📑 Table of Contents

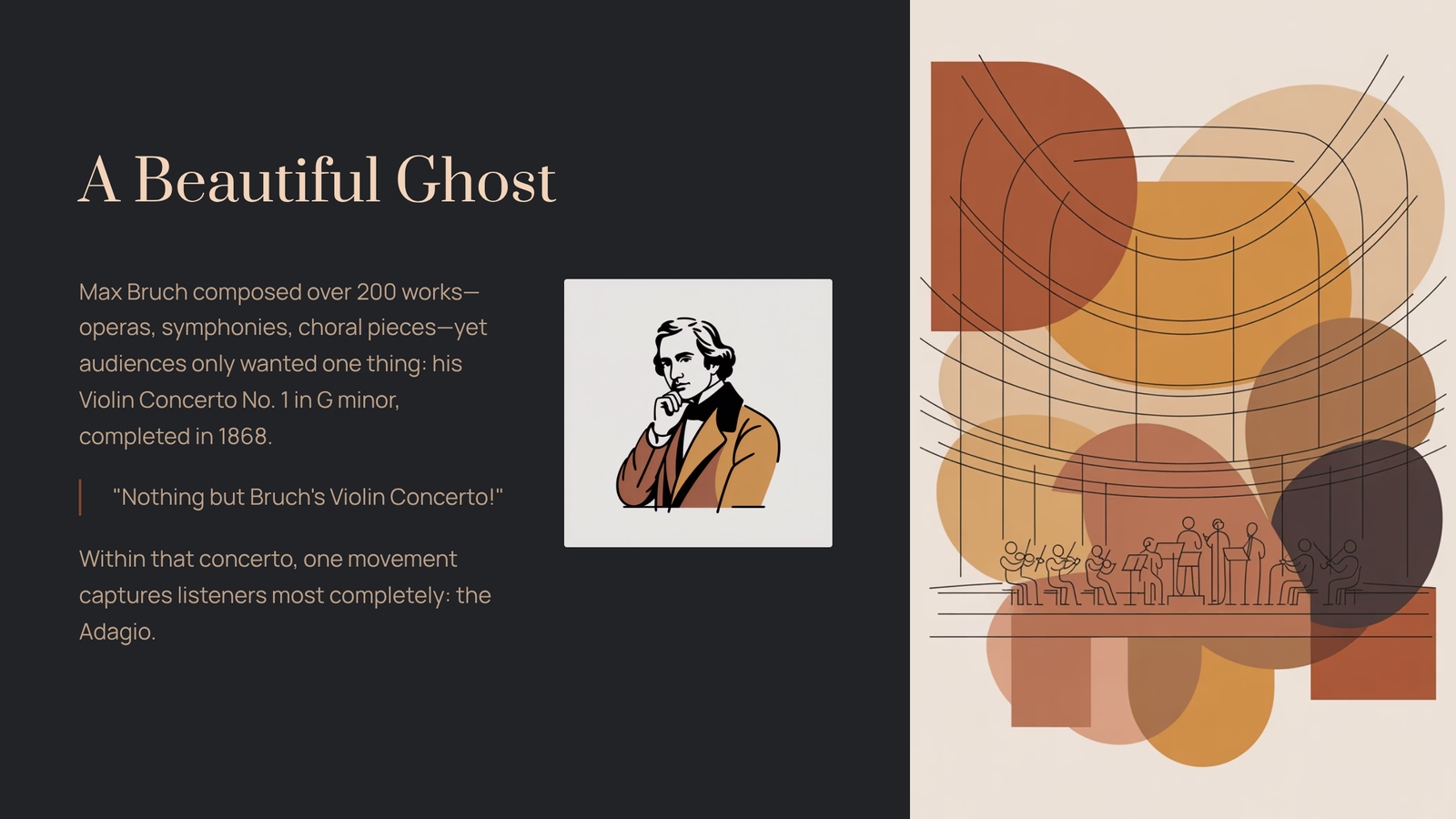

Max Bruch had a problem most artists would envy: he wrote something so perfect, so achingly human, that it eclipsed everything else he ever created. His Violin Concerto No. 1 in G minor, completed in 1868, would follow him like a beautiful ghost for the rest of his life.

“Nothing but Bruch’s Violin Concerto!” he reportedly complained in his later years. He composed over 200 works—operas, symphonies, choral pieces—yet audiences only wanted to hear one thing. And within that concerto, one movement captures listeners most completely: the second movement, the Adagio.

If you’ve ever felt an emotion too vast to name, too tender to speak aloud, this is its soundtrack.

The Story Behind the Adagio

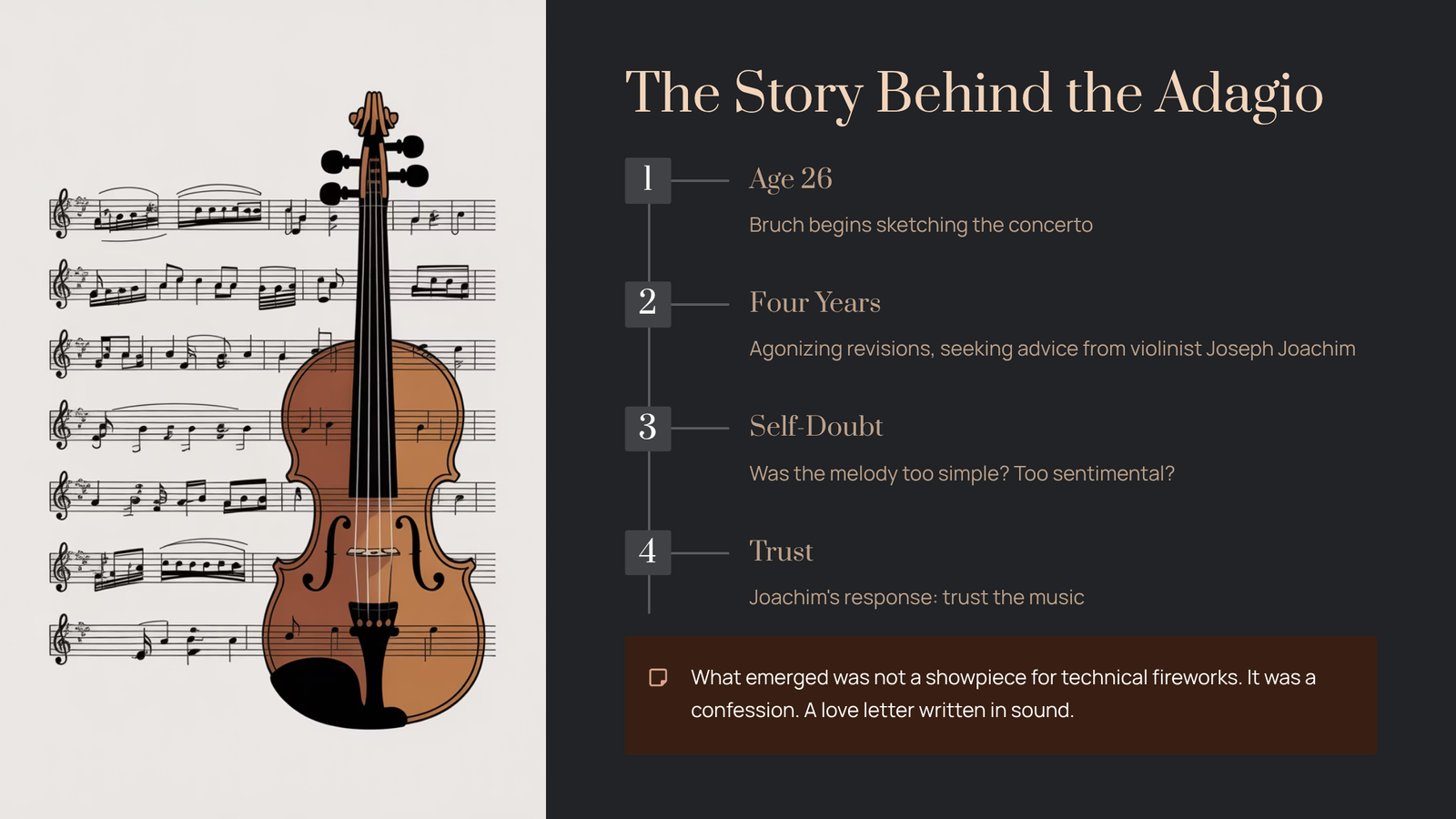

Bruch was just 26 years old when he began sketching this concerto, and he spent four agonizing years revising it. He sought advice from the legendary violinist Joseph Joachim, sending draft after draft, questioning every phrase. Was the melody too simple? Too sentimental? Not virtuosic enough?

Joachim’s response was essentially: trust the music.

The Adagio that emerged from this uncertainty is anything but uncertain. It opens with the orchestra establishing a warm, enveloping harmonic bed—like arms opening to receive you. Then the solo violin enters, and time seems to suspend.

What Bruch created was not a showpiece for technical fireworks. It was a confession. A love letter written in sound.

Why This Movement Speaks to Everyone

Here’s what makes the Adagio remarkable: it requires no musical training to understand. You don’t need to know what “E-flat major” means or why the modulation to C minor matters. Your body already knows.

The melody rises and falls like breathing. It pushes toward moments of intensity, then retreats into quietude. There are passages where the violin seems to be asking a question—and passages where it simply weeps.

Some listeners hear romantic love in these notes. Others hear grief, or spiritual yearning, or the bittersweet ache of memory. Bruch never specified what the Adagio “means.” Perhaps he understood that its power lies precisely in this ambiguity.

How to Listen: Three Doorways Into the Music

First listen: Complete surrender. Don’t analyze. Don’t multitask. Find a quiet space, close your eyes, and let the music wash over you. Notice where your breath catches. Notice if your chest tightens or your eyes grow warm.

Second listen: Follow the conversation. The violin and orchestra aren’t just playing together—they’re speaking to each other. Listen for moments when the orchestra swells beneath the soloist, offering support. Notice when the violin climbs to its highest register, as if reaching for something just out of grasp.

Third listen: Find the architecture. The movement follows a loose ABA structure. The opening theme returns near the end, but transformed—deeper, more resigned. It’s the same melody, yet somehow it carries the weight of everything that happened in between.

Recommended Recordings to Start With

Jascha Heifetz (1951) – The gold standard for many. Heifetz plays with aristocratic restraint, letting the melody speak without excessive vibrato. Some find it cool; others find it devastatingly elegant.

Anne-Sophie Mutter (1980) – Recorded when she was just 17, with Karajan conducting. Her interpretation is warmer, more openly emotional. The Berlin Philharmonic provides lush, almost symphonic support.

Hilary Hahn (2019) – A modern touchstone. Hahn’s tone is crystalline, her phrasing thoughtful. If you’re new to classical violin, this recording is wonderfully accessible.

Itzhak Perlman – For sheer warmth and generosity of sound, Perlman is hard to surpass. His vibrato is rich without being cloying.

Each violinist reveals different facets of the same gem. There’s no “correct” interpretation—only the one that speaks to you.

The Paradox of Simple Beauty

In an era when many composers were pushing toward greater complexity, Bruch did something quietly radical: he trusted melody. He trusted emotion. He trusted that listeners didn’t need to be impressed—they needed to be moved.

The Adagio from his First Violin Concerto has been played at weddings and funerals, in concert halls and hospital rooms. It has accompanied first loves and final goodbyes. Its simplicity is not a limitation. It is a doorway wide enough for anyone to enter.

Bruch may have resented being remembered for only one work. But perhaps he was looking at it wrong. To create something that speaks to millions of people, across cultures and centuries—that isn’t a small achievement. That is everything.

Listen once. Let it find you where you are.