📑 Table of Contents

You’ve heard it before. Maybe at a cousin’s wedding, drifting through the doors of an old stone church. Perhaps in a film, right before something quietly miraculous happens. That gently flowing melody, unhurried and luminous, weaving through the air like a silk ribbon carried by the wind.

But here’s what most people don’t know: Johann Sebastian Bach never intended this piece for weddings at all.

The Man Behind the Music

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) was, in many ways, a man out of step with fame. During his lifetime, he was known primarily as an exceptional organist, not as the towering compositional genius we recognize today. He spent much of his career as a church musician in Leipzig, Germany, churning out cantatas week after week for Sunday services—a workload that would exhaust most modern composers.

Bach wasn’t composing for concert halls or aristocratic applause. He was writing for God, for ordinary congregants, for the rhythm of the liturgical calendar. And yet, within these “functional” works, he created some of the most sublime music humanity has ever known.

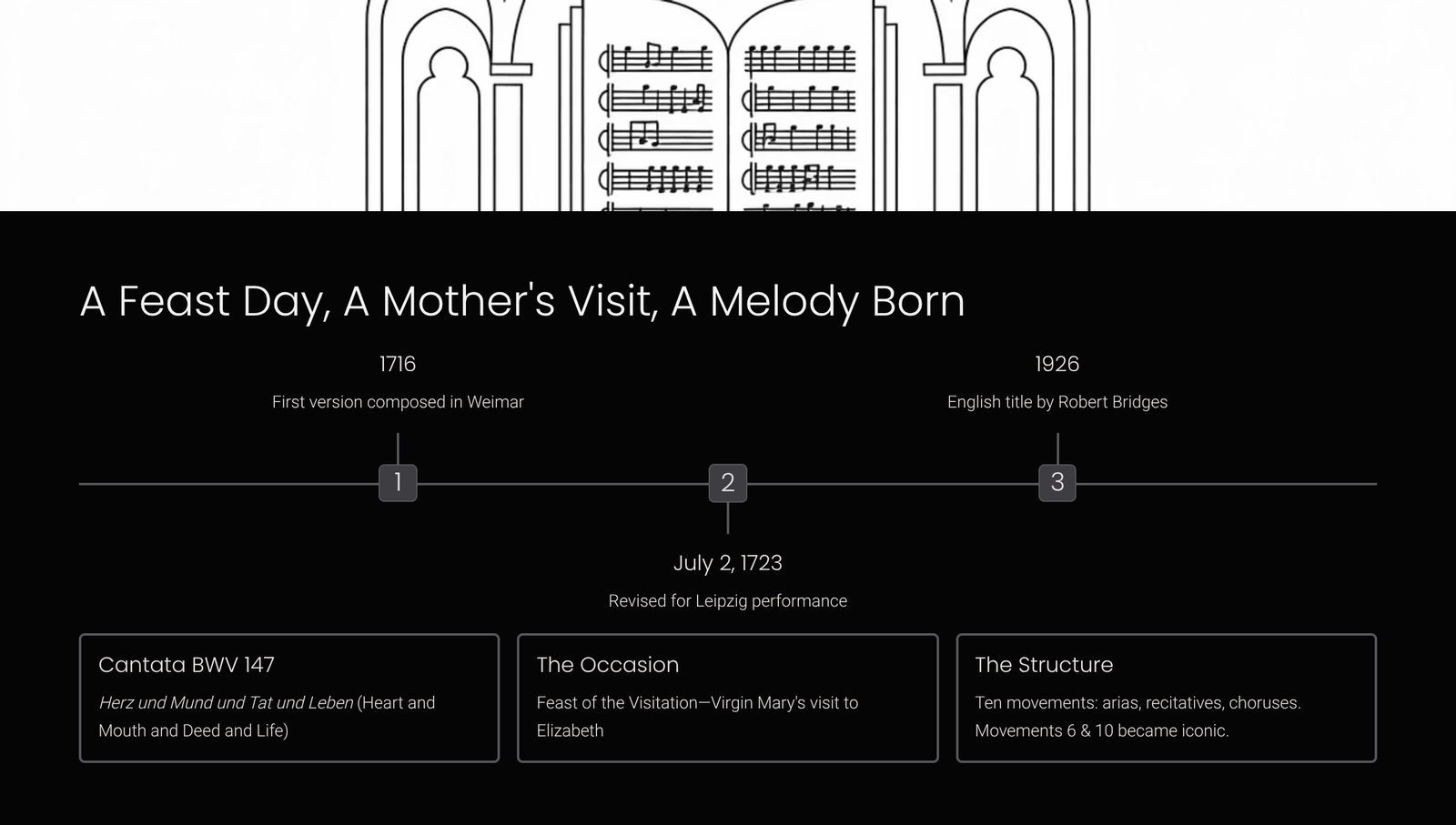

A Feast Day, A Mother’s Visit, A Melody Born

Cantata BWV 147, titled Herz und Mund und Tat und Leben (Heart and Mouth and Deed and Life), was composed for the Feast of the Visitation—a Christian holiday commemorating the Virgin Mary’s visit to her cousin Elizabeth. Bach first wrote an earlier version in Weimar around 1716, then revised and expanded it for performance in Leipzig on July 2, 1723.

The cantata contains ten movements: arias, recitatives, and choruses that meditate on faith, devotion, and the expression of belief through action. But it’s the sixth and tenth movements—both settings of the same chorale melody—that would eventually escape their liturgical origins and take on a life of their own.

The English title “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring” comes from a 1926 translation of the original German hymn text by poet Robert Bridges. The melody itself, that cascading triplet figure we all recognize, isn’t even Bach’s invention—it’s his ingenious instrumental accompaniment layered over a pre-existing Lutheran chorale tune.

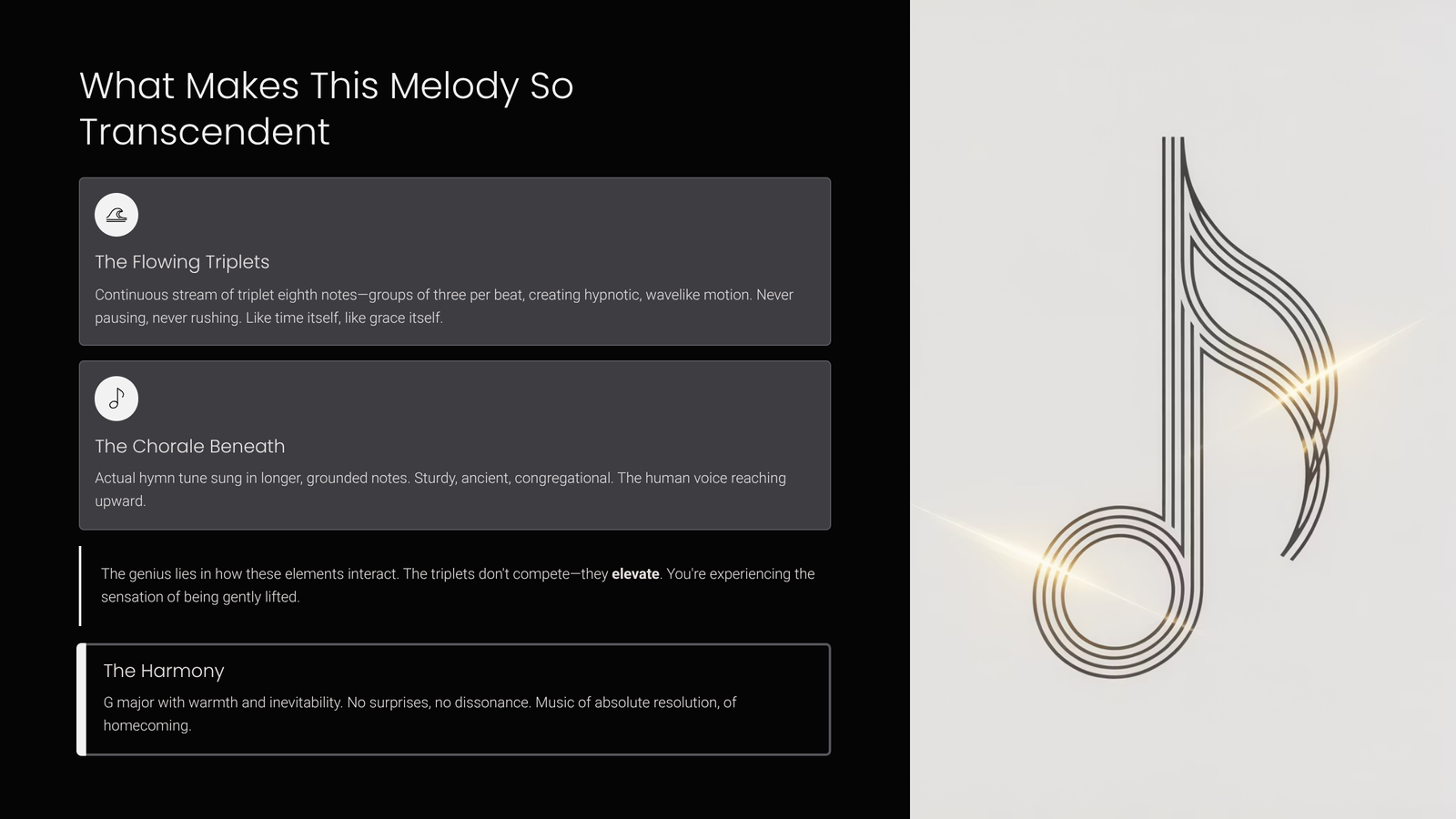

What Makes This Melody So Transcendent

Listen closely, and you’ll notice something remarkable about the structure. The piece operates on two distinct planes simultaneously.

The flowing triplets: Above everything floats that continuous stream of triplet eighth notes—groups of three notes per beat, creating an almost hypnotic, wavelike motion. This isn’t the main melody; it’s the atmosphere, the air through which the hymn breathes. These triplets never pause, never rush. They simply continue, like time itself, like grace itself.

The chorale beneath: Underneath this shimmering surface moves the actual hymn tune, sung by the choir in longer, more grounded notes. This melody is sturdy, ancient, congregational. It’s the human voice reaching upward.

The genius lies in how these two elements interact. The triplets don’t compete with the chorale—they elevate it. They transform a simple hymn into something that feels like ascension. You’re not just hearing music; you’re experiencing the sensation of being gently lifted.

The harmony, too, deserves attention. Bach moves through the key of G major with warmth and inevitability, each chord change arriving exactly when your ear hopes it will. There are no surprises here, no dissonance to disturb the peace. This is music of absolute resolution, of homecoming.

Why Weddings Claimed It

So how did a church cantata movement become synonymous with brides walking down the aisle?

The answer lies partly in early 20th-century arrangements. British pianist Myra Hess created a famous piano transcription in 1926, the same year Robert Bridges published his English translation. Suddenly, the piece was accessible outside of church choirs and Baroque ensembles. It could be played on a single piano, in a living room, at a ceremony.

And the music itself practically demands ritual. That unhurried pace, that sense of procession, that feeling of something sacred unfolding—it mirrors the emotional cadence of a wedding perfectly. The melody doesn’t celebrate with fireworks; it sanctifies with stillness.

There’s also something deeply human about its structure. The repeating triplet pattern creates a sense of continuity, of life going on. The chorale melody provides the moment of focus, the vow, the commitment. Together, they suggest that love is both eternal flow and deliberate choice.

How to Listen with Fresh Ears

If you’ve heard this piece a hundred times at weddings, try approaching it differently.

First, listen in its original context. Find a recording of the complete Cantata BWV 147. Hear how “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring” appears twice—once in the middle, once at the end—bookending the work’s theological journey. In context, it’s not just pretty music; it’s a statement of faith, a resolution.

Second, focus on the bass line. Bach’s bass parts are never mere accompaniment. Follow the lowest voice and you’ll discover a walking, purposeful progression that gives the floating triplets their grounding.

Third, close your eyes and breathe with it. The tempo of this piece aligns remarkably well with calm, meditative breathing. Let the music set your rhythm. This is how congregants in 1723 might have experienced it—not as a performance, but as a prayer made audible.

Recordings Worth Your Time

For a historically informed performance on period instruments, the Monteverdi Choir and English Baroque Soloists under John Eliot Gardiner offer clarity and devotion in equal measure. Their recording captures the transparency Bach likely intended.

If you prefer the piano transcription, Dinu Lipatti’s 1950 recording remains legendary—tender, unhurried, and profoundly moving. It’s the version that introduced many 20th-century listeners to the piece.

For a full orchestral treatment, Karl Richter with the Munich Bach Orchestra brings a weightier, more Romantic interpretation. It’s less “authentic” but deeply emotional.

And for something unexpected, seek out Jacques Loussier’s jazz trio version. Hearing those sacred triplets swing with brushed drums and upright bass reveals just how adaptable Bach’s architecture truly is.

A Melody That Found Its Purpose

Bach composed Cantata BWV 147 for a single feast day in a single German city over 300 years ago. He probably assumed it would be performed a few times, appreciated by the faithful, then filed away in the church archives.

He couldn’t have known that one movement—ten minutes of music written to glorify divine love—would become the soundtrack to human love at its most ceremonial moment.

Perhaps that’s the final lesson of “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring.” Great art doesn’t always know its own destiny. Sometimes a melody has to wait centuries to find the hearts it was truly meant for.

The next time you hear those triplets begin—at a wedding, in a film, or drifting from a practice room window—remember: you’re not just hearing background music. You’re hearing a prayer that escaped its original altar and found altars everywhere.