Table of Contents

A Language Beyond Language: Music That Speaks Through Melody Alone

Some music speaks most eloquently when it has no words at all. Rachmaninoff’s “Vocalise” is precisely such a work. Composed to be sung without lyrics—only pure melody—this piece transcends the limitations of language and reaches directly into the deepest chambers of our hearts.

I still remember the first time I heard this piece. Without any explanation, without any narrative, the melody flowed forth and touched something within me—like a forgotten memory suddenly returning. Was it sadness? Longing? Or perhaps something beyond words entirely: beauty itself.

In this guide, we’ll explore the world of Vocalise as it appears in various instrumental guises. We’ll discover how the same melody takes on entirely different colors when played on piano, cello, violin, or by a full orchestra. Within these subtle differences lies the true beauty of this remarkable composition.

1912: The Birth of a Wordless Song

The year 1912 was a pivotal moment in Rachmaninoff’s creative life. Having emerged from a period of crippling depression and self-doubt, he had reached the zenith of his compositional maturity. He placed this special work as the final piece in his song cycle 14 Romances, Op. 34.

Originally written for soprano and piano, the piece instructs the vocalist to sing only on vowels—”ah” or “oo”—rather than actual words. This was a radical departure for its time. In the Russian Romantic tradition, art songs were intimate marriages of poetry and music. Rachmaninoff boldly eliminated the poetry.

Yet remarkably, this “absence” became the work’s greatest strength. Where language vanished, pure emotion remained. And this simplicity made Vocalise infinitely adaptable—the composer himself created an orchestral version, while his students and later musicians transcribed it for cello, violin, flute, and even jazz ensembles.

The structure is beautifully simple: a single-movement piece in ABA form, beginning in E-flat major. A lyrical theme is presented, the middle section shifts to minor and builds emotional intensity, then the opening theme returns in a peaceful resolution. Yet within this simple framework lies an emotional depth anything but simple.

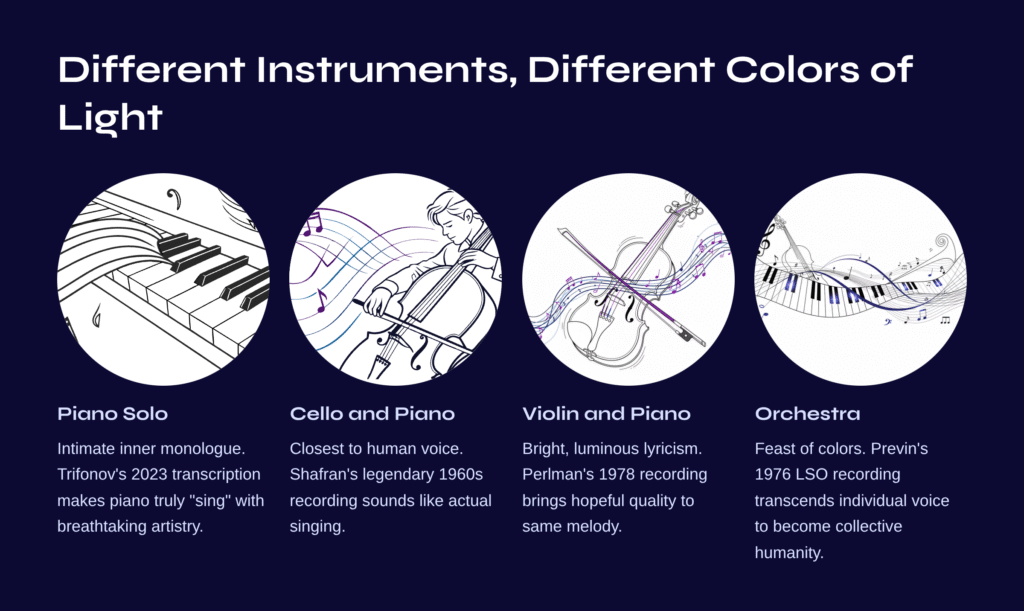

Different Instruments, Different Colors of Light

Few pieces demonstrate as clearly as Vocalise how the same melody can evoke entirely different emotions depending on which instrument plays it. Comparing various versions isn’t merely listening—it becomes a genuine musical adventure.

Piano Solo: An Intimate Inner Monologue

Daniil Trifonov’s 2023 piano transcription caused quite a stir in the classical world. In his hands, Vocalise becomes an intimate soliloquy. The resonance created through pedaling, the subtle gradations of touch—his technique makes the piano truly “sing” the vocal line with breathtaking artistry.

Pay special attention to how the recurring theme receives slightly different colorations with each return. The same notes, yet sometimes they ring clear and transparent, other times heavy and introspective. This is the piano’s unique magic: the most personal of instruments, revealing the performer’s inner landscape most directly.

Cello and Piano: The Voice Closest to Human Song

Of all instruments, the cello approaches the human voice most closely. Daniil Shafran’s 1960s recording proves this definitively. A legend of the Russian cello school, his performance sounds as if someone is actually singing. The trembling vibrato, even the subtle friction of bow against string—all become integral parts of the music.

Gautier Capuçon’s 2020 recording with Nikolai Lugansky offers a more contemporary perspective. Transparent, crystalline sound, restrained emotional expression—yet when the cello’s passion erupts at the climax, it’s utterly heart-wrenching. The piano accompaniment, too, isn’t mere background but another voice in dialogue with the cello.

Comparing these two versions is fascinating. If Shafran’s playing evokes a rich Russian autumn, Capuçon’s suggests a clear winter morning. Same melody, different worlds.

Violin and Piano: Bright, Luminous Lyricism

Itzhak Perlman’s 1978 recording stands as a classic among violin versions. Playing an octave higher than the cello, the violin brings a brighter, more hopeful quality to the same melody. Perlman’s characteristically warm, generous vibrato adds even deeper emotional layers.

The dramatic transition to minor in the middle section proves particularly striking. The violin’s upper register truly shines in these passionate moments, like suppressed emotions suddenly released in a torrent.

Orchestra: A Feast of Colors

André Previn’s 1976 recording with the London Symphony Orchestra remains one of the most beloved orchestral interpretations. When an entire orchestra sings a single melody, it transcends individual voice to become something collective—perhaps the voice of humanity itself.

The lush harmonic waves of the string section, lyrical woodwind lines floating above, the majesty added by brass at the climax—an entire spectrum of sound impossible for any solo instrument unfolds before us.

The moment near the end when the full orchestra plays pianissimo as the theme returns defies description. Dozens of musicians breathing as one, creating such delicate resonance—in that moment, we realize music is more than sound; it’s a kind of miracle.

A Journey Through the Melody

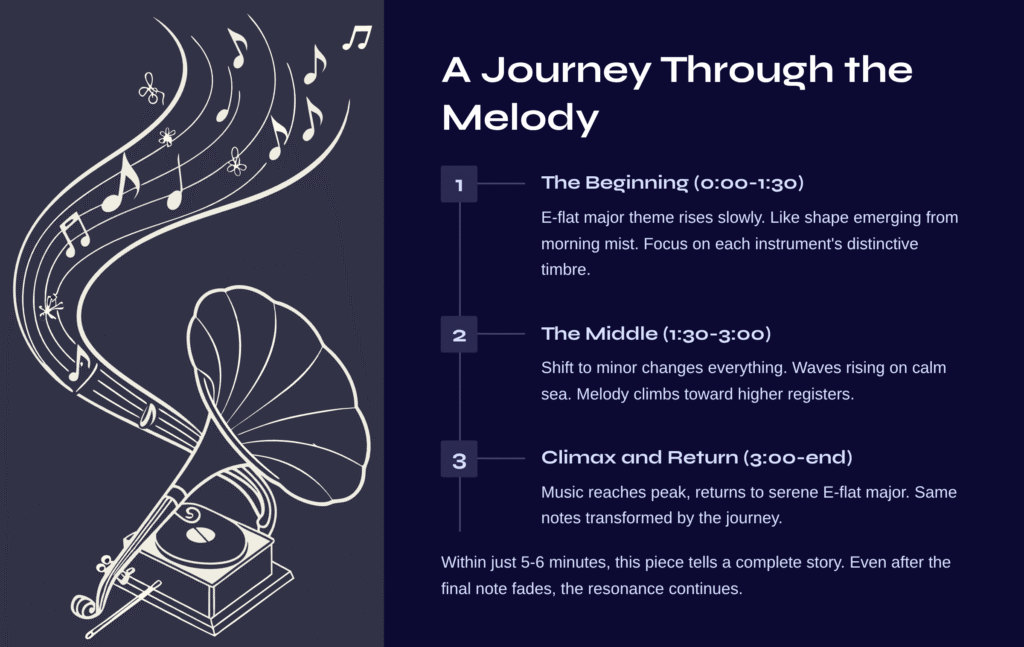

To truly appreciate Vocalise, it helps to understand how the melody unfolds. Within just 5-6 minutes, this piece tells a complete story.

The Beginning: A Song Quietly Blooming (0:00-1:30)

The E-flat major theme rises slowly from a lower register, like a shape gradually emerging from morning mist. Here, focus on each instrument’s distinctive timbre: the piano’s clear percussive tone, the cello’s warm bass, the violin’s transparent treble, the orchestra’s gentle string ensemble. Same melody, entirely different textures.

Notice too the resonance created by pedaling (piano) or vibrato (strings). Even the silences between notes carry meaning.

The Middle: Waves of Emotion (1:30-3:00)

The shift to minor changes everything. Like waves beginning to rise on a calm sea, the melody climbs toward higher registers, dynamics intensify.

In cello and violin versions, this dramatic contrast emerges especially vividly. Breathing deepens, bow pressure increases—you can feel the performer’s entire body drawn into the music.

In the orchestral version, notice the string tremolo and the color contrasts between woodwinds and brass. The layering as different sections alternate or combine creates remarkable sonic architecture.

Climax and Return: From the Heights Back to the Beginning (3:00-end)

The music reaches its peak. Everything condenses at the highest point, then returns to the serene E-flat major theme. But it’s not the same anymore. Having experienced the journey, we hear these familiar notes transformed.

In solo piano, the brilliance of the climax contrasts starkly with the transparent resonance of the ending. In ensemble versions, it’s fascinating to compare how different parts balance and merge as the theme returns.

Even after the final note fades, the resonance continues. Perhaps that silence is the piece’s truest message.

Finding Your Own Vocalise

Listening to this piece repeatedly, I’ve come to understand one truth: there is no “best performance.” Each version possesses its own beauty, speaking differently depending on when and how we listen.

On tired evenings, when I need solitude, I turn to Trifonov’s piano solo. Its delicate, intimate sound becomes a transparent membrane protecting me from the world’s complexity.

When missing someone, caught in emotions beyond words, I listen to Shafran’s cello. Those deep, warm tones comfort me like a hand on my shoulder.

When seeking hope, needing courage to move forward, Perlman’s violin gives me strength. Its bright, warm timbre reminds me that light exists even in darkness.

And sometimes, when I want to feel all the world’s beauty at once, I listen to Previn’s orchestral version. Before that vast ocean of sound, I feel both how small I am and how connected to something immeasurably beautiful.

Tips for Deeper Listening

The Joy of Comparative Listening

Don’t hesitate to play different versions back-to-back. That’s when music’s essence reveals itself most clearly. Listen to Trifonov’s piano immediately followed by Shafran’s cello, and you’ll be amazed at how differently the same melody can be expressed.

Listen Softly

Vocalise doesn’t need to be played loudly. In fact, its delicacy emerges most beautifully at low volume. Especially with the piano solo—listen almost at a whisper. The spaces between notes, the subtle resonance of the pedal, the changes in touch—all speak like confidences shared in your ear.

The Value of Repetition

This isn’t music that reveals itself in one hearing. The more you listen, the more you discover. First time, you notice the melody. Second or third, you hear harmonic shifts. Then the accompaniment’s details emerge. Eventually, you stop “listening” to the music—you begin experiencing it.

A Melody That Transcends Time

Born in 1912, this small piece has traveled across more than a century to speak to us still. Having no lyrics, it knows no language barriers. Unbound to any specific era or culture, it communicates through pure melody alone.

What did Rachmaninoff want to say through this piece? Perhaps he wanted to say nothing at all—not with words, anyway. Instead, he wanted us to feel, interpret, and find consolation in our own ways.

Some days this music sounds like sorrow. Other days it brings profound peace. Sometimes it’s nostalgia; sometimes hope. And all of these are correct. Because music doesn’t provide answers—it awakens something within us.

Next time you have a chance to hear Vocalise, I encourage you to find your preferred version—piano, cello, violin, or orchestra. Then listen carefully to what resonance it creates within you.

What does this wordless song whisper to you?

Next Journey: Grieg’s Nocturnal Melody

If the echoes of Vocalise still linger, the Nordic lyric poet Edvard Grieg awaits you. His “Notturno (Night Song)” from Lyric Pieces, Op. 54 No. 4 offers something different from Rachmaninoff’s Slavic melancholy—a clear, transparent Nordic lyricism.

Grieg’s Notturno is a small nocturne for solo piano, yet it contains Norwegian summer nights: the midnight sun that never sets, the quiet ripples of fjords, whispers of nature from deep forests. If Vocalise is a “wordless song,” Grieg’s Notturno is a “landscape painted in notes.”

After experiencing Rachmaninoff’s deep emotional currents, entering Grieg’s transparent, lyrical world creates a fascinating contrast. Two composers who lived in the same Romantic era yet inhabited completely different emotional universes. Through their music, you’ll experience the rich diversity of European classical tradition.