📑 Table of Contents

Some music is simply too alive to be buried inside a larger work. In 1863, Camille Saint-Saëns composed what he intended to be the finale of his First Violin Concerto. But when Spanish virtuoso Pablo de Sarasate premiered it in Paris four years later, something unexpected happened: the finale stole the show so completely that Saint-Saëns had no choice but to set it free.

That rebellious finale became the Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso, Op. 28—a nine-minute journey from melancholy whispers to Spanish fire that has captivated audiences for over 150 years. If you’ve ever wanted to understand why violin virtuosos exist, this piece is your answer.

The Friendship Behind the Music

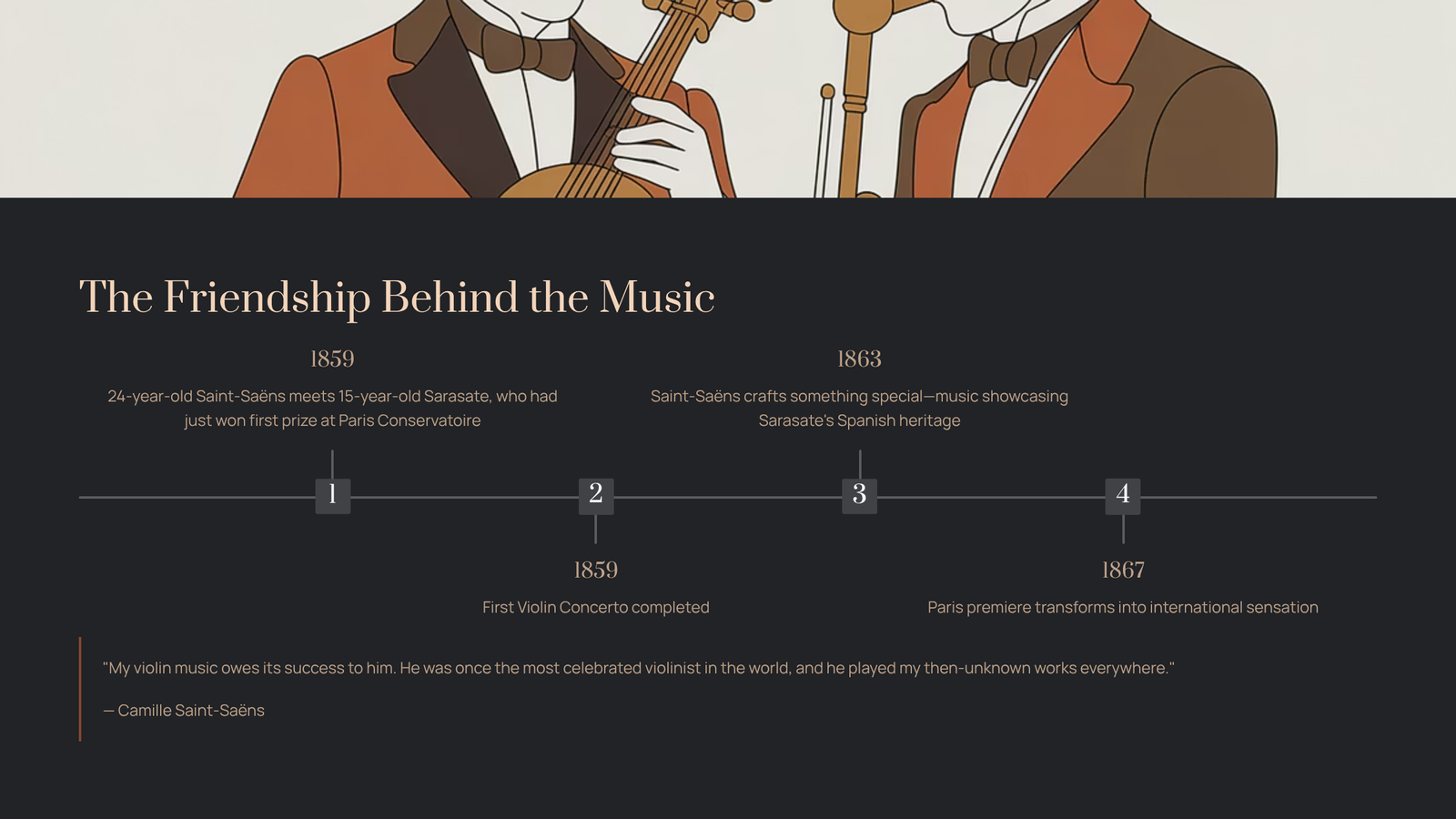

The story begins when a 24-year-old Saint-Saëns met a remarkably talented 15-year-old violinist from Pamplona, Spain. Pablo de Sarasate had just won first prize at the Paris Conservatoire, and he had a simple request: would Saint-Saëns write him a concerto?

Saint-Saëns agreed, and by 1859, his First Violin Concerto was complete. But the young composer wasn’t finished. Four years later, he crafted something special for Sarasate—a piece that would showcase not just technical brilliance, but the violinist’s Spanish heritage. The result was music that sounds like the soul of Spain filtered through French elegance.

Their partnership proved remarkably fruitful. As Saint-Saëns later wrote, “My violin music owes its success to him. He was once the most celebrated violinist in the world, and he played my then-unknown works everywhere.” Sarasate carried this piece across Europe and America, transforming it from a Parisian premiere into an international sensation.

From Sadness to Celebration

The genius of this work lies in its emotional architecture. Saint-Saëns creates a complete journey in just nine minutes, moving from introspective sorrow to unbridled joy.

The piece opens with “Andante malinconico”—a slow, melancholic passage where the solo violin sings a wistful melody over hushed orchestral chords. Picture autumn leaves falling, or a lone figure gazing at distant mountains. The melody rises and falls in sighing phrases, each one touched with a gentle sadness that never becomes heavy. This is French restraint at its finest: emotional, but never overwrought.

Then something shifts. The tempo quickens, the violin’s fingers begin to fly, and suddenly we’re somewhere else entirely. The Rondo bursts forth with a syncopated, dance-like theme that practically shouts “España!” The transformation is deliberate and dramatic—Saint-Saëns understood that contrast creates emotional power.

What Makes It Sound So Spanish?

Even listeners who know nothing about music theory can hear the Spanish flavor in this piece. But what creates that unmistakable character?

Saint-Saëns wove several elements into the Rondo that evoke Spanish folk music. The rhythm is heavily syncopated, with accents landing in unexpected places—a hallmark of flamenco and other Iberian dance forms. The melody contains chromatic inflections, those slightly unexpected notes that give Spanish music its distinctive color. And the overall energy suggests a festive dance, bodies in motion, castanets clicking.

There’s a clever technical trick at work as well. While the orchestra plays in 6/8 time (a lilting, waltz-like meter), the solo violin often plays in 2/4, creating a rhythmic tension that adds excitement without listeners consciously understanding why. It’s the musical equivalent of a dancer moving against the beat—controlled rebellion that heightens the drama.

How to Listen: A Section-by-Section Guide

For your first listen, don’t try to analyze. Just feel the journey from sadness to joy. But when you’re ready to go deeper, here’s what to notice:

The Introduction (first two minutes) establishes the melancholic mood. Listen for the violin’s falling phrases—notes that drop from high to low like sighs. Notice how the orchestra stays quietly supportive, never competing with the solo voice. Around the 1:20 mark, the tempo begins to accelerate, building anticipation for what’s coming.

When the Rondo arrives, you’ll know immediately. The mood transforms completely as that infectious Spanish theme enters. This theme will return multiple times throughout the piece, each time slightly different—sometimes quiet and intimate, sometimes thunderous with full orchestra.

Between statements of the main theme, listen for the contrasting lyrical passages marked “con morbidezza” (with tenderness). These gentle episodes provide breathing room before the next burst of virtuosity.

The Coda (final minute) is pure fireworks. The tempo increases to “Più allegro,” and the violinist unleashes every trick in the virtuoso playbook: rapid scales, double stops (playing two strings at once), flying arpeggios, and passages that climb to the violin’s highest register. It’s designed to leave audiences breathless—and it always does.

Recordings That Illuminate Different Facets

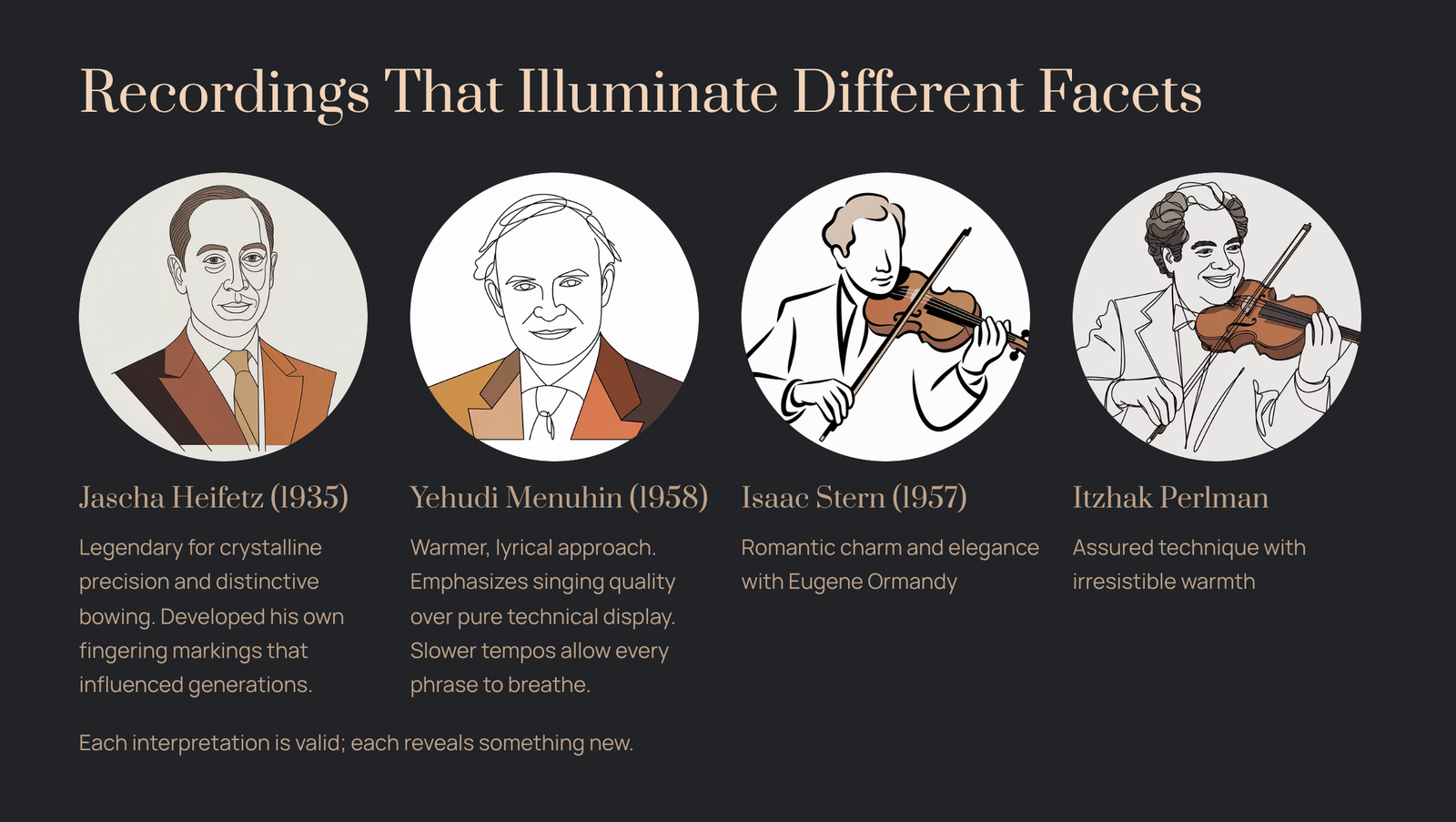

Different violinists reveal different dimensions of this music. Jascha Heifetz’s 1935 recording with the London Philharmonic remains legendary for its crystalline precision and distinctive bowing technique. Heifetz actually developed his own fingering and bowing markings for this piece, which influenced generations of violinists.

For a warmer, more lyrical approach, seek out Yehudi Menuhin’s 1958 recording with the Philharmonia Orchestra. Menuhin emphasizes the music’s singing quality over pure technical display, choosing slightly slower tempos that allow every phrase to breathe.

Isaac Stern’s 1957 recording with Eugene Ormandy brings romantic charm and elegance, while Itzhak Perlman’s various recordings showcase assured technique with irresistible warmth. Each interpretation is valid; each reveals something new.

The Quiet Revolutionary

Saint-Saëns occupies a fascinating position in music history. While contemporaries like Wagner and Berlioz pushed toward ever more radical experiments, Saint-Saëns maintained classical structure and clarity. Some dismissed him as conservative. But in pieces like this one, we hear something equally valuable: the ability to create immediate, visceral emotional impact within traditional forms.

The Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso doesn’t try to be revolutionary. It simply tries to be perfect at what it is: a showcase for violin virtuosity, a journey from melancholy to joy, a nine-minute drama that never wastes a moment. That Saint-Saëns achieved this at age 28 speaks to his remarkable gifts.

Why This Piece Still Matters

In an age of streaming and infinite musical choices, the Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso continues to fill concert halls and rack up millions of plays online. Its appeal is immediate and universal. You don’t need to understand music theory to feel the sadness of the opening or the exhilaration of the finale. You don’t need to know about Spanish folk music to sense the dance in your bones.

Perhaps that’s the ultimate lesson of this remarkable piece. Great music communicates directly, heart to heart, across centuries and cultures. Saint-Saëns and Sarasate, a French composer and a Spanish virtuoso, created something that speaks to everyone willing to listen.

Close your eyes, press play, and let the journey begin. In nine minutes, you’ll travel from autumn sadness to summer celebration—and understand why some finales simply refuse to stay hidden.