Table of Contents

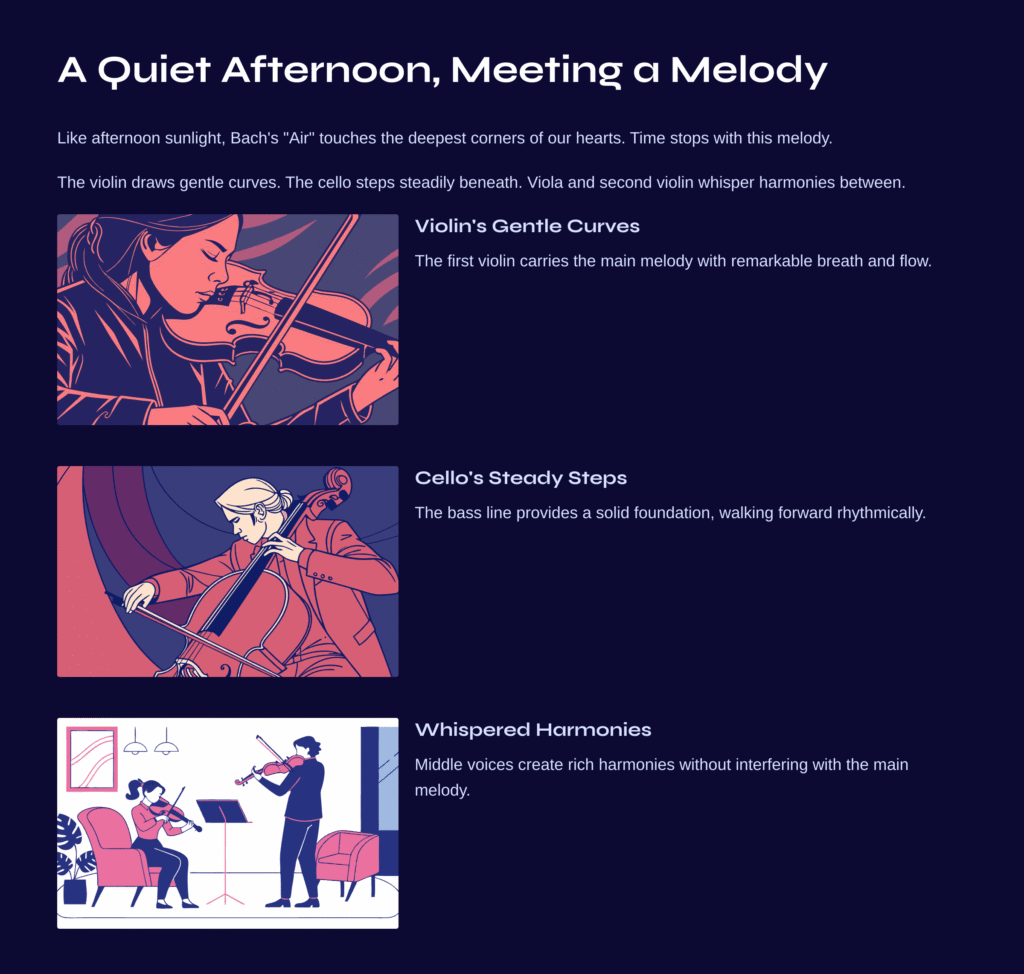

A Quiet Afternoon, Meeting a Melody

Like afternoon sunlight suddenly streaming through a window, certain music touches the deepest corners of our hearts without warning. The second movement “Air” from Bach’s Orchestral Suite No. 3 is exactly that kind of music. The first time I heard this melody, I felt as if time had stopped. Over the gentle curves drawn by the violin, the cello’s steady steps layer in, while the viola and second violin whisper harmonies into the spaces between.

This is not merely a dance piece. It’s a musical miracle, born in a Leipzig concert hall 300 years ago, that continues to comfort countless souls to this day. Why does this few-minute melody continue to be beloved across centuries? Let’s enter Bach’s musical world to find that answer.

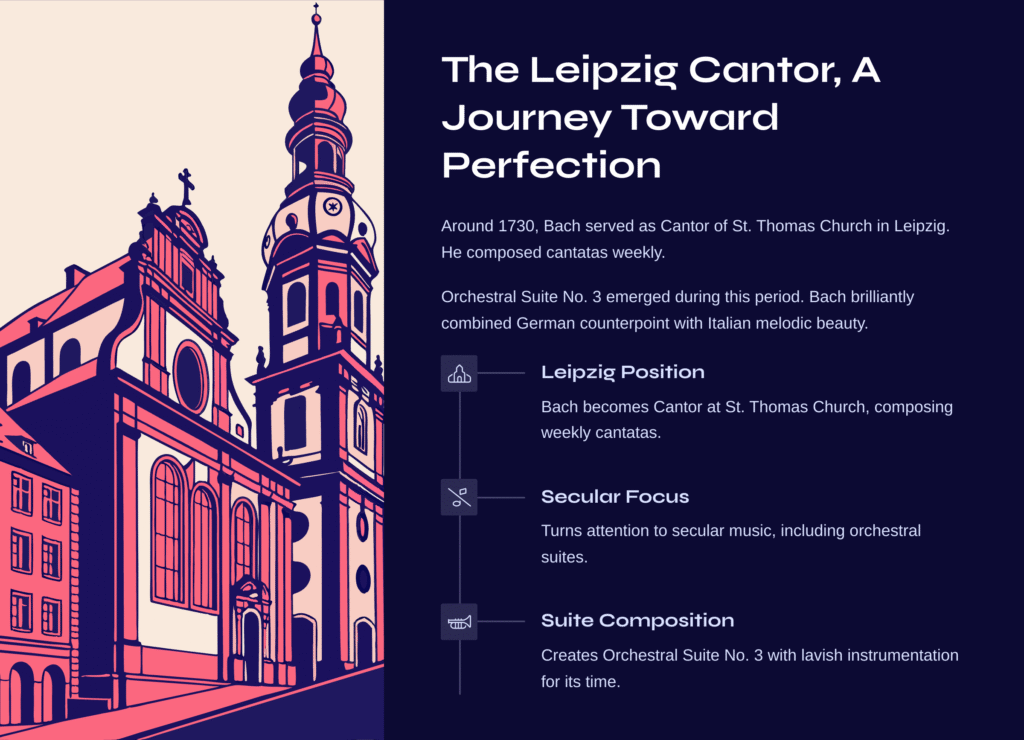

The Leipzig Cantor, A Journey Toward Perfection

Around 1730, Johann Sebastian Bach was living busy days as Cantor of St. Thomas Church in Leipzig. Along with his weekly obligation to compose cantatas, he was also turning his attention to secular music. Orchestral Suite No. 3, BWV 1068, is a product of precisely this period.

Baroque orchestral suites follow the tradition of French court dance music. Typically beginning with an overture and followed by various dance movements, Bach brilliantly combined German counterpoint with Italian melodic beauty within this framework. Composed for three trumpets, timpani, two oboes, strings, and basso continuo, this work featured quite a lavish instrumentation for its time.

But the second movement, “Air,” is an exception. Excluding all winds and brass, it’s performed by strings alone. Like a quiet moment of meditation arriving in the midst of a splendid feast.

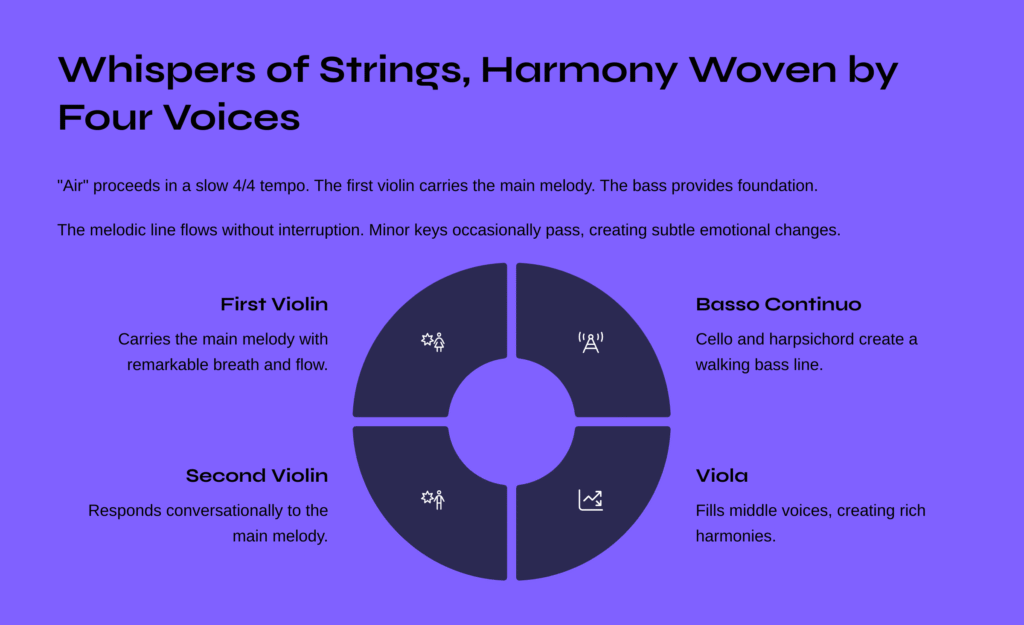

Whispers of Strings, Harmony Woven by Four Voices

“Air” proceeds in a slow 4/4 tempo. The first violin carries the main melody, the basso continuo (cello and harpsichord) walks through calm bass lines, while the second violin and viola fill in the middle voices.

The first violin’s melody has remarkable breath. Like reading a long sentence in one deep inhalation, the melodic line flows without interruption. Above the bright colors of D major, shadows of minor keys occasionally pass, creating subtle emotional changes. Following this melody, one realizes how meticulously Bach placed each note.

The bass line offers another charm entirely. It demonstrates the archetype of a “walking bass,” stepping forward regularly and rhythmically. Yet it’s not mere repetition—it changes sensitively according to harmonic progressions, providing solid foundation for the melody. Like the reliable shoulder of a trusted friend.

The second violin and viola create rich harmonies without interfering with the main melody. Sometimes responding conversationally to the main melody, sometimes quietly supporting it, the four voices achieve perfect balance.

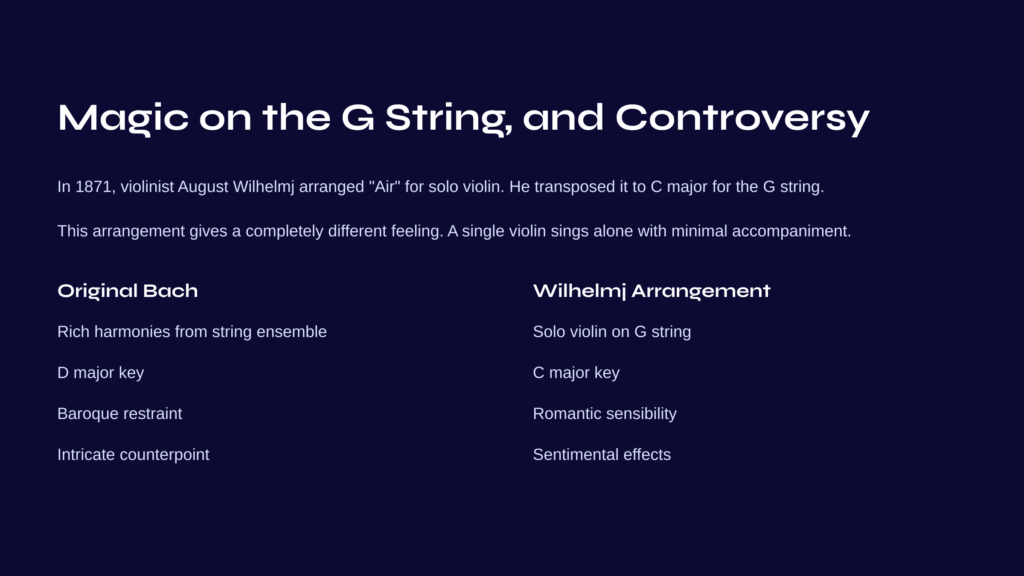

Magic on the G String, and Controversy

In 1871, German violinist August Wilhelmj arranged this “Air” for solo violin. He transposed the originally D major piece to C major, making it playable entirely on the violin’s lowest string—the G string. This became the famous “Air on the G String.”

Wilhelmj’s arrangement gives a completely different feeling from Bach’s original. Instead of the rich harmonies created by the string ensemble, a single violin sings alone. The accompaniment is reduced to a minimum, using pianissimo and mutes to emphasize a romantic atmosphere. The restrained beauty of the Baroque was reborn with 19th-century Romantic sensibility.

Violinist Joseph Joachim of the time harshly criticized this arrangement as a “shameless falsification.” He argued that it damaged Bach’s intricate contrapuntal structure while pursuing only sentimental effects. Ironically, however, Wilhelmj’s arrangement became more widely known than Bach’s original.

Resonance in My Heart, Comfort Across Time

Listening to this music, I often wonder: What did Bach feel while writing this melody? Why do we, living in a completely different era 300 years later, still find our hearts captivated by this music?

Perhaps the answer lies in the “balance” this music contains. Not joy, not sorrow, but somewhere in between—a quiet point. Not resignation, not hope, but the tranquility of accepting the present as it is. Listening to “Air,” I feel as if I’m floating on a deep lake. There are waves, but they’re gentle; there’s depth, but it’s not heavy.

Especially for modern people exhausted by stress, this music holds special meaning. Beauty that exists without conditions. A melody that needs no proof or display, sufficient in itself. Isn’t this true comfort?

Three Points for Deeper Listening

First, pay attention to the bass line. While it’s easy to focus only on the main melody, following the movement of the cello’s bass part allows you to better feel the structural beauty of this music. Like examining the foundation of a building, observe how the melody dances above the stable bass.

Second, I recommend comparing different versions. Listening alternately to the original string ensemble version and the “Air on the G String” version shows how the same melody can evoke different emotions depending on the instrumentation. Recently, there are many versions performed with historically informed practice, offering the pleasure of discovering performances closer to Bach’s intended sound.

Third, believe in the value of repeated listening. This music reveals new aspects with each hearing. Some days, the elegant melody of the first violin stands out; other days, the subtle middle voice of the viola; and on yet other days, the overall harmonic flow feels especially moving. Like conversation with a good friend, each meeting brings new stories to share.

A Journey of Minutes Containing Eternity

Bach’s “Air” demonstrates the paradox of time. Though only 4-5 minutes long, it contains eternity within. The flow of melody that seems to have no beginning or end, harmonic colors that repeat yet constantly change, emotional layers that appear simple yet are infinitely deep.

Listening to this music, I often realize that true beauty doesn’t lie in complexity. The simplest things sometimes give the deepest resonance. A few dots that Bach drew on staff paper 300 years ago still move our hearts today.

What remains after the music ends? Perfect silence. But even in that silence, the melody continues to flow. In our hearts, in our memories, and until the next moment we meet this music again. Thus Bach’s “Air” continues to sing eternally, transcending time.

Next Destination: Satie’s Gymnopédie No. 3

If Bach’s “Air” demonstrates the perfect balance of the Baroque era, Erik Satie’s Gymnopédie No. 3 presents the starting point of modern minimalism. Despite 200 years between them, both works share a remarkable commonality: “restrained beauty.”

Satie’s Gymnopédie No. 3, in complete contrast to Bach’s string ensemble, is performed by a solitary piano alone. Yet within that lonely resonance, we discover the same depth as in Bach. If Bach’s “Air” is like warm afternoon sunlight, Satie’s Gymnopédie feels like quiet dawn mist.

I recommend listening to both works in succession. A journey from Baroque’s intricate counterpoint to Impressionism’s dreamlike harmony—within this, you can encounter the essence of music that transcends time.