📑 Table of Contents

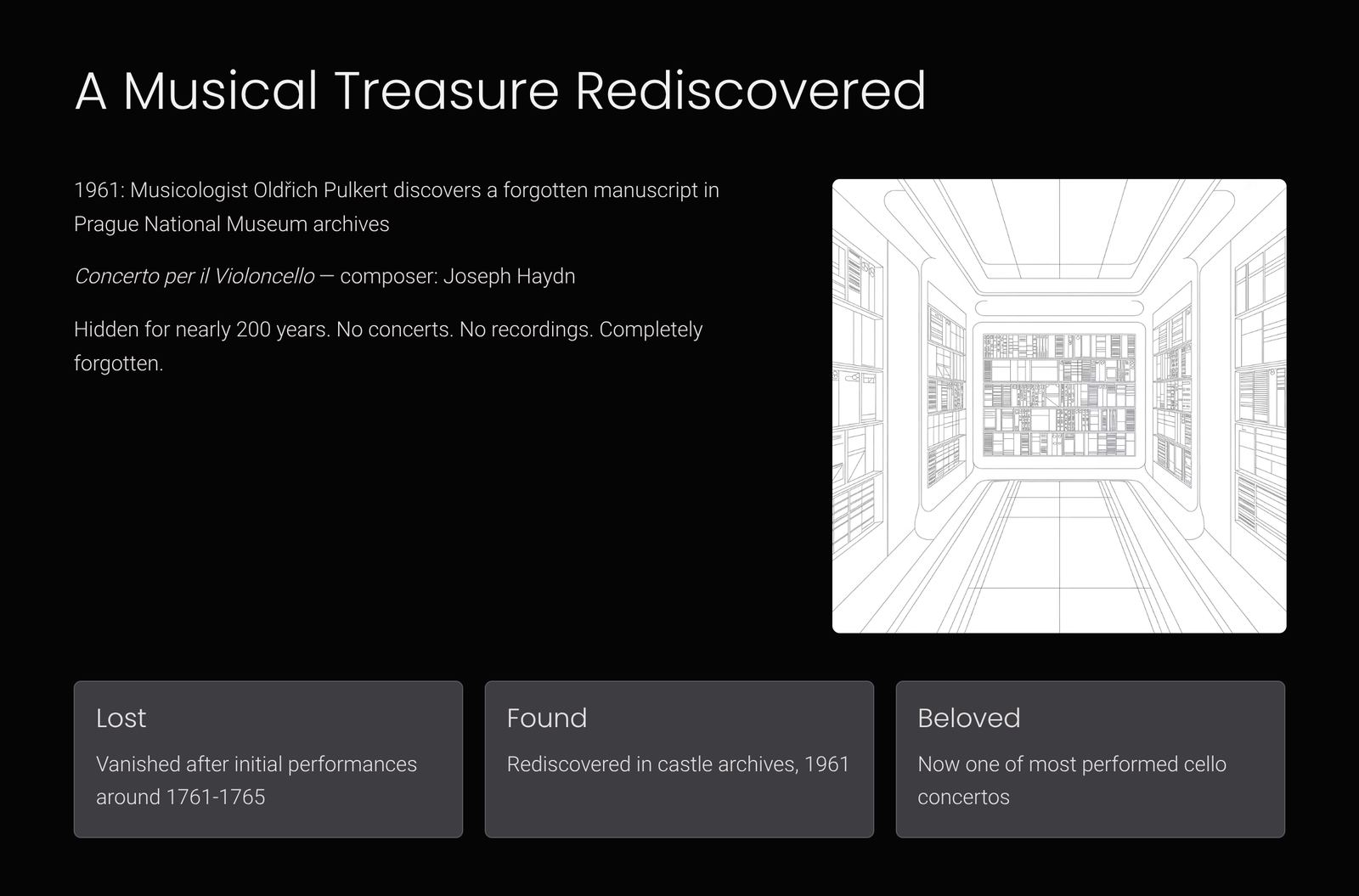

Imagine a piece of music so beautiful, so perfectly crafted, yet completely forgotten for nearly two hundred years. No concerts. No recordings. Not even a mention in music history books. Then, in 1961, a musicologist named Oldřich Pulkert was sifting through dusty archives in the Prague National Museum when he stumbled upon a handwritten manuscript. The title read: Concerto per il Violoncello — and the composer’s name was unmistakable: Joseph Haydn.

This is the story of Haydn’s Cello Concerto No. 1 in C major, a work that vanished into obscurity for two centuries before emerging as one of the most beloved cello concertos in the repertoire. Today, we explore its radiant first movement, the Moderato, and why its rediscovery feels like finding a lost letter from an old friend.

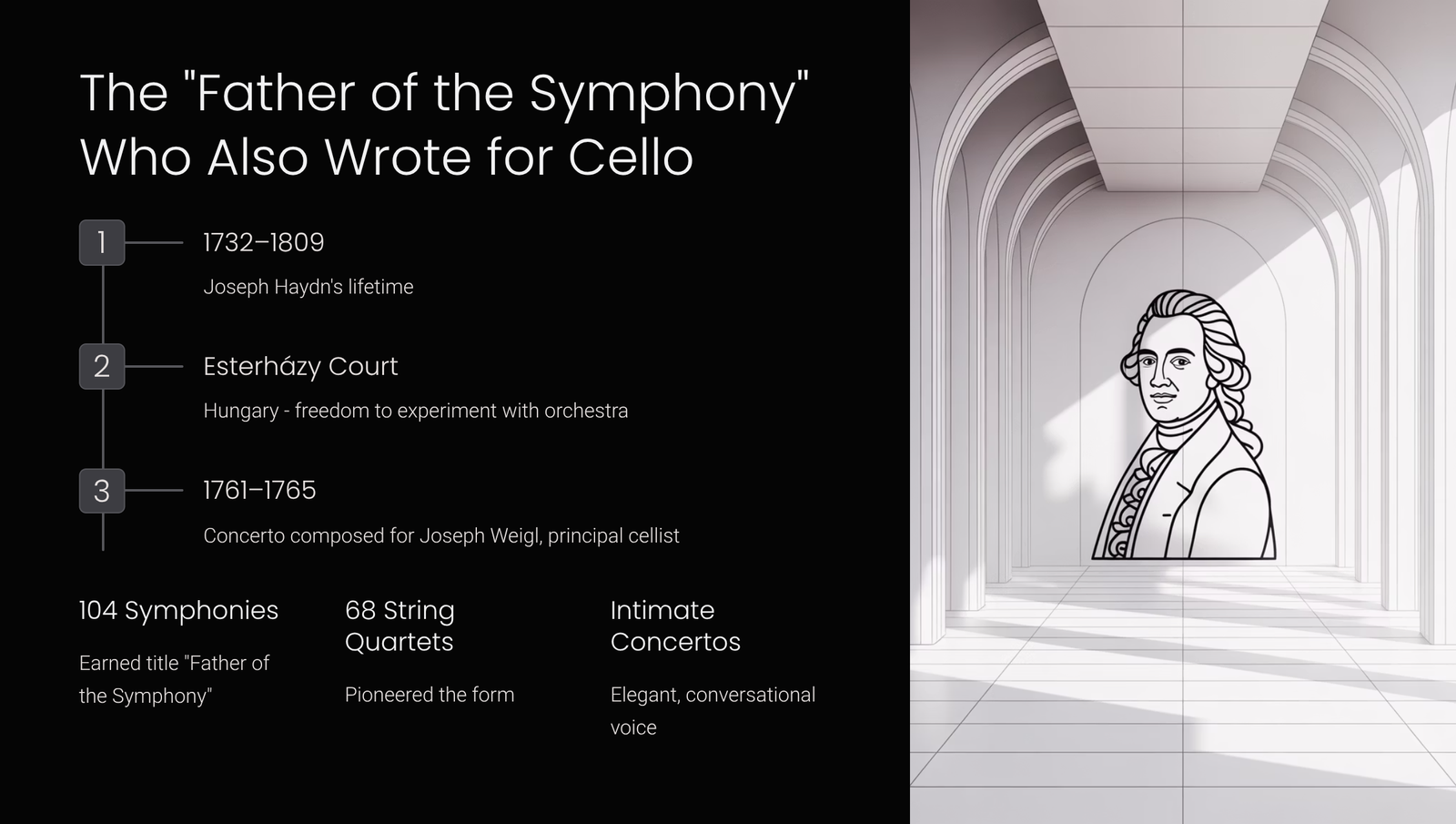

The “Father of the Symphony” Who Also Wrote for Cello

Joseph Haydn (1732–1809) is often called the “Father of the Symphony” and the “Father of the String Quartet.” He spent most of his career at the Esterházy court in Hungary, where he had an orchestra at his disposal and the freedom to experiment. While his 104 symphonies and 68 string quartets dominate his legacy, his concertos reveal a more intimate side of his genius.

The Cello Concerto No. 1 was likely composed around 1761–1765, during Haydn’s early years at Esterházy. Scholars believe he wrote it for Joseph Weigl, the principal cellist of the court orchestra. Unlike the virtuosic fireworks of later Romantic concertos, this work showcases the cello as a singing, graceful voice — elegant rather than flashy, conversational rather than confrontational.

Why Did It Disappear?

Here’s the mystery: after its initial performances, the concerto simply vanished. No published editions. No copies circulating among musicians. It wasn’t performed, studied, or even remembered. For nearly 200 years, music lovers had no idea this gem existed.

The 1961 rediscovery changed everything. Once authenticated and published, the concerto quickly entered the standard repertoire. Cellists finally had another major Classical-era concerto to pair with Haydn’s more famous No. 2 in D major. The musical world gained a treasure it never knew it had lost.

Listening to the First Movement: Moderato

The first movement opens with the orchestra stating a cheerful, striding theme in C major. There’s an unmistakable optimism here — Haydn at his most confident and sunlit. When the solo cello enters, it doesn’t try to overpower the orchestra. Instead, it joins the conversation, adding its warm, woody voice to the dialogue.

Here’s what to listen for:

The Opening Theme: Pay attention to how the melody bounces with a gentle, almost dance-like rhythm. Haydn was a master of making simple ideas feel endlessly fresh.

The Cello’s Entrance: Notice how the soloist seems to emerge naturally from the orchestral texture, as if the cello had been there all along, just waiting for its turn to speak.

The Development Section: Haydn takes his themes through different keys and moods, but never loses the movement’s essential brightness. Even in minor-key passages, there’s a sense of play rather than drama.

The Cadenza: Most performances include a cadenza — a moment where the orchestra pauses and the soloist improvises or plays a written-out solo passage. Listen for how different cellists approach this moment. Some keep it elegant and Classical; others add Romantic flourishes.

Recommended Performances

If you’re new to this concerto, here are some recordings worth exploring:

Mstislav Rostropovich with the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields delivers a performance that balances Classical restraint with emotional depth. His tone is rich and singing, never forced.

Jacqueline du Pré recorded this concerto with a youthful intensity that feels both historically informed and deeply personal. Her version crackles with energy.

Yo-Yo Ma offers a polished, lyrical interpretation that emphasizes the concerto’s songfulness. Perfect for a relaxed listening session.

Sol Gabetta brings a modern sensibility to the work, with crisp articulation and vibrant orchestral partnership.

Each cellist finds something different in this music. That’s part of its magic — Haydn’s score is generous enough to accommodate many voices.

Why This Music Still Matters

There’s something poignant about listening to music that was lost and found. When you hear those opening bars, you’re hearing something that audiences in 1800, 1850, 1900, and 1950 never got to experience. The concerto slept while the world changed — revolutions, wars, the invention of recording technology — and then woke up, as fresh and vital as the day it was written.

Haydn couldn’t have known his manuscript would survive neglect and time. He simply wrote the best music he could for a cellist he admired. Two centuries later, that music found its way back to us.

Perhaps that’s the most hopeful thing about art: it waits. It endures. And when we finally discover it — or rediscover it — it feels less like archaeology and more like reunion.

Press play. Let the cello sing. And welcome back a masterpiece that was always meant to be heard.