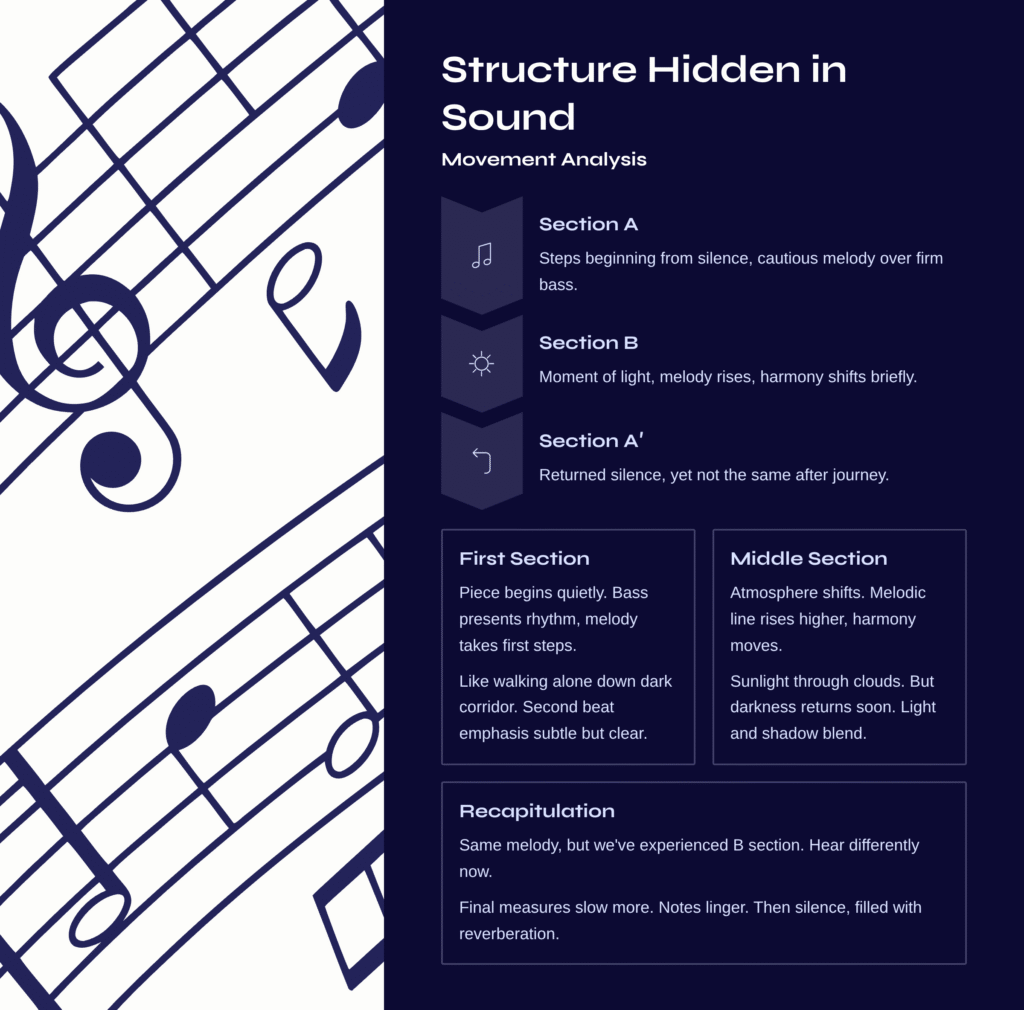

Structure Hidden in Sound – Movement Analysis

Handel’s Sarabande appears simple on the surface, but looking inside reveals an intricately woven musical structure. It follows an overall A–B–A′ form, with restrained melody unfolding over a repeating bass pattern.

First Section (A): Steps Beginning from Silence

The piece begins very quietly. The bass slowly but firmly presents the rhythm, and above it the right-hand melody cautiously takes its first steps. It feels like someone walking alone down a dark corridor.

The emphasis on the second beat is subtle but clear. At each such moment, the music breathes. This breathing governs the entire piece. Ornaments appear sparsely, but never excessively. Rather, that restraint evokes deeper emotion.

Middle Section (B): A Moment of Light, Then Shadow

Moving into the B section, the atmosphere shifts slightly. The melodic line rises a bit higher, and the harmony moves. Like sunlight filtering through clouds. But that light doesn’t last long. Darkness returns soon after.

This is where performers’ interpretations diverge. Some create dramatic contrast, others let it flow naturally. I prefer the latter. When light and shadow blend, when that boundary becomes blurred, I feel emotions closer to truth.

Recapitulation (A′): Returned Silence, Yet Not the Same

We return to A, but this time it’s different from the beginning. The same melody, but we’ve already experienced B. That experience makes us hear the music differently. As we approach the final measures, the tempo slows even more, and the notes linger longer.

And then the final chord. After it fades, only silence remains. But that silence isn’t empty. The reverberation of every sound we just heard remains within it.

My Own Interpretation – A Solo Dance

Every time I listen to this piece, I imagine someone dancing alone. In a ballroom but without a partner, the music slow, and that person simply dancing with themselves. It seems sad, yet also free.

This piece is lonely but not isolated. Do you understand the difference? Loneliness is missing someone, but isolation is being with oneself. Handel’s Sarabande leans toward the latter.

The texture of this emotion changes with each performance version. Heard on harpsichord, it sounds cool and clear; on piano, warm and profound. With orchestra, individual emotion expands into collective narrative. The same piece, yet offering entirely different experiences.

Three Tips for Deep Listening

1. Focus on the Second Beat

The essence of the Sarabande lies in the second beat. That’s where the music breathes. Listen carefully to how the performer handles that moment. Some give it strong accent, others emphasize it softly. That difference completely changes the piece’s character.

2. Compare Across Instruments

Listen in sequence to harpsichord versions (Trevor Pinnock, Gustav Leonhardt), piano version (Martha Argerich), and orchestral version (Academy of Ancient Music). You’ll be amazed that such different colors can emerge from the same score. Which version draws you more? That answer reveals your musical taste.

3. Listen Repeatedly, Slowly

This isn’t music you can understand in one listening. The more you listen—twice, three times—the more new things you hear. A bass line you didn’t hear yesterday becomes audible today, and the trembling of ornaments you didn’t feel today will be felt tomorrow. Let’s not rush. Not the music, not ourselves.

A Dance Beyond Time

Handel’s Sarabande is a 300-year-old score, yet listening to it now feels anything but strange. No, rather it sounds more urgent precisely because we’re hearing it now. In a fast-spinning world, this piece says: stop. Walk slowly, feel your own breathing, discover yourself within that rhythm.

Even after the music ends, the resonance remains. That is the power of this piece. Music that transcends time, staying by your side in this very moment. Handel’s Sarabande is such a piece.

A Suggestion for the Next Journey – Rachmaninoff’s Vocalise

If you’ve fully savored Handel’s restrained beauty, it’s time to encounter music that makes you forget time in an entirely different way. Sergei Rachmaninoff’s Vocalise (Op. 34 No. 14) is a vocal piece sung without lyrics, using only the voice, but it’s also widely beloved in instrumental arrangements.

If Handel restrained emotion within the Baroque dance form, Rachmaninoff unfolds emotion endlessly through the language of late Romanticism. The Vocalise carries longing and melancholy that cannot be expressed in words, over a melody that flows like a long sigh. Heard in cello or violin versions, that resonance penetrates deep into the heart.

If Handel’s Sarabande was “a solo dance,” Rachmaninoff’s Vocalise is “a wordless confession.” Both demonstrate the power of music beyond language. The journey from Handel to Rachmaninoff will let you experience a spectrum of emotion moving from Baroque to Romanticism, from restraint to expansion.

Next time, let’s enter together into the world of this Vocalise. You’ll be amazed once again at how much can be said without words.