📑 Table of Contents

- The Man Behind the Musical Revolution

- From Pushkin’s Pen to Glinka’s Score

- What You’re Actually Hearing

- The Whole-Tone Revolution

- Why Double Bassists Have Nightmares

- The Strange Fate of Opera vs. Overture

- Where You’ve Definitely Heard This Before

- How to Listen: A Personal Guide

- Recommended Recordings

- The Legacy That Launched a Thousand Ships

- Five Minutes That Changed Everything

Some mornings, you don’t need another espresso shot. You need five minutes of pure, unadulterated musical adrenaline coursing through your veins. Enter Mikhail Glinka’s Ruslan and Lyudmila Overture—a piece so electrifying that it’s been waking people up since 1842.

But here’s the twist: this isn’t just any orchestral showpiece. This is the piece that single-handedly gave birth to Russian classical music as we know it. Every Russian composer who came after—Tchaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, Mussorgsky—owes a debt to this five-minute whirlwind. And legend has it, Glinka wrote it in just 24 hours.

The Man Behind the Musical Revolution

Mikhail Glinka wasn’t your typical tortured artist. Born into Russian nobility in 1804, he spent his childhood wrapped in his grandmother’s overprotective embrace—literally kept in rooms heated to 25°C like a delicate houseplant. This coddled upbringing left him with lifelong health anxieties, but it didn’t stop him from becoming the father of Russian national music.

By the late 1830s, Glinka had already tasted success with his first opera A Life for the Tsar. He held a prestigious position as director of the Imperial Chapel Choir, earning a comfortable 25,000 rubles annually with palace accommodations included. Life should have been good.

It wasn’t.

His marriage to Maria Petrovna Ivanova was a disaster. She cared nothing for music, spent money recklessly, and eventually, her infidelities came to light. In 1839, amid emotional turmoil and a new forbidden romance with Ekaterina Kern (daughter of Pushkin’s former flame), Glinka threw himself into composing his second opera.

From Pushkin’s Pen to Glinka’s Score

The source material was Alexander Pushkin’s 1820 narrative poem Ruslan and Lyudmila—a playful, fantastical tale set in medieval Kiev. The story follows the knight Ruslan on a quest to rescue his bride Lyudmila, kidnapped by the evil dwarf-sorcerer Chernomor on their wedding night. Think Russian folklore meets Arthurian romance with a dash of magical mischief.

Pushkin himself had planned to write the opera’s libretto. That dream died with him in 1837, killed in a duel at age 37. The final libretto became a patchwork effort—one poet allegedly sketched the basic plot in 15 minutes while drunk. The result? Magnificent music trapped in a dramatically messy opera.

But the overture? The overture is perfection.

What You’re Actually Hearing

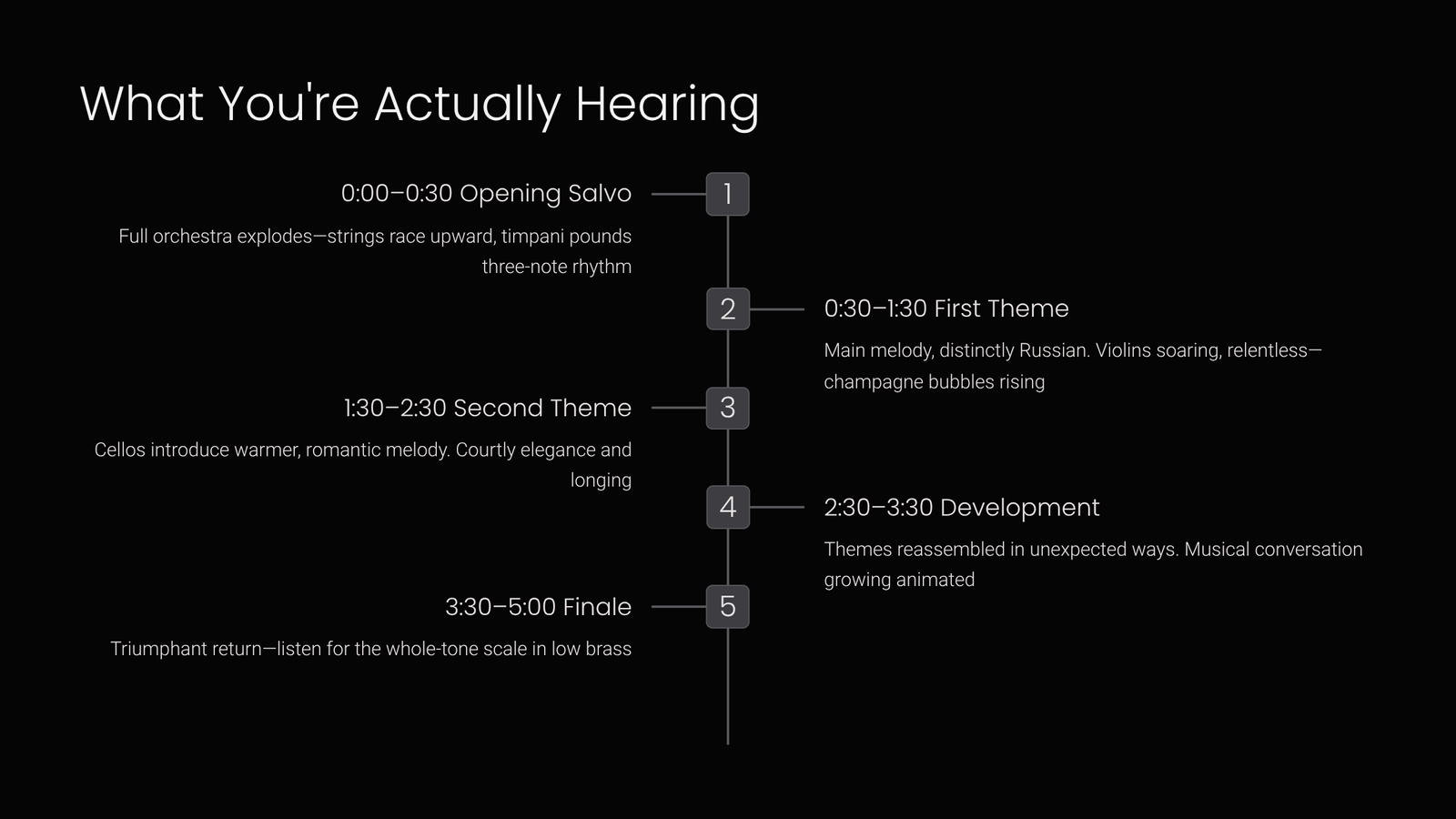

The moment you press play, there’s no warning. The full orchestra explodes into action—a sonic declaration of intent that grabs you by the collar and refuses to let go. This isn’t music that eases you in; it announces itself like a knight charging into battle.

The Opening Salvo (0:00–0:30): The piece begins with what musicians call an “assertive motto”—a bold orchestral statement that sets the tempo for everything to come. Strings race upward like horses at full gallop while the timpani pounds out a three-note rhythm that becomes the heartbeat of the entire work.

The First Theme (0:30–1:30): Here comes the main melody, distinctly Russian in character. The violins carry it—bright, soaring, absolutely relentless. This theme originated from a festive chorus in Act 1 of the opera, and you can hear the celebration in every note. It’s the musical equivalent of champagne bubbles rising in a glass.

The Second Theme (1:30–2:30): Now the mood shifts. The cellos introduce a warmer, more romantic melody—this one borrowed from Ruslan’s love aria in Act 2. Where the first theme was all heroic energy, this one breathes with courtly elegance and romantic longing. Listen for the deeper instruments (violas, bassoons) painting the emotional landscape.

The Development (2:30–3:30): Glinka takes both themes apart and reassembles them in unexpected ways. The music travels through distant keys, building tension. Fragments of melody pass between instrument groups like a musical conversation growing increasingly animated. There’s a playful quality here, as if the orchestra itself is enjoying the game.

The Recapitulation and Finale (3:30–5:00): Both themes return in triumphant form, but Glinka saves his most innovative touch for the very end. Listen carefully to the low brass and bassoons in the final moments—they play a descending whole-tone scale, a harmonic device so unusual for 1842 that Russian musicians still call it “Chernomor’s Scale” after the opera’s villain.

The Whole-Tone Revolution

That strange, otherworldly scale in the coda deserves special attention. In 1842, the whole-tone scale was essentially uncharted territory in Western music. This six-note scale, with equal intervals between each note, creates a floating, ambiguous sensation—neither happy nor sad, neither resolved nor tense. It simply… hovers.

Glinka used it to evoke Chernomor’s dark magic, and in doing so, he planted a seed that wouldn’t fully bloom until Claude Debussy explored whole-tone harmonies sixty years later. Every time you hear that eerie, dreamlike quality in Impressionist music, remember: Glinka got there first.

Why Double Bassists Have Nightmares

Here’s a piece of orchestral gossip: among professional musicians, this overture is infamous. Specifically, it’s notorious for being what one critic called “a nightmare for double bassists.”

The string parts move at breakneck speed with minimal rest. The low strings must execute rapid-fire passages with perfect intonation while the entire orchestra barrels forward like a runaway train. Orchestra auditions frequently include excerpts from this overture precisely because it separates the prepared from the panicked.

The Strange Fate of Opera vs. Overture

When Ruslan and Lyudmila premiered on November 27, 1842, at the Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre in St. Petersburg, the reception was lukewarm at best. The Russian audience, enamored with Italian opera, didn’t quite know what to make of this homegrown creation. Tsar Nicholas I actually established an Italian opera company in the same theater the following year, effectively sidelining Russian opera.

Glinka was devastated. He spent the following year in deep melancholy.

But here’s the irony: while the full opera struggled to find its audience (it wasn’t performed in America until 1977!), the overture immediately became a concert hall favorite. Today, you might go your entire life without seeing Ruslan and Lyudmila staged, but you’ve almost certainly heard its overture somewhere.

Where You’ve Definitely Heard This Before

If the melody sounds oddly familiar, you might be a fan of American sitcoms. Chuck Lorre—the producer behind The Big Bang Theory and Young Sheldon—chose this overture as the theme song for the CBS series Mom (2013–2021). For eight seasons, roughly 12 million viewers weekly heard Glinka’s masterpiece announcing another episode about addiction recovery and family dysfunction.

The choice wasn’t random. According to the show’s music consultant, cellist Michael Goldschlager, the overture captures both “gravitas” and “urgency”—weighty classical credibility paired with the manic energy of modern life. It’s a surprisingly perfect match.

The piece has also appeared in BBC Radio 4’s comedy Cabin Pressure and the children’s animated series Oscar’s Orchestra, where it served as the musical standard-bearer for a resistance movement against a music-banning dictator.

How to Listen: A Personal Guide

For your first listen, I recommend doing absolutely nothing else. Not checking your phone. Not reading. Not even following along with this guide. Just let the music hit you like a wave.

On subsequent listens, try these approaches:

For pure energy: Use it as your morning alarm or pre-workout anthem. The relentless forward momentum is physiologically impossible to ignore.

For musical details: Follow the timpani throughout. That three-note pattern is your anchor—notice how Glinka uses it to maintain unity even when everything else is changing.

For emotional depth: Pay attention to the second theme’s appearances. Each time it returns, notice how the orchestration changes, how different instruments color the same melody with new shades of feeling.

Recommended Recordings

For historical authenticity: Yevgeny Mravinsky conducting the Leningrad Philharmonic (1962 Budapest live recording). This is Russian musicians playing Russian music with an intensity born of lived tradition. The tempo is ferocious.

For audio quality: David Zinman with the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra. Crystal-clear modern recording that lets you hear every instrumental detail.

For sheer orchestral glamour: Georg Solti with the London Symphony Orchestra (1966). Big, bold, and unapologetically spectacular.

The Legacy That Launched a Thousand Ships

When Vladimir Stasov, the influential Russian music critic, declared that “Russian musical culture would not have developed without Ruslan and Lyudmila,” he wasn’t exaggerating. This opera—and particularly this overture—established the template that “The Mighty Five” (Balakirev, Borodin, Cui, Mussorgsky, and Rimsky-Korsakov) would spend the next half-century expanding.

Glinka’s innovations weren’t just harmonic. His orchestration technique—what scholars call the “changing background” method, where the same melody returns with completely different instrumental colors—became a cornerstone of Russian compositional style. When you hear Rimsky-Korsakov’s glittering orchestrations or Tchaikovsky’s lush instrumental combinations, you’re hearing Glinka’s DNA.

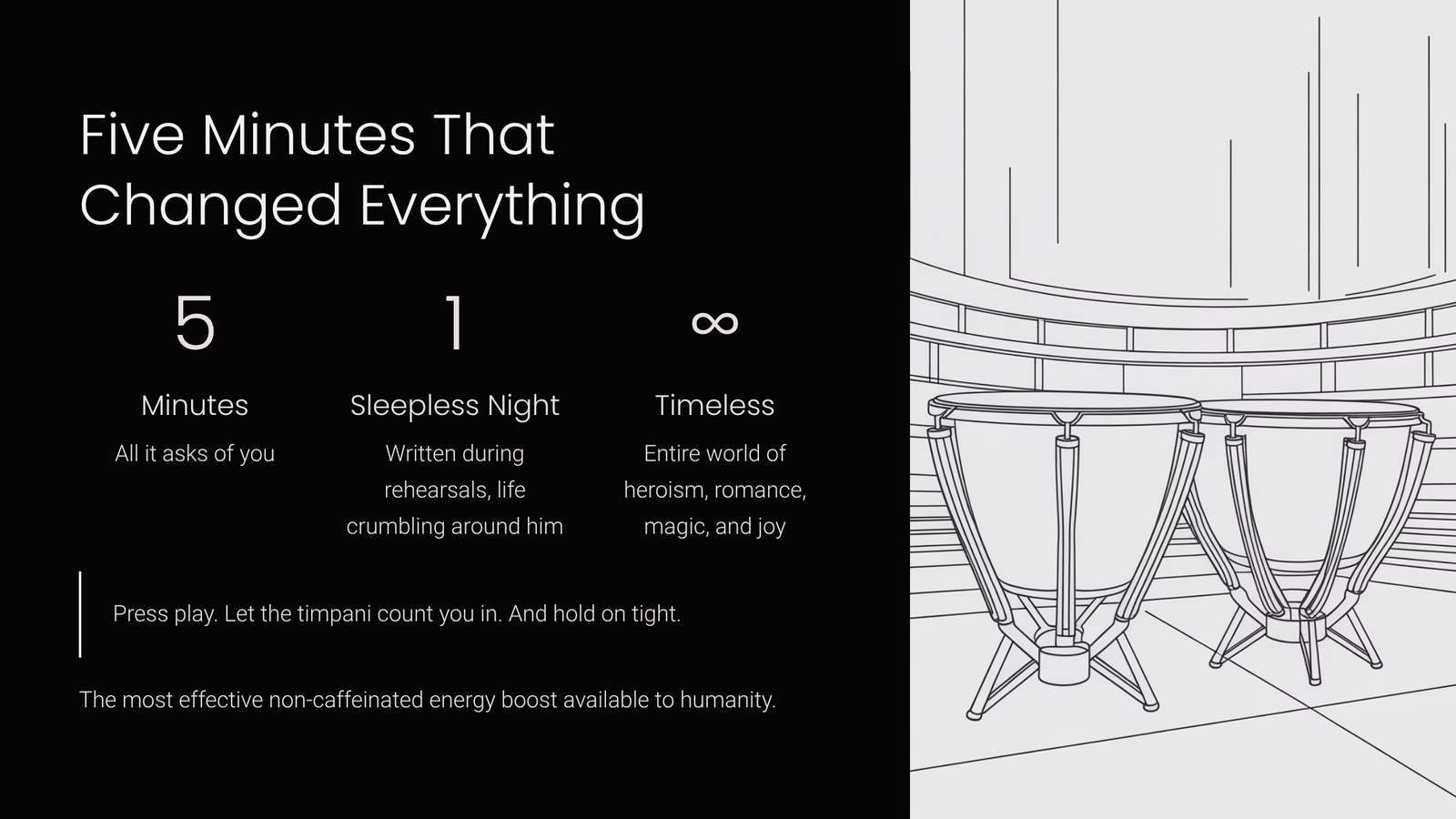

Five Minutes That Changed Everything

The Ruslan and Lyudmila Overture asks almost nothing of you. Five minutes. An open pair of ears. Maybe a willingness to let your pulse quicken and your spirits lift despite your better judgment.

What it offers in return is extraordinary: a window into the birth of a national musical identity, a demonstration of pure orchestral virtuosity, and—if you need it—the most effective non-caffeinated energy boost available to humanity.

Glinka may have written it in a single sleepless night during rehearsals. He certainly composed it while his personal life crumbled around him. But what emerged from that chaos was something timeless: proof that five minutes of music can contain an entire world of heroism, romance, magic, and joy.

Press play. Let the timpani count you in. And hold on tight.