📑 Table of Contents

Picture this: Paris, April 1832. A charity concert for cholera victims fills the Opera house. On stage stands a gaunt, almost skeletal figure with impossibly long fingers—Niccolò Paganini, the violinist rumored to have sold his soul to the devil. In the audience sits a 19-year-old Hungarian pianist named Franz Liszt, and he’s about to have his entire world shattered.

After the concert, Liszt wrote to a friend with trembling conviction: “What a man, what a violin, what an artist! Heavens, how much suffering, misery, and torture in those four strings!” That night, something broke inside him—or perhaps something finally clicked into place. Within days, he began practicing scales for four to five hours daily. Sometimes fourteen. He was no longer content to be merely talented. He wanted to become the Paganini of the piano.

La Campanella is the sonic evidence of that obsession.

The Transformation of Obsession

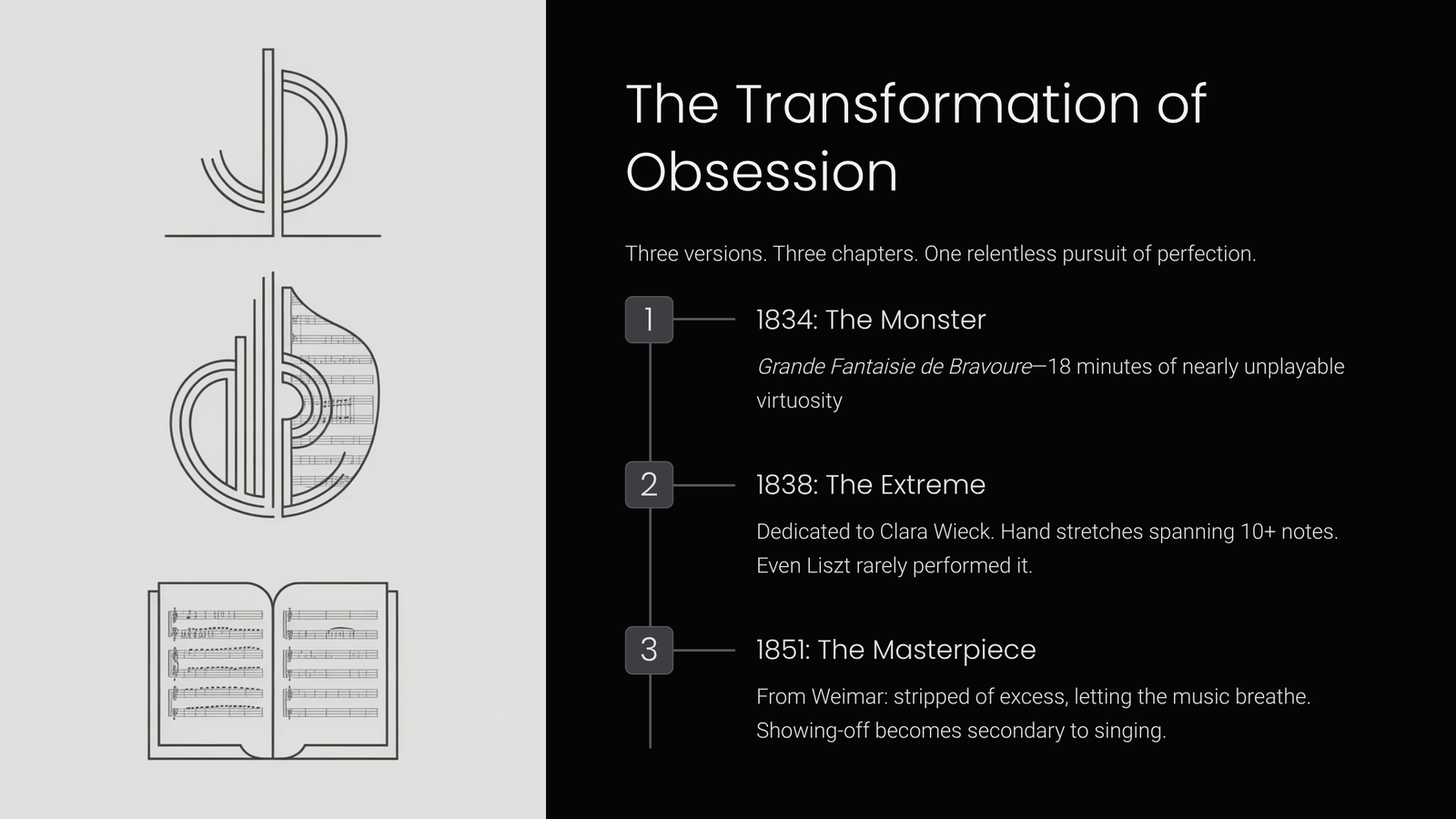

The piece you hear today didn’t spring fully formed from Liszt’s imagination. It evolved through three distinct versions, each marking a chapter in his artistic journey.

First came the sprawling Grande Fantaisie de Bravoure sur La Clochette around 1834—an 18-minute monster of a fantasy that took Paganini’s original violin melody and exploded it into something almost unplayable. Then came the 1838 version, published as part of his Études d’exécution transcendante d’après Paganini, dedicated to the young Clara Wieck (later Clara Schumann). This version was so brutally difficult, with hand stretches spanning more than ten notes, that even Liszt himself rarely performed it.

The final 1851 revision is what we know today. By then, Liszt had settled in Weimar, transforming from touring virtuoso to contemplative composer. He stripped away the most extreme technical demands—not to make it easy (it remains one of the most challenging pieces in the repertoire), but to let the music breathe. The showing-off became secondary to the singing.

What Does “La Campanella” Actually Mean?

The title translates simply as “The Little Bell,” but there’s nothing simple about its origins. Paganini’s original came from the finale of his Second Violin Concerto, where he actually rang a small bell on stage to announce each return of the main theme. The melody itself echoes an old Italian folk tune, and Paganini used violin harmonics—those ethereal, whistling tones produced by barely touching the strings—to imitate the bell’s crystalline ring.

Liszt faced an interesting problem: how do you make a piano ring like a bell? His solution was ingenious. He placed the melody in the instrument’s highest register, using rapid repeated notes and enormous leaps to create that shimmering, almost otherworldly quality. When played well, the piano doesn’t sound like a piano anymore. It transforms into something suspended between instrument and idea.

A Roadmap for Your Ears

If you’ve never listened to La Campanella with intention, here’s what to notice:

The Opening Shimmer (0:00–0:30)

Those first high notes aren’t just introduction—they’re the bell itself, ringing from some distant tower. Notice how they seem to hover in the air, not quite landing anywhere. The pianist’s challenge here isn’t volume but touch: making each repeated note distinct yet connected, like echoes bouncing off stone walls.

The Melody Emerges (0:30–1:20)

Beneath the bells, a simple, almost naive tune appears. It’s surprisingly humble for such a technically demanding piece—a lilting dance that could belong to an Italian countryside. The left hand provides gentle support while the right hand stretches across impossible distances. Watch for those leaps: sometimes the pianist’s hand must travel more than an octave in a fraction of a second.

The Variations Begin (1:20–3:30)

Like a theme-and-variations form, Liszt takes that innocent melody and progressively ornaments it. Each repetition adds new challenges: faster passages, more complex harmonies, double notes that require two fingers to strike simultaneously at breakneck speed. The bell motif keeps returning, anchoring us to the original image even as the music grows increasingly elaborate.

The Storm (3:30–4:00)

Here’s where pianists earn their reputation—or lose it. The climax unleashes cascading octaves, the most technically brutal passage in the entire piece. The dynamic swells to fortissimo while the tempo pushes toward human limits. Everything Liszt learned from watching Paganini’s fingers fly across four strings, he compressed into these thirty seconds.

The Return (4:00–end)

After the storm, the bells return, softer now. The melody reappears in a simplified form, as if seen through memory. The piece doesn’t so much end as fade, like a bell’s vibration slowly dying into silence.

Why Clara Schumann Hated It (Sort Of)

There’s a delicious irony in Liszt dedicating both versions to Clara Schumann. She was one of the finest pianists of her era, and she certainly respected his technical abilities. But she couldn’t stand his music.

In her diary, she wrote that attending his concerts felt like watching someone drink and shout rather than make music. She found his compositions chaotic, his style excessive. Yet Liszt kept dedicating works to her—perhaps as a gesture of genuine admiration for her playing, perhaps as an elaborate tease.

Their relationship captures something essential about La Campanella itself: it lives at the intersection of spectacle and substance, showing off and genuine musical expression. You can dismiss it as circus tricks, or you can hear in it something almost spiritual—a young man’s desperate attempt to transcend the limits of what fingers can do.

Recordings Worth Your Time

György Cziffra offers perhaps the most dazzling technical display. His fingers seem to operate outside normal physics, producing a crystalline clarity that makes every note sparkle. If you want to understand why this piece terrifies pianists, watch Cziffra make it look effortless.

Vladimir Horowitz takes a more dramatic approach, playing with the tempo and dynamics in ways that some purists find excessive. But there’s an undeniable electricity in his performances—you can feel him pushing against the boundaries of the composition itself.

For a more recent interpretation, Yuja Wang brings both technical precision and emotional depth, reminding us that behind all the fireworks lies an actual piece of music with something to say.

The Devil’s Shadow

We can’t talk about La Campanella without mentioning its supernatural undertones. Paganini was widely believed to have made a deal with Satan—how else could anyone play like that? The Catholic Church refused to bury his body for years after his death. When Liszt channeled Paganini’s spirit into the piano, some of that diabolical reputation came with it.

There’s something almost occult about watching a great pianist perform this piece: the impossible leaps, the superhuman speed, the way the music seems to demand more than ten fingers can reasonably provide. Liszt wasn’t just transcribing Paganini’s notes. He was trying to capture the sense of witnessing something that shouldn’t be possible.

What This Piece Asks of You

La Campanella rewards active listening. Don’t put it on as background music—it will either annoy you with its insistence or fade into wallpaper, both of which waste what makes it special.

Instead, try this: find five minutes of genuine attention. Put on headphones if you can. Close your eyes during that opening shimmer and try to actually hear bells. Follow the melody as it twists through its variations. Feel the tension build during the climactic octaves. Then let the final fading notes return you to wherever you started, changed in some small way.

That’s what Liszt experienced watching Paganini in 1832—a transformation through pure sound. Almost two centuries later, La Campanella still carries that transformative charge, waiting for anyone willing to truly listen.

The little bell keeps ringing. It’s been ringing since that April night in Paris when a young man decided that being talented wasn’t enough, that he wanted to touch the divine—or the diabolical—through his instrument. Every pianist who attempts this piece, every listener who surrenders to its demands, becomes part of that ongoing story.

The question is: will you answer the bell?