Table of Contents

The Paradox I Couldn’t Ignore

How do you write music about silence?

This question stopped me mid-breath the first time I encountered Federico Mompou’s Música Callada—literally translated as “Silent Music.” It felt like a koan, one of those impossible riddles that Zen masters pose to shatter ordinary thinking. Music is sound. Silence is its absence. How could they possibly coexist?

And yet, in the opening bars of “Angelico,” the first piece from Book I, I heard it: the sound between sounds. The resonance that lives in the space after a bell stops ringing. The prayer that happens not in the words, but in the breath between them.

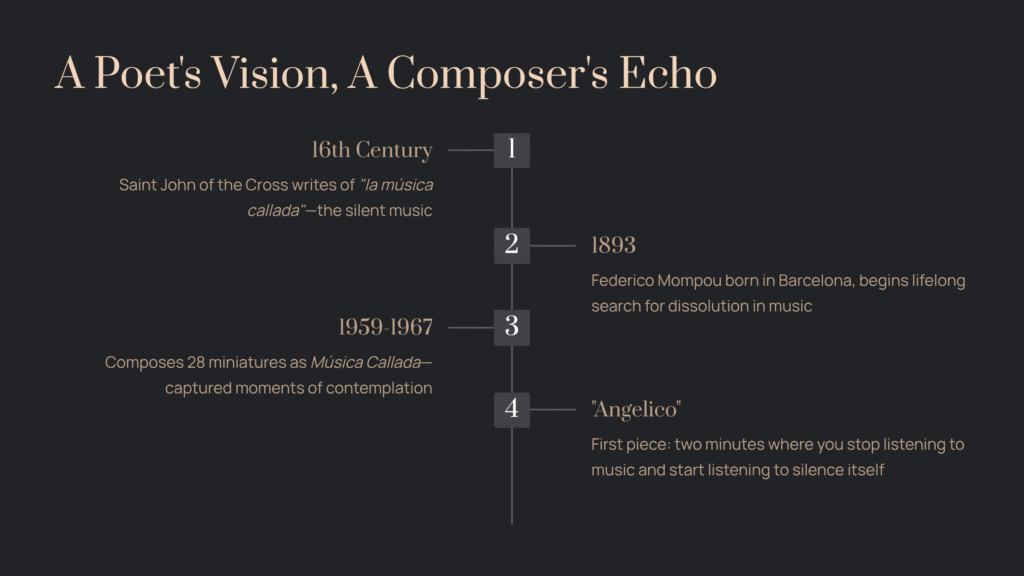

A Poet’s Vision, A Composer’s Echo

Mompou didn’t invent this paradox—he borrowed it from a 16th-century Spanish mystic named Saint John of the Cross. In his poem Spiritual Canticle, the saint wrote of “la música callada”—the silent music—and “la soledad sonora”—the sounding solitude. These weren’t metaphors for him. They were descriptions of what happens when you pray so deeply that words dissolve into pure presence.

Born in Barcelona in 1893, Mompou spent his life searching for this same dissolution in music. He wasn’t interested in grand symphonies or virtuosic displays. Instead, he turned inward, creating what he called “miniatures”—small, intimate piano pieces that felt less like compositions and more like captured moments of contemplation.

Between 1959 and 1967, he wrote twenty-eight of these miniatures, collected as Música Callada. “Angelico,” the first, lasts barely two minutes. But in that brief span, something extraordinary happens: you stop listening to music and start listening to silence itself.

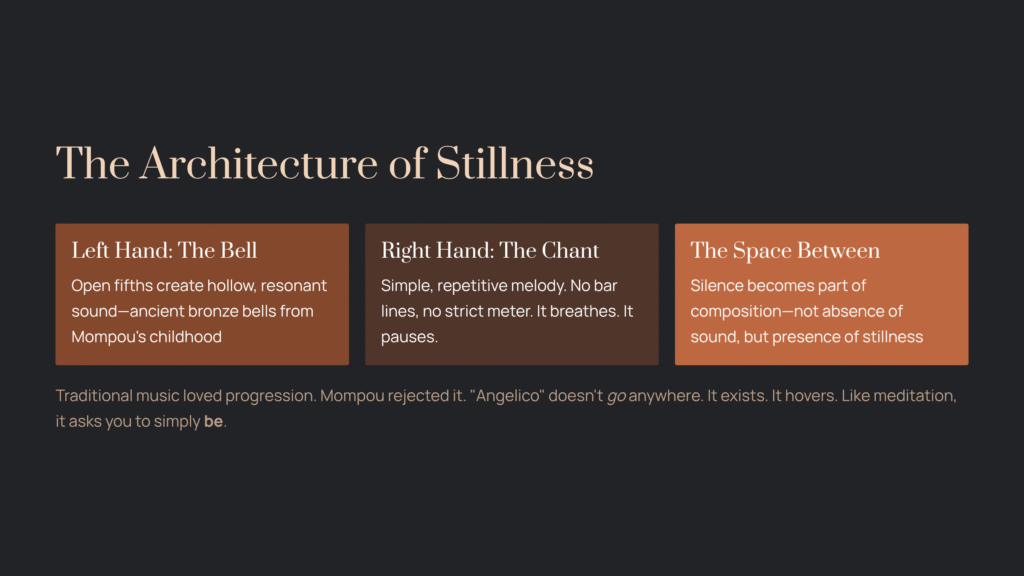

The Architecture of Stillness

Let me tell you what makes this piece so unusual—not in technical terms, but in the way it feels.

When pianists play “Angelico,” their left hand creates what musicians call “open fifths”—two notes separated by a specific interval that creates a hollow, resonant sound. But forget the theory for a moment. Close your eyes and listen. What you’ll hear is the sound of an ancient bell, cast in bronze, hanging in a stone tower somewhere in medieval Spain.

This bell-sound wasn’t accidental. Mompou’s mother came from the Dencausse family, legendary bell-makers in Catalonia. He grew up surrounded by bells—their shimmer, their decay, the way their vibrations seemed to continue even after the sound had technically stopped. That lingering resonance, that almost-silence, became the foundation of his musical language.

The right hand, meanwhile, plays something that barely qualifies as a melody. It’s more like a chant—simple, repetitive, unadorned. There are no bar lines here, no strict meter forcing the music forward. Instead, it breathes. It pauses. It allows silence to be part of the composition, not just the absence of sound.

Traditional Western music from the 18th and 19th centuries loved progression—tension and release, question and answer, movement toward resolution. Mompou rejected all of that. “Angelico” doesn’t go anywhere. It exists. It hovers. Like meditation itself, it asks you to let go of the need for arrival and simply be with the present moment.

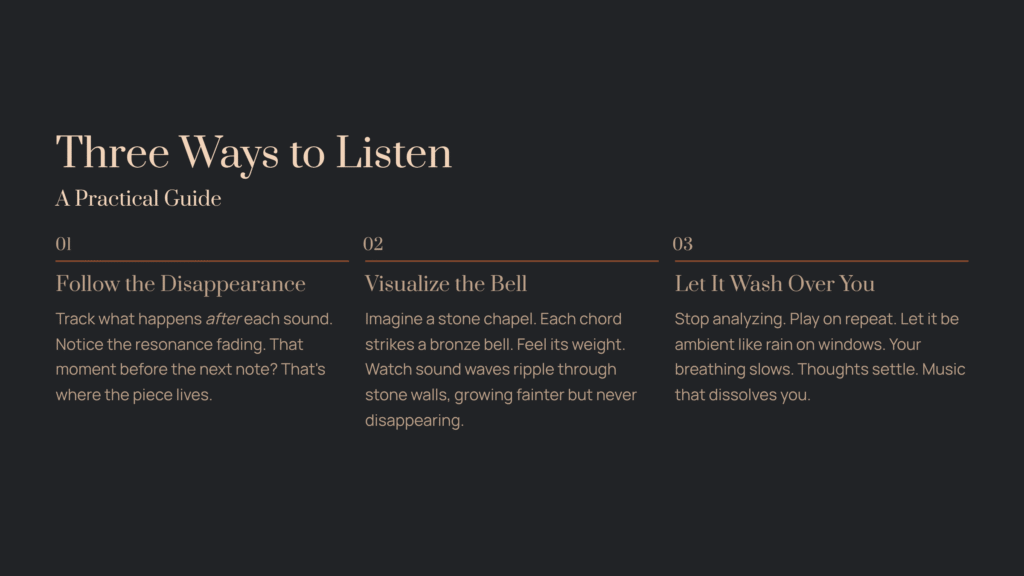

Three Ways to Listen: A Practical Guide

I’ve learned that this piece reveals itself differently depending on how you approach it. Here are three listening modes I return to:

First Listening: Follow the Disappearance

Play “Angelico” through headphones in a quiet room. But don’t just listen to the notes—track what happens after each sound. Notice how the piano’s resonance fades. There’s a moment, right before the next note arrives, where you’re suspended in an almost-silence. That’s where the piece actually lives. Mompou once said he wanted to capture “the space around the sound.” This is what he meant.

Second Listening: Visualize the Bell

This time, imagine you’re standing in a small stone chapel. Above you hangs a single bronze bell. Each chord in the left hand is that bell being struck. Feel its weight. See the metal shiver. Watch the sound waves ripple outward through the stone walls, growing fainter but never quite disappearing. The melody in the right hand? That’s your own breath, your own prayer, offered into the reverberating space.

Third Listening: Let It Wash Over You

Here’s where you stop analyzing altogether. Lie down. Let the piece play on repeat—three, four, five times in succession. Don’t try to follow the structure or identify the harmonies. Just let it be ambient, like rain on a window or waves on a shore. You might find your breathing slows. Your thoughts settle. This is the meditative power Mompou was reaching for: music that doesn’t entertain you but dissolves you.

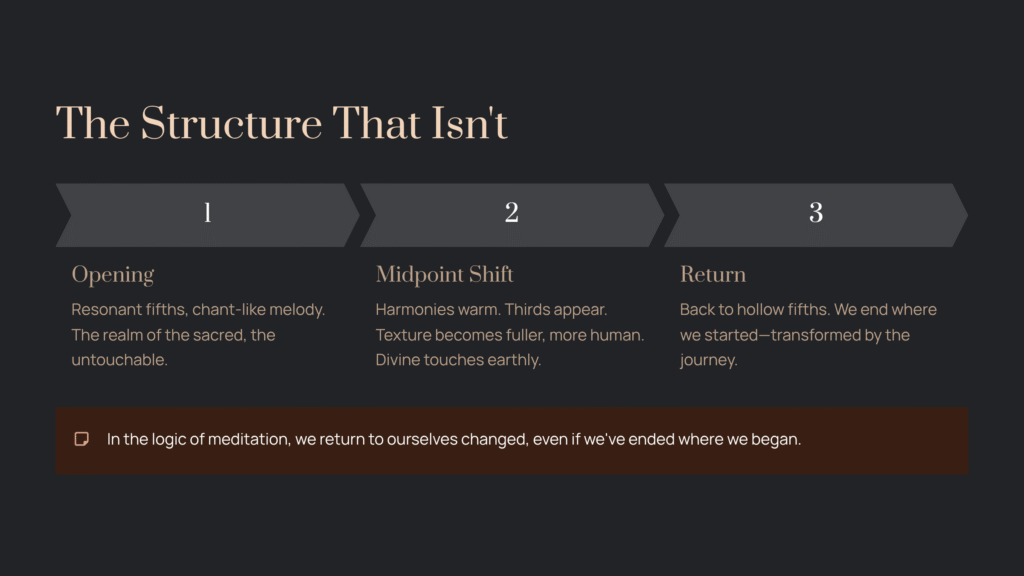

The Structure That Isn’t

I should mention that “Angelico” does have a form, though calling it “structure” feels too rigid. Think of it more as a gentle wave:

The piece opens with those resonant fifths—the bell-sound—and the chant-like melody floating above. This is the realm of the sacred, the untouchable. Then, about halfway through, something shifts. The harmonies warm. Thirds appear (the intervals that sound “major” or “minor” to Western ears). The texture becomes slightly fuller, more human. It’s as if the divine has bent down to touch the earthly.

But this warmth doesn’t last. By the end, we return to those open, hollow fifths. The piece concludes exactly as it began—not because nothing has changed, but because, in the logic of meditation, we return to ourselves transformed by the journey, even if we’ve ended where we started.

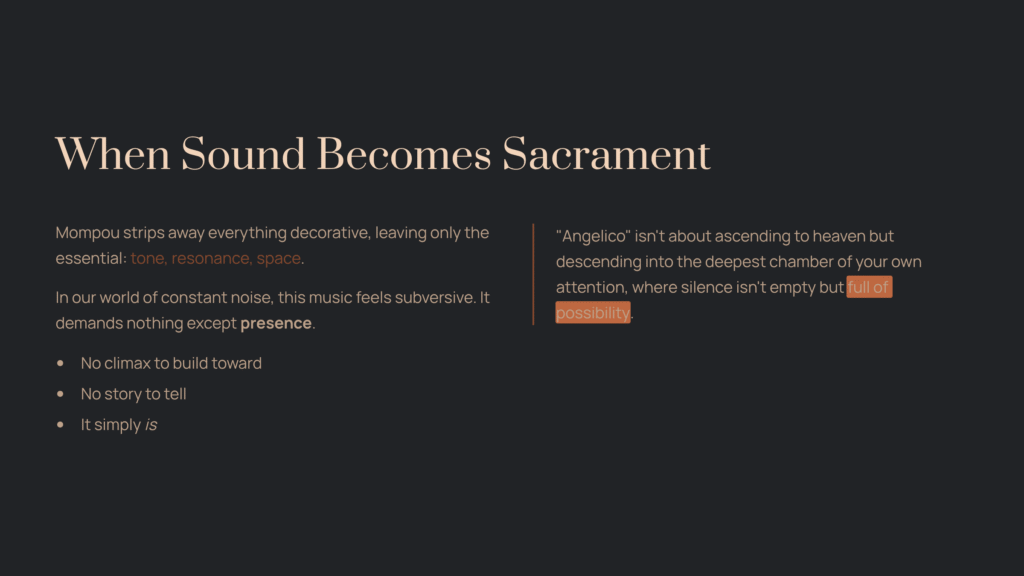

When Sound Becomes Sacrament

I’m not a religious person, but I understand why “Angelico” moves me the way it does. There’s something in its radical simplicity—its refusal to entertain, to seduce, to perform—that feels like an offering. Mompou strips away everything decorative and leaves only the essential: tone, resonance, space.

In our world of constant noise and stimulation, this kind of music feels almost subversive. It demands nothing from you except presence. It doesn’t build to a climax. It doesn’t tell a story. It simply is, the way a candle flame is, or a breath, or the gap between thoughts.

The title “Angelico” (meaning “angelic”) suggests something celestial, but I think the piece is more intimate than that. It’s not about ascending to heaven but descending into the deepest chamber of your own attention, where silence isn’t empty but full—full of possibility, full of presence, full of that mysterious “music” that exists beyond sound.

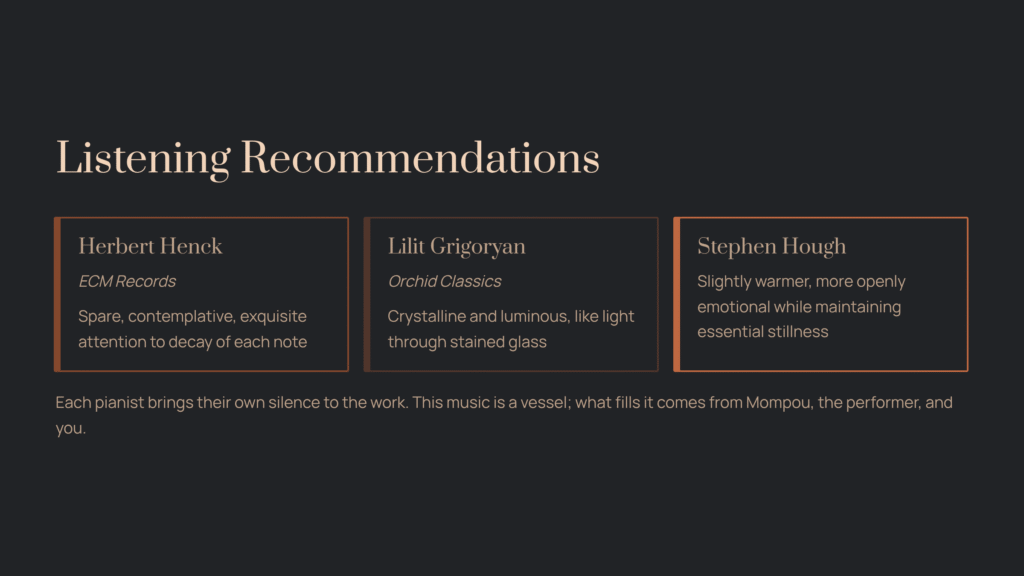

Listening Recommendations

If you want to experience “Angelico” in its full glory, I recommend:

- Herbert Henck’s recording on ECM Records—spare, contemplative, with exquisite attention to the decay of each note

- Lilit Grigoryan’s version on Orchid Classics—crystalline and luminous, like light through stained glass

- Stephen Hough’s interpretation—slightly warmer, more openly emotional while maintaining the piece’s essential stillness

Each pianist brings their own silence to the work, which is as it should be. This music is a vessel; what fills it comes partly from Mompou, partly from the performer, and partly from you.

A Final Thought

The first time I heard “Angelico,” I thought it was too simple, too slow, not enough. I wanted more melody, more drama, more something. But I kept returning to it, the way you might return to a favorite prayer or a particular view from a hilltop. And slowly—so slowly I didn’t notice it happening—the piece opened.

Not because it changed, but because I did. I learned to hear the silence. I learned to value the space. I learned that sometimes the most profound music is the music that knows when to stop talking and simply listen.

Mompou’s “Silent Music” doesn’t give answers. It gives you a space in which to hear your own questions more clearly. In a world that never stops shouting, that might be the most radical gift music can offer.

Let the bell ring. Let it fade. And in that fading, find yourself.