📑 Table of Contents

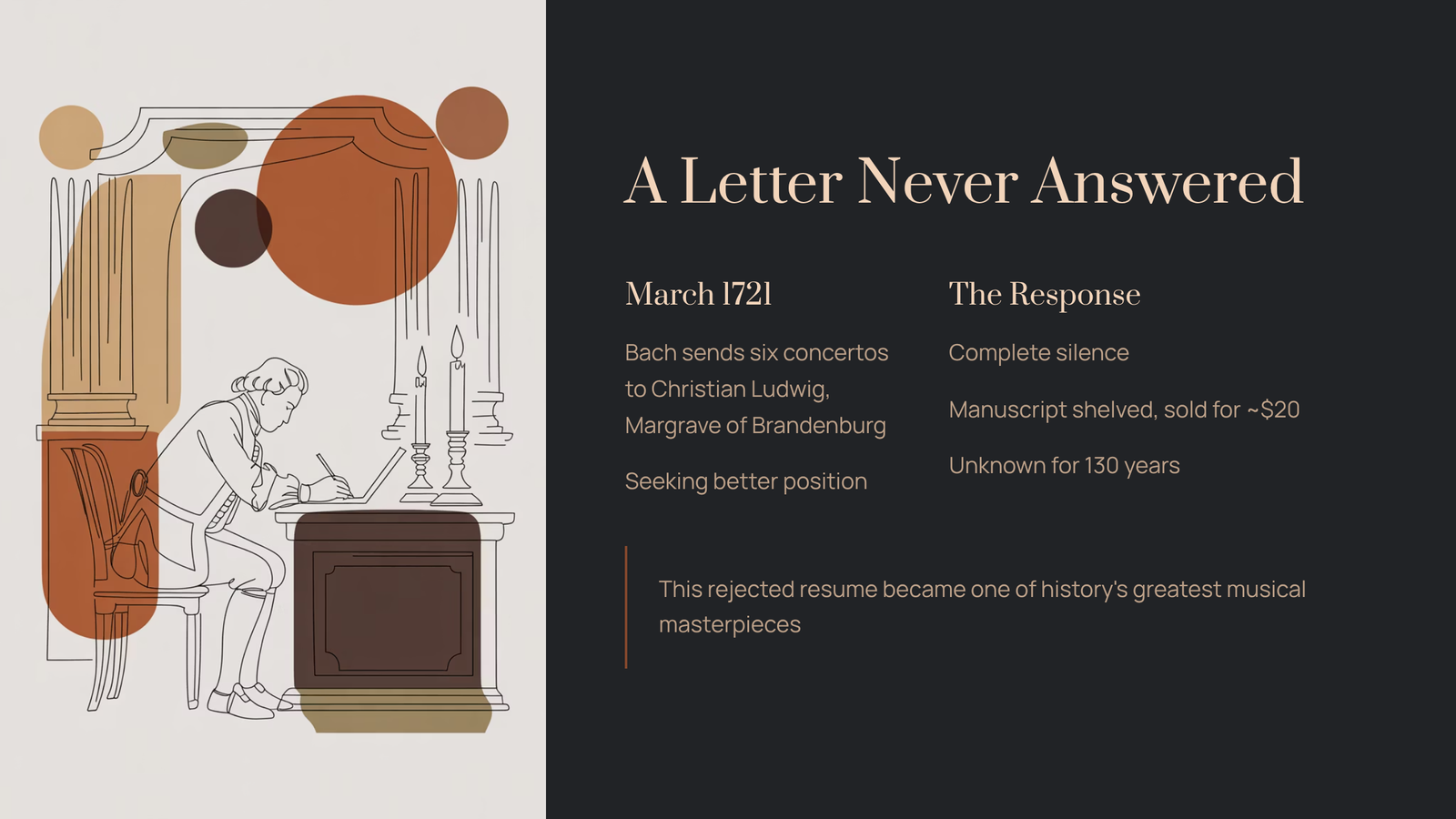

Picture this: It’s March 1721. Johann Sebastian Bach, then working as a court musician in the small German town of Köthen, carefully prepares a beautifully handwritten manuscript. Six concertos, representing years of his finest instrumental work. He sends them to Christian Ludwig, Margrave of Brandenburg—a nobleman who might offer him a better position.

The Margrave receives the package. He never writes back. Not a single word of thanks, no job offer, nothing. The manuscript gets shelved, eventually sold for the equivalent of about twenty dollars, and remains virtually unknown for the next 130 years.

This is the origin story of the Brandenburg Concertos—and among them, the Third Concerto stands as perhaps the most ingeniously constructed piece Bach ever wrote for strings alone.

The Accidental Masterpiece

What makes the Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 so special isn’t just its beauty—it’s its audacious design. Bach assembled nine string players (three violins, three violas, three cellos) plus harpsichord, and then did something revolutionary: he made every single player a soloist.

In most concertos of the Baroque era, you had a clear division. Solo instruments stepped forward to shine, while the orchestra provided support. Bach threw that rulebook away. Here, all nine voices constantly weave in and out, trading melodies, answering each other, creating what one writer called “exuberant dialogue” between instrumental families.

The result sounds far larger than a chamber ensemble. It’s like watching a perfectly choreographed conversation where everyone has something brilliant to say, and somehow nobody talks over anyone else.

What You’re Actually Hearing

The first movement—marked simply “Allegro” (though Bach himself never wrote a tempo indication)—opens with all nine strings launching into a confident, galloping theme together. That driving rhythm never really stops. It pushes forward relentlessly, like a machine built from pure musical energy.

But here’s where it gets interesting. After that bold opening statement, the texture suddenly thins. The violins take the theme and run with it. Then the violas pick it up. Then the cellos. It’s like watching a relay race in slow motion, each group passing the musical baton while maintaining that unstoppable momentum.

The harmonic journey is equally fascinating. Bach systematically explores every possible key relationship from the home base of G major. He visits the dominant (D major), the subdominant (C major), touches on minor keys (E minor, B minor, A minor), building an architectural structure that most listeners feel without consciously recognizing.

And then, around three-quarters through the movement, something unexpected happens.

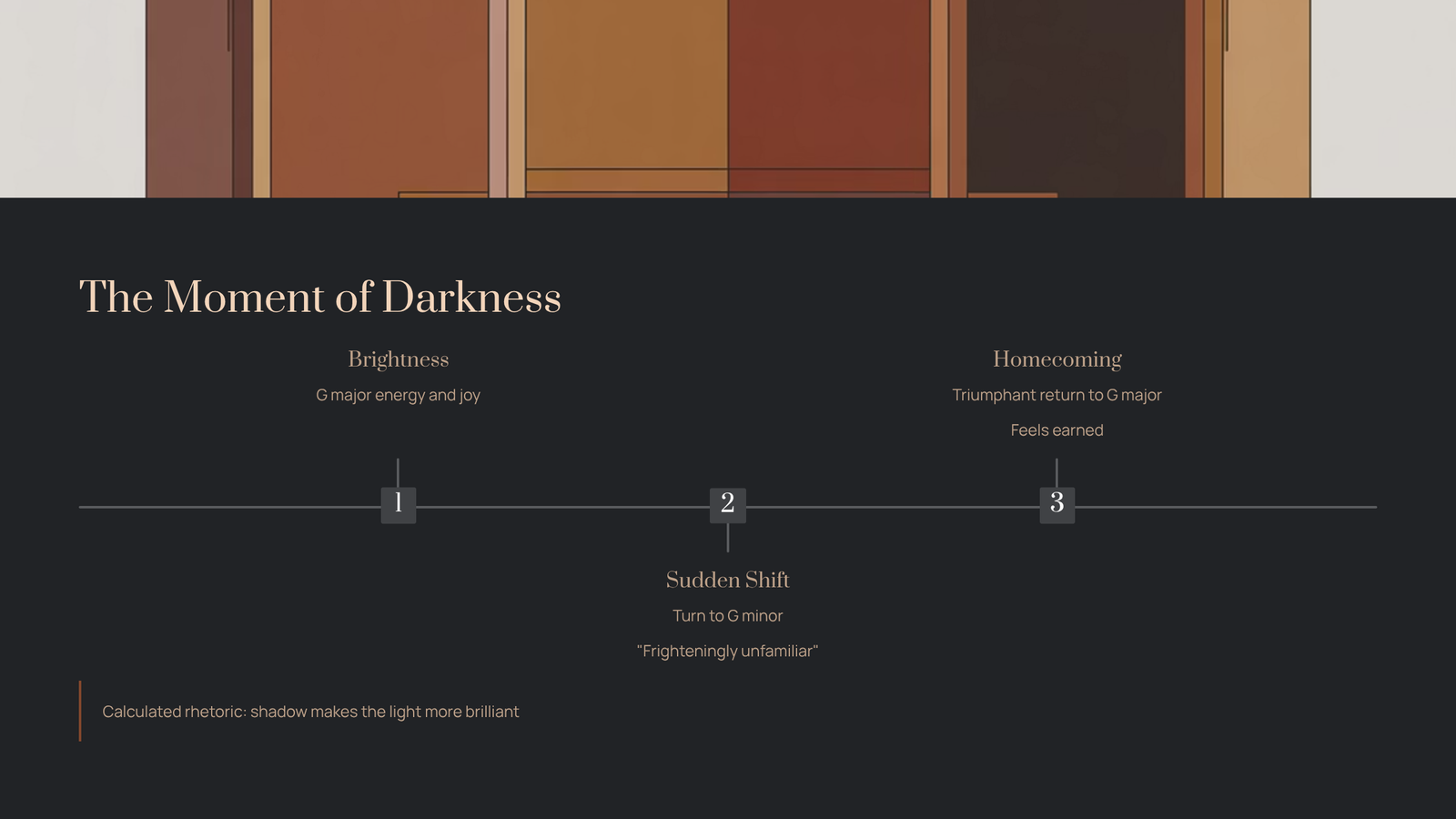

The Moment of Darkness

After all that brightness and energy, Bach suddenly steers the music into G minor—the parallel minor key. It’s brief, lasting only a few measures, but the effect is startling. One music critic described it perfectly: “We turn a harmonic corner and suddenly find ourselves in a frighteningly unfamiliar new place.”

This isn’t random. It’s calculated rhetoric. By introducing that shadow of darkness, Bach makes the triumphant return to G major—when the full opening theme comes back in its original form—feel like a genuine homecoming. You’ve been on a journey. You’ve faced uncertainty. And now you’re back, and it feels earned.

The movement ends exactly as it began, with all nine voices united in that infectious, joyful energy. But you’ve been changed by the experience of listening.

The Math Behind the Magic

Bach loved the number three. The Brandenburg set contains six concertos (two times three). This particular concerto uses three groups of three instruments each. Even the musical structure follows triadic patterns.

This wasn’t mere numerology. In Baroque musical thinking, three represented perfection—a reflection of the Holy Trinity, the complete division of rhythm. Bach embedded this symbolism into the DNA of the piece, creating something that satisfies on a level most listeners can feel but never articulate.

The conductor and Bach scholar John Eliot Gardiner observed that studying this work reveals Bach’s “musical thinking”—his systematic approach to generating complex beauty from simple materials. A single three-note motif (essentially just scale-step-scale-step) generates the entire movement through transformation, inversion, and recombination.

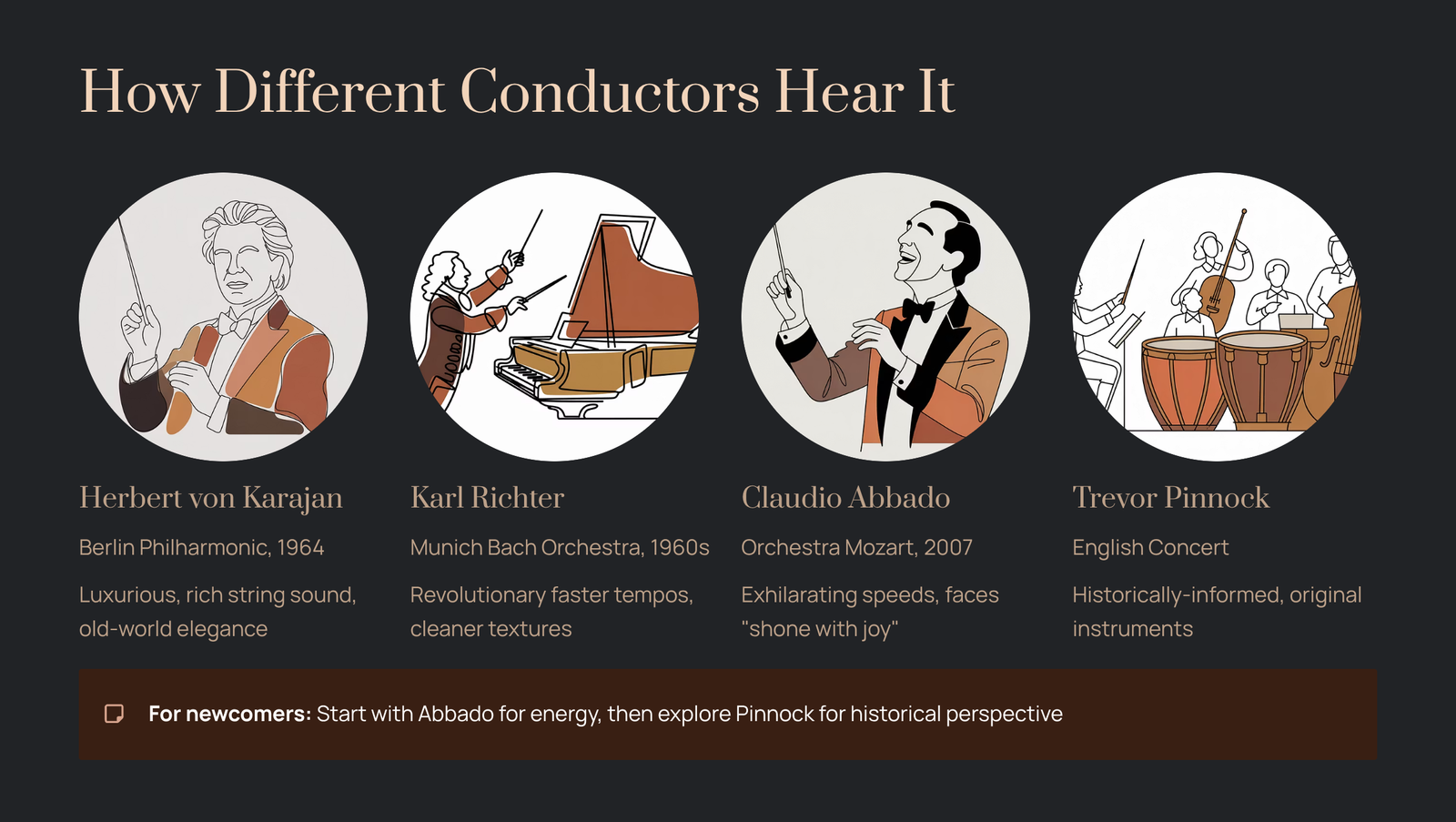

How Different Conductors Hear It

One of the joys of this concerto is hearing how radically different interpretations can be:

Herbert von Karajan (Berlin Philharmonic, 1964) takes a luxurious approach—rich string sound, constantly shifting balances, a certain old-world elegance. It’s like hearing the piece performed in a grand concert hall, even when you’re listening on headphones.

Karl Richter (Munich Bach Orchestra, 1960s) was revolutionary for his time—faster tempos, cleaner textures, a sense of forward drive that influenced everything that came after.

Claudio Abbado (Orchestra Mozart, 2007) pushes the tempo to exhilarating speeds while using period-appropriate instruments. Reviewers noted that the performers’ faces “shone with joy” during recording sessions. That energy translates directly into the listening experience.

Trevor Pinnock (English Concert) represents the historically-informed approach—smaller forces, original instruments, ornamentation that would have been familiar to Bach’s own musicians. It’s a window into what 18th-century listeners might have experienced.

For newcomers, I’d recommend starting with Abbado’s recording for its sheer energy, then exploring Pinnock’s version for historical perspective.

A Second Life in Sacred Music

Eight years after sending his unsuccessful job application, Bach recycled this concerto’s first movement for a church cantata. In 1729, he expanded the orchestration—adding two horns, two oboes, and a tenor oboe to the original strings—and used it as the opening symphony for “Ich liebe den Höchsten von ganzem Gemüte” (I Love the Highest with All My Heart), BWV 174.

Gardiner describes the result as adding “new-minted sheen and force” to the original, with colors and rhythms even sharper than before. It’s a reminder that Bach never stopped developing his ideas, and that great music can find new contexts without losing its essential character.

The Curious Middle Movement

Here’s a quirk that puzzles performers and delights music theorists: the second movement consists of exactly two chords. Just two sustained notes bridging the energetic outer movements.

What’s supposed to happen between those chords? Improvisation. The harpsichordist was expected to fill that silence with a spontaneous cadenza, a moment of personal expression in an otherwise tightly structured work. Modern performers handle this differently—some play brief ornamental passages, others create elaborate fantasias, some simply let the two chords speak for themselves.

It’s a reminder that Baroque music was never meant to be museum pieces. It was living, breathing, partially improvised art.

Why This Music Still Works

The Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 has appeared in everything from Star Trek: The Next Generation (Captain Picard plays it as a duet) to countless study playlists. Its perpetual-motion energy makes it ideal for focus and concentration. Its complex textures reward repeated listening without ever becoming fatiguing.

But beyond utility, there’s something deeply satisfying about this music. It’s the sound of a master craftsman at the height of his powers, creating something both intellectually rigorous and immediately appealing. You don’t need to understand the harmonic architecture to feel its effects. The joy is built into the structure itself.

Bach’s job application failed spectacularly in its original purpose. The Margrave of Brandenburg missed out on hiring one of history’s greatest composers. But that failure preserved these works in a form that eventually reached us—and for that accident of history, we can be grateful.

The next time you hear those nine strings launch into their galloping theme, remember: you’re listening to a rejected resume. And it’s magnificent.

Listening Recommendations

For first-time listeners: Claudio Abbado with Orchestra Mozart (2007) — Energetic, clear, and utterly captivating.

For historical context: Trevor Pinnock with The English Concert — Authentic Baroque sound and ornamentation.

For lush orchestral sound: Herbert von Karajan with Berlin Philharmonic (1964) — Romantic grandeur applied to Baroque architecture.

For scholarly depth: John Eliot Gardiner with English Baroque Soloists — Historically informed yet emotionally immediate.

The movement runs roughly seven minutes depending on tempo choices. Put on good headphones, press play, and let Bach’s nine-voice conversation unfold. You might find yourself hitting repeat.