📑 Table of Contents

- Who Was Erik Satie? The Strangest Composer in Paris

- The Mysterious Title: What Does “Gymnopédie” Mean?

- Listening Guide: What to Notice in Gymnopédie No. 1

- Why This “Simple” Piece Is Actually Revolutionary

- Recommended Recordings: Three Different Journeys

- When to Listen: Creating Your Own Ritual

- The Legacy of Doing Less

In 1888, a peculiar 22-year-old Frenchman sat in a cramped Montmartre apartment and wrote something that confused everyone. The music had almost nothing in it. No virtuosic runs. No dramatic crescendos. Just a handful of notes floating in vast pools of silence.

Critics dismissed it. Audiences ignored it. But that strange young man—Erik Satie—had accidentally invented the future of music.

Today, Gymnopédie No. 1 has been streamed billions of times. It appears in films, commercials, and meditation apps worldwide. You’ve almost certainly heard it, even if you didn’t know its name.

So what makes a piece with barely any notes one of the most beloved piano works ever written?

Who Was Erik Satie? The Strangest Composer in Paris

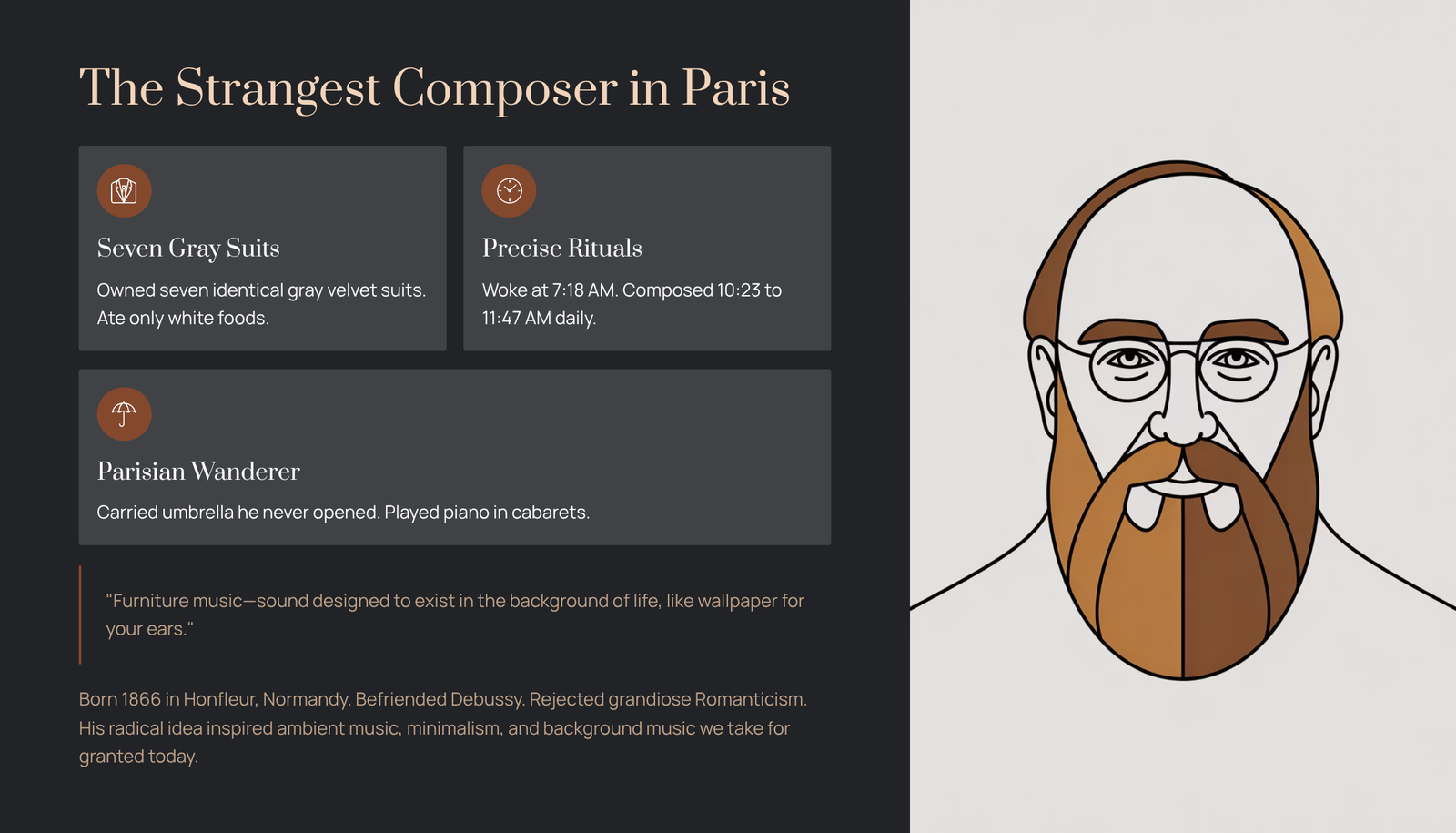

Erik Satie was not your typical classical composer. He owned seven identical gray velvet suits and ate only white foods—rice, eggs, coconut, and fish bones cooked in cotton water. He claimed to wake at 7:18 AM precisely and compose from 10:23 to 11:47 AM. Whether these eccentricities were genuine or elaborate performance art, no one ever knew for certain.

Born in Honfleur, Normandy, in 1866, Satie moved to Paris and quickly became a fixture in the city’s artistic underground. He played piano in cabarets, befriended Claude Debussy, and spent his days wandering the city with an umbrella he never opened.

Satie rejected the grandiose Romanticism that dominated his era. While other composers were building symphonic cathedrals, he was whittling music down to its bones. He called his approach “furniture music”—sound designed to exist in the background of life, like wallpaper for your ears.

This radical idea, dismissed as a joke in his lifetime, would eventually inspire ambient music, minimalism, and the entire concept of background music we take for granted today.

The Mysterious Title: What Does “Gymnopédie” Mean?

The word “Gymnopédie” puzzled listeners from the start. Satie borrowed it from ancient Greece, where the gymnopaedia was a festival in Sparta featuring naked young men dancing to honor Apollo.

But don’t expect athletic energy here. Satie transformed this reference into something entirely different—slow, contemplative, almost ritualistic in its calm. Perhaps he saw poetry in the contrast: the disciplined bodies of ancient dancers frozen into pure, unhurried sound.

The title itself became part of Satie’s mystique. He loved naming pieces with obscure, sometimes invented words. Later works would carry names like “Genuine Flabby Preludes (for a Dog)” and “Dried Up Embryos.” For Satie, music should spark curiosity before a single note was played.

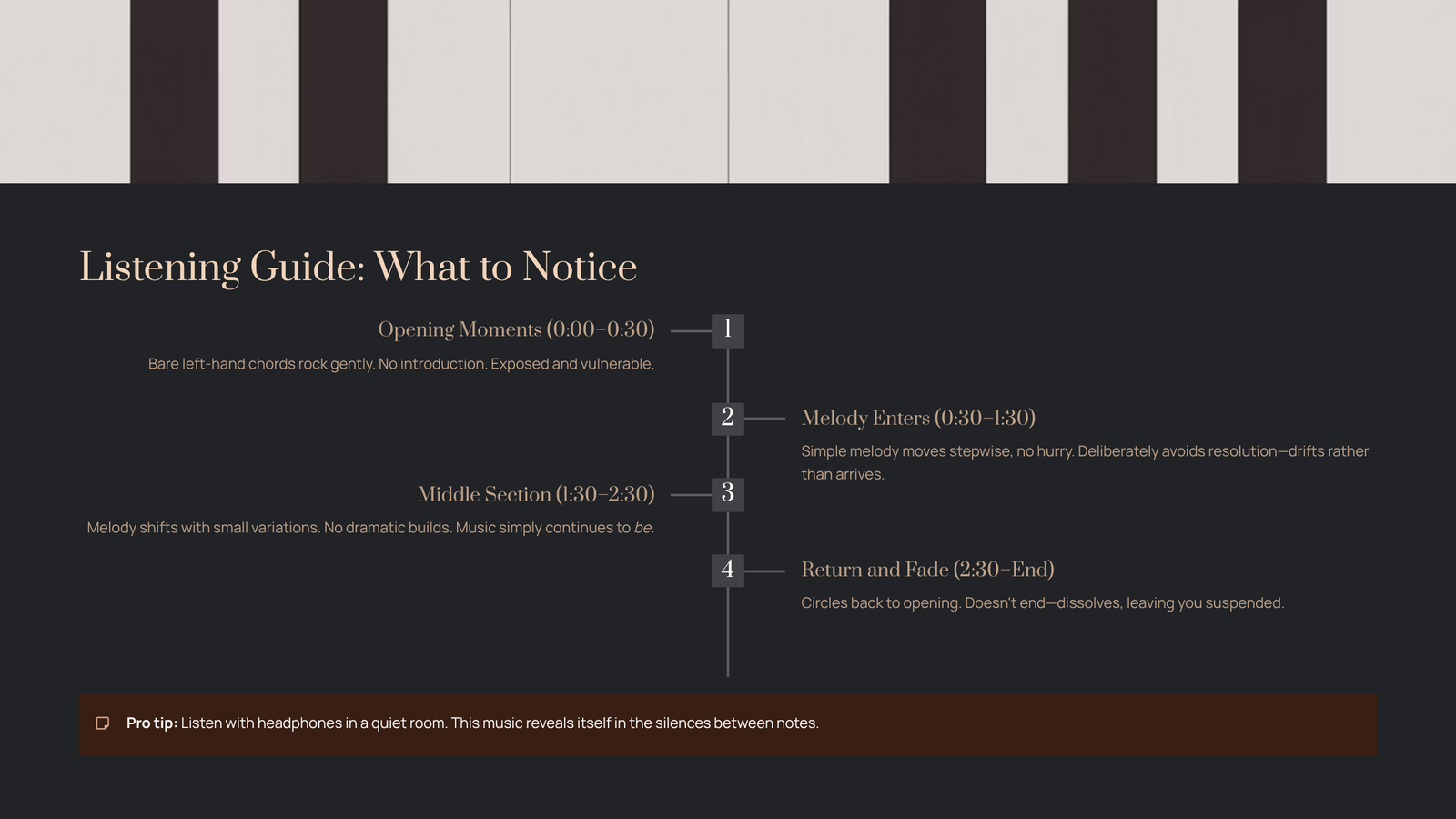

Listening Guide: What to Notice in Gymnopédie No. 1

If you’re new to this piece, here’s how to let it work its magic:

The Opening Moments (0:00–0:30)

The piece begins with bare left-hand chords—just two alternating harmonies that rock gently back and forth. There’s no introduction, no preparation. You’re simply dropped into this peaceful world. Notice how exposed and vulnerable these opening chords feel. Nothing is hidden.

The Melody Enters (0:30–1:30)

A simple melody appears in the right hand, moving stepwise with no hurry. Satie deliberately avoids resolution—the tune drifts rather than arrives. This creates that hypnotic, floating quality. Try not to anticipate where it’s going. Just follow.

The Middle Section (1:30–2:30)

The melody shifts slightly, introducing small variations. But Satie resists any temptation to develop his material in the traditional sense. There are no dramatic builds. The music simply continues to be, like watching clouds pass.

The Return and Fade (2:30–End)

We circle back to the opening material. The piece doesn’t really end—it dissolves, leaving you suspended in that strange, quiet space it created.

Pro tip: Listen with headphones in a quiet room. This music reveals itself in the silences between notes as much as in the notes themselves.

Why This “Simple” Piece Is Actually Revolutionary

Musicians often describe Gymnopédie No. 1 as “easy to play, impossible to play well.” The notes are accessible to intermediate pianists, but capturing the spirit? That takes something else entirely.

Satie strips away everything classical music traditionally relies on—virtuosity, complexity, narrative arc. What remains is pure atmosphere. Each note must breathe. Each silence must speak.

This was radical in 1888. Romantic composers were still piling on more instruments, more dynamics, more everything. Satie looked at this arms race and simply walked away. He proved that restraint could be more powerful than excess.

His influence echoes everywhere today: in Brian Eno’s ambient experiments, in the meditative works of Max Richter, in every lo-fi study playlist that understands the power of less.

Recommended Recordings: Three Different Journeys

For First-Time Listeners: Reinbert de Leeuw

De Leeuw’s recording takes the tempo extremely slow—almost dangerously so. But this radical interpretation reveals hidden depths in every chord. It demands patience and rewards it.

For the Classic Interpretation: Pascal Rogé

Rogé’s Decca recording is warm, balanced, and accessible. This is the version you’ve probably heard in movies and coffee shops. A perfect entry point.

For a Modern Touch: Alexandre Tharaud

Tharaud brings subtle rubato and a contemporary sensibility. His interpretation feels conversational, like Satie speaking directly to our stressed, overstimulated era.

YouTube Recommendation: Search for Reinbert de Leeuw’s complete Satie recordings. His approach transforms these short pieces into profound meditative experiences.

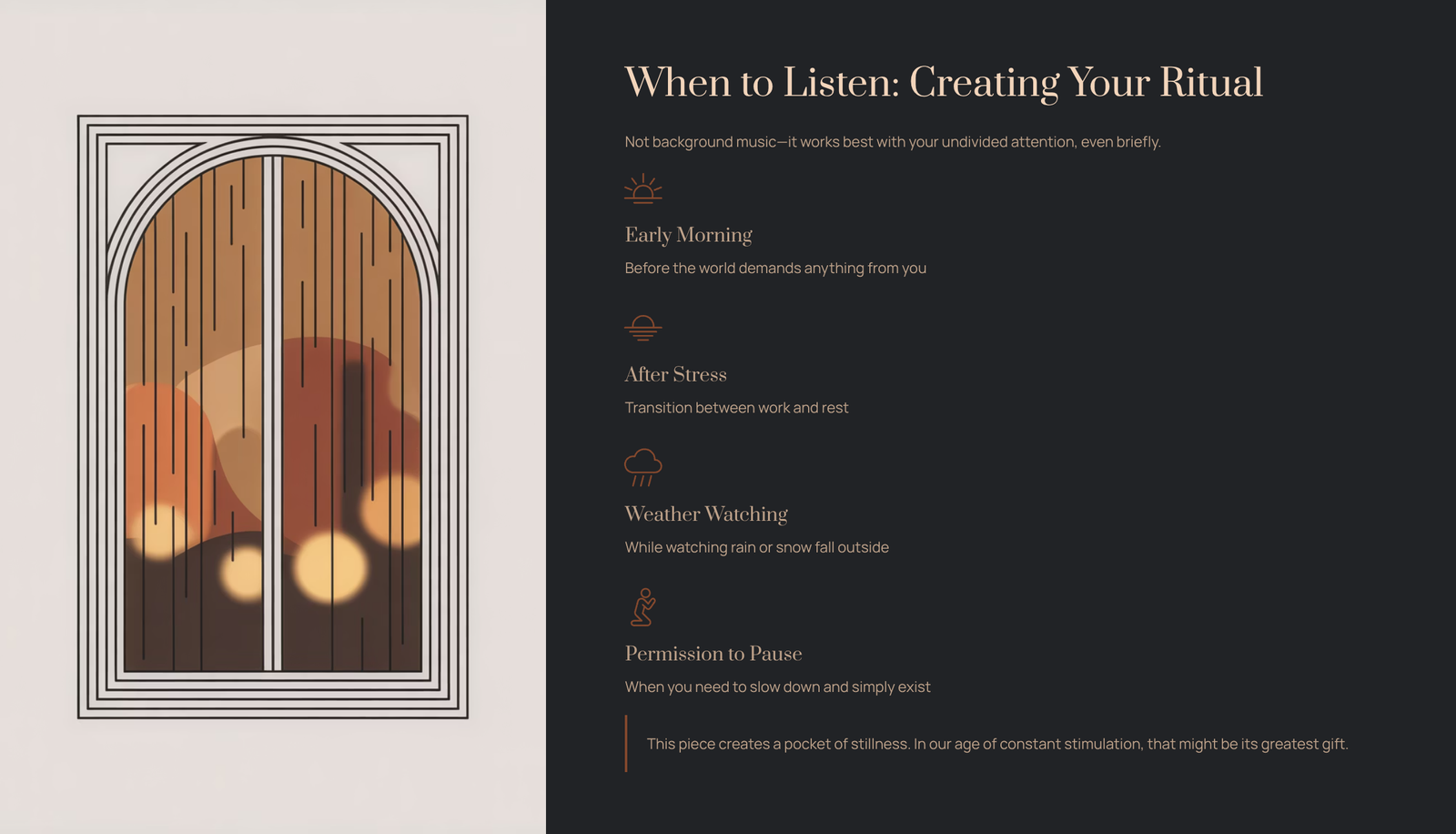

When to Listen: Creating Your Own Ritual

Gymnopédie No. 1 isn’t background music—despite Satie’s “furniture music” philosophy. It works best when you give it your undivided attention, even briefly.

Try it during these moments:

– Early morning, before the world demands anything from you

– After a stressful day, as a transition between work and rest

– While watching rain or snow fall outside your window

– When you need permission to slow down and simply exist

This piece doesn’t solve problems or energize you for tasks. It creates a pocket of stillness. In our age of constant stimulation, that might be its greatest gift.

The Legacy of Doing Less

Erik Satie died in 1925, poor and largely forgotten. When friends entered his cluttered apartment afterward, they found hundreds of unpublished compositions, letters he’d never sent, and those seven identical gray suits.

It took decades for the world to understand what he’d created. Now, Gymnopédie No. 1 accompanies countless moments of human life—births, deaths, quiet dinners, sleepless nights.

Satie proved that music doesn’t need to impress. Sometimes it just needs to be there, holding space for whatever you’re feeling.

In three minutes of gentle piano, an eccentric Frenchman from 1888 still offers us exactly what we need: permission to slow down, breathe, and simply exist.