Table of Contents

Whispers from the Darkness

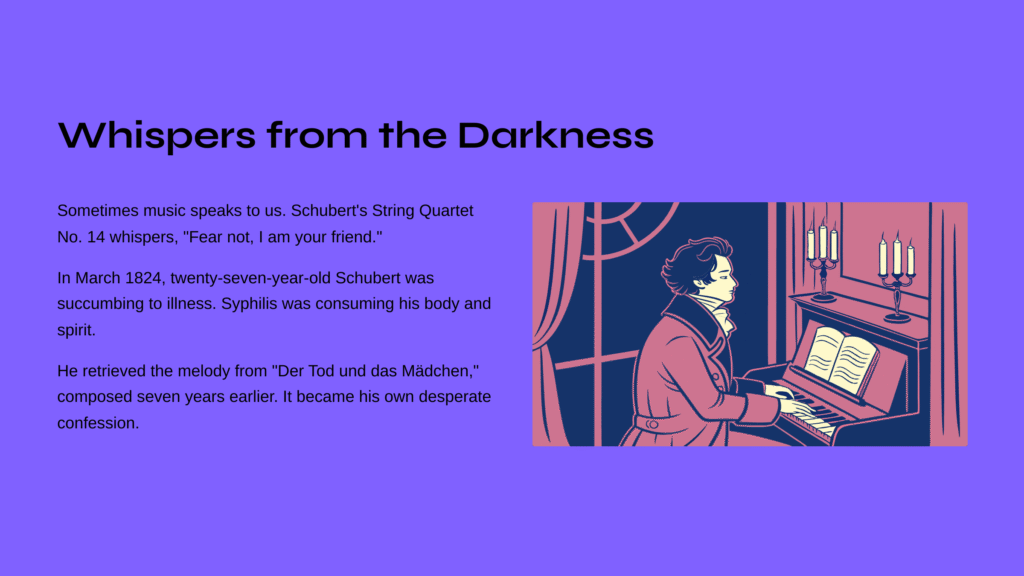

Sometimes music speaks to us. When listening to the second movement of Schubert’s String Quartet No. 14 “Death and the Maiden,” it feels as if someone places a hand on my shoulder and whispers quietly, “Fear not, I am your friend.” These words are both Death’s comfort to the Maiden and Schubert’s final greeting to himself—and to us.

In March 1824, twenty-seven-year-old Schubert knew his body was succumbing to illness. Syphilis, a fatal disease for his time, was gradually consuming his body and spirit. It was no coincidence that he retrieved the melody from his song “Der Tod und das Mädchen,” composed seven years earlier. Now, that song had transcended mere poetic interpretation to become the composer’s own desperate confession.

Birth of a Work That Harbors Time

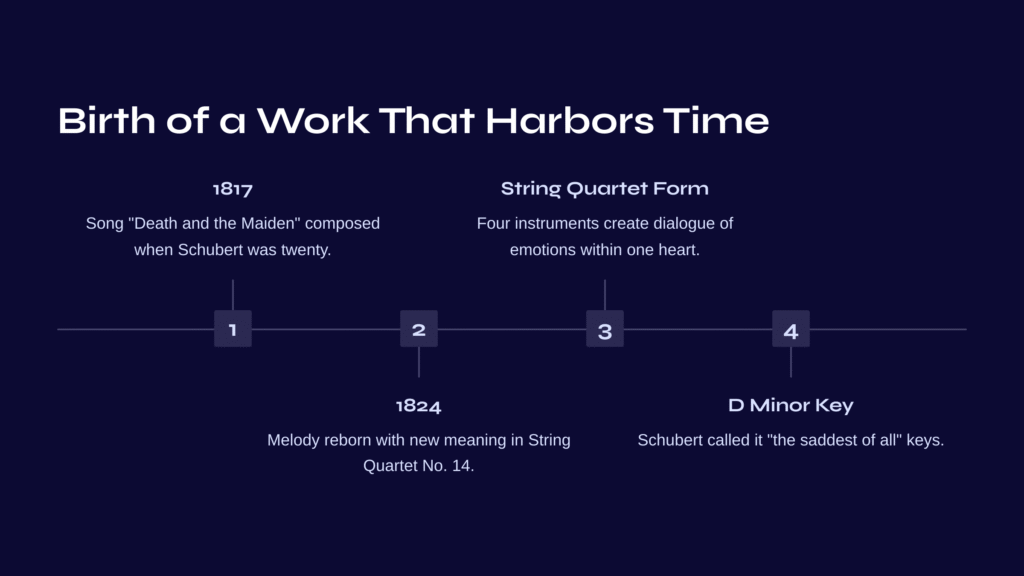

The song “Death and the Maiden,” inspired by Matthias Claudius’s poem, was born in 1817 when Schubert was twenty. At that time, death might have been merely an abstract concept for him. But seven years later, that melody was reborn with entirely different meaning.

The choice of string quartet form is itself significant. The intimate yet complex resonance created by four string instruments resembles a dialogue of various emotions occurring within one person’s heart. Schubert set this entire quartet in D minor, a key he called “the saddest of all.”

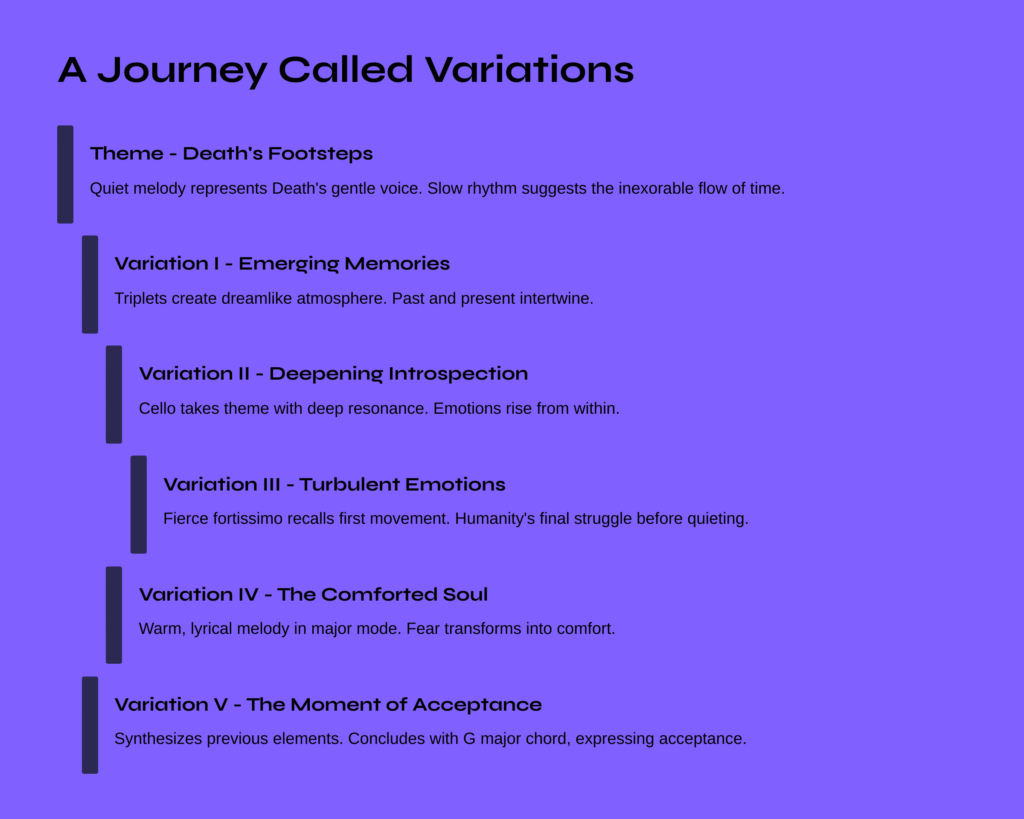

A Journey Called Variations

The second movement “Andante con moto” consists of a theme and five variations. Beginning in G minor, this movement unfolds slowly and solemnly like a funeral march. Yet this is not simply an expression of sorrow. Through each variation, Schubert presents different perspectives on death.

Theme – Death’s Footsteps The theme quietly presented by the first violin directly incorporates the piano part from the original song. The slow but steady rhythm suggests something as inexorable as the flow of time itself. What’s crucial here is that this melody represents Death’s voice—not threatening, but rather gentle.

Variation I – Emerging Memories While the first violin plays a melody decorated with triplets, the other instruments maintain a pulse-like regular rhythm. A dreamlike atmosphere is created, as if floating through memories. It’s a moment where past and present intertwine.

Variation II – Deepening Introspection Now the cello takes the theme. As the theme unfolds in low, deep resonance, the first violin adds decoration with rapid sixteenth notes. It’s as if emotions rising from deep within the heart are surfacing.

Variation III – Turbulent Emotions Suddenly the atmosphere changes. The fierce melody played fortissimo recalls the “Sturm und Drang” spirit of the first movement. Is this humanity’s final struggle before death? But soon it quiets again. Even anger is ultimately just a passing emotion.

Variation IV – The Comforted Soul Like the major-mode section in the original song, this variation is warm and lyrical. A gentle melody flows as if someone is tenderly patting one’s back. It’s the moment when fear transforms into comfort.

Variation V – The Moment of Acceptance The final variation synthesizes all the elements that have appeared before. And finally, it concludes with a G major chord. The shift from minor to major is not merely a compositional technique. This is the musical expression of acceptance. The moment when the Maiden, and Schubert, finally reconcile with Death.

My Own Listening, My Own Feeling

Listening to this music, I often wonder: Did Schubert truly accept death? Or did he want to accept it? What I feel in the music is not complete peace, but rather a yearning for peace.

Especially when hearing that final G major chord, a sense of relief washes over me like a long sigh. Yet behind that relief, there’s still a mixture of regret and reluctance to let go. Isn’t this the essence of Schubert’s musical genius? Showing human complexity rather than complete resolution.

Sometimes while listening to this piece, I reflect on my own fears. Even without the grand theme of death, we face countless “endings” in life. The end of relationships, the end of dreams, the end of certain eras. In such moments, Schubert’s music whispers to me: “Fear not, every ending is another beginning.”

Suggestions for Deeper Listening

If you’re hearing this piece for the first time, I recommend starting with the original song “Der Tod und das Mädchen.” Begin with recordings by great singers like Fischer-Dieskau or Schwarzkopf. Simply feeling the difference between the song’s simple structure and the quartet’s complex variations can be deeply moving.

Next, pay attention to the characteristics of each variation. Focus especially on the dramatic change from the third to fourth variation, and the shift from minor to major at the end. In these moments, you can feel Schubert’s true message.

For recordings, I recommend the Alban Berg Quartet or the Tetzlaff Quartet. Each offers different interpretations, making it enjoyable to compare multiple versions.

A Dialogue Across Time

Schubert died in 1828, four years after completing this quartet, at the young age of thirty-one. The death he feared ultimately found him. But his music lives on. More precisely, it continues to be reborn.

Every time someone performs this piece, every time someone listens, Schubert’s confession is born anew. His fear of death and his acceptance, those complex emotions resonate within us once again. Isn’t this true immortality?

Few works demonstrate the meaning of music transcending time as well as this one. Schubert of 1824 and we of 2025 dialogue through the same melody. Through the theme of death, through emotions of fear and comfort. And this dialogue will continue. As long as someone needs this music, Schubert’s whispers will resonate eternally.

The Next Journey: Beethoven’s Gentle Whisper

After Schubert’s profound introspection, it’s refreshing to encounter music of a different sensibility. Beethoven’s “Romance for Violin and Orchestra No. 2 in F Major, Op. 50” reveals a side quite different from the passionate Beethoven we know. Composed in 1798, when the twenty-eight-year-old Beethoven faced the terror of hearing loss, this piece holds a tranquility like the calm before a storm.

The pastoral atmosphere of F major provides a peaceful, bright feeling, filled with lyrical and beautiful melodies that seem to deny Beethoven’s own reality. As the tempo marking “Adagio cantabile” suggests, this piece should be played “in a singing manner.”

Structured in rondo form, this work returns with new clothing each time the theme repeats. The charming melody immediately begun by the violin is soon taken up by the orchestra, with strong dotted rhythms in the accompaniment marking the end of the first section. After a more active contrasting section with hints of minor mode, the familiar theme returns again.

What’s most striking about this romance is Beethoven’s gentle side. While truly making the violin sing, the orchestral accompaniment remains very much in the background while providing the lovely “Viennese” sound of a small orchestra. If Schubert’s variations dealt with the weighty theme of death, Beethoven’s romance pursues pure beauty itself.

Both works demonstrate the comfort music can provide in the face of human fragility. Schubert through deep introspection, Beethoven through pure beauty. Perhaps this is the greatest gift classical music gives us—the power of music to console our hearts in any situation.