📑 Table of Contents

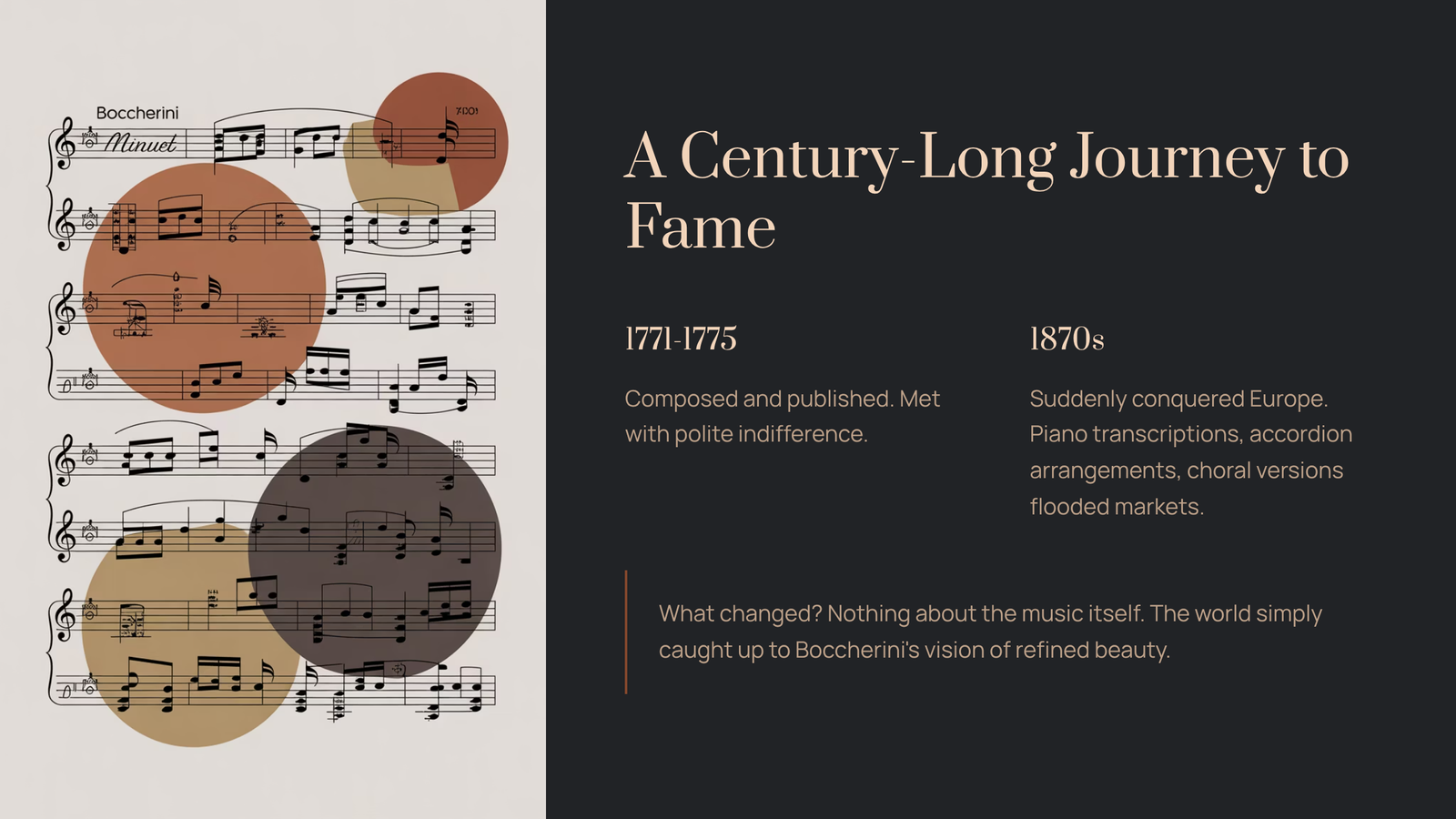

Imagine composing something so elegant, so perfectly crafted, that it takes the world nearly a hundred years to notice. That’s exactly what happened to Luigi Boccherini’s Minuet from his String Quintet in E major. Written in 1771 and published in 1775, this graceful dance was met with polite indifference. Fast forward to the 1870s, and suddenly all of Europe couldn’t get enough of it. Piano transcriptions, accordion arrangements, even choral versions with Latin text flooded the market. It earned a nickname that stuck: “The Celebrated Minuet.”

What changed? Nothing about the music itself. The world simply caught up to Boccherini’s vision of refined beauty.

Who Was Luigi Boccherini?

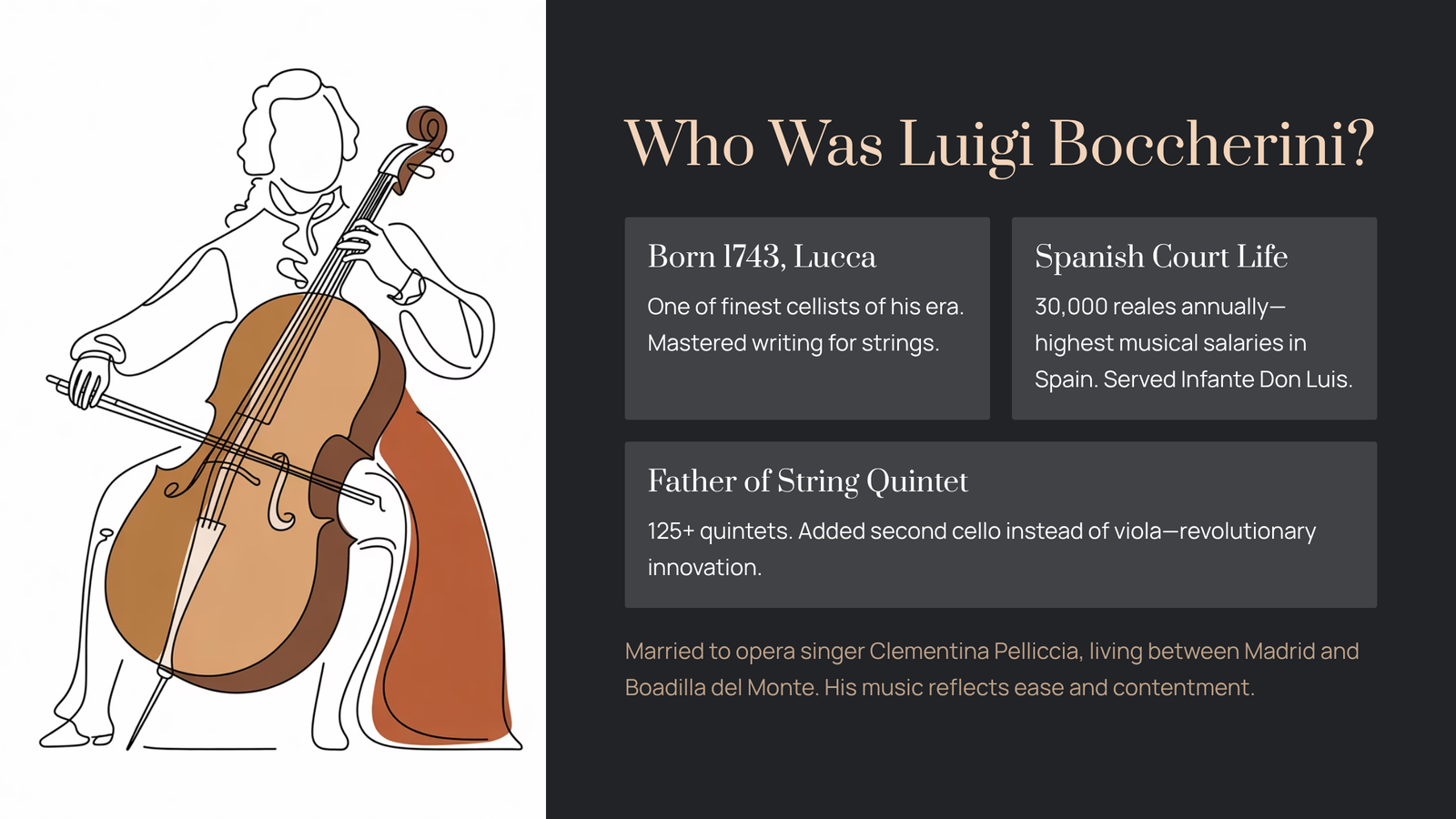

Born in Lucca, Italy in 1743, Luigi Boccherini was one of the finest cellists of his era—and he knew how to write for strings like few others. While his contemporary Haydn was revolutionizing the symphony in Vienna, Boccherini carved out his own territory in Spain, serving as court composer to the Infante Don Luis, brother of King Charles III.

This wasn’t a struggling artist’s life. In 1770, Boccherini landed a dream position paying 30,000 reales annually—one of the highest musical salaries in Spain. He lived between Madrid and the countryside estate at Boadilla del Monte, newly married to Italian opera singer Clementina Pelliccia. Life was good. The music he wrote during this period reflects that sense of ease and contentment.

Boccherini composed over 125 string quintets in his lifetime, earning him the title “father of the string quintet.” His signature innovation? Adding a second cello instead of a second viola. As a virtuoso cellist himself, he understood that freeing one cello from bass duties opened up an entirely new world of sound—the cello could now sing in its highest register, trading melodies with the violins.

What Makes This Minuet Special

The Minuet comes from his String Quintet in E major, Op. 11, No. 5 (catalogued as G.275). It’s the third movement of a four-movement work, and while the entire quintet deserves attention, this particular movement captured something universal.

The structure is deceptively simple: a compound ternary form (ABA), meaning you hear the main minuet, then a contrasting trio section, then the minuet returns. Three-four time, moderate walking pace. Nothing revolutionary on paper.

But listen closely, and you’ll notice what sets Boccherini apart.

The first violin carries a memorable, almost singable melody marked by syncopation—accents landing on unexpected beats. This rhythmic playfulness was actually quite unusual for 18th-century minuets, which typically kept their accents predictable. Boccherini gives you elegance, yes, but with a subtle wink.

Underneath, the viola and two cellos pluck gentle pizzicato notes—short, detached sounds that create a delicate rhythmic bed. This light accompaniment is one of the movement’s most distinctive features. It sounds almost like a musical jewelry box, each note precisely placed.

Meanwhile, the second violin has a deceptively demanding part: rapid sixteenth-note figures requiring constant string crossings. As musicologist Elisabeth Le Guin noted, the second violinist has no time for elegance—they’re too busy managing technical challenges that remain invisible to the listener. The effort is hidden; only the grace shows.

Listening Guide: What to Notice

Opening (Minuet section): Pay attention to how the first violin’s melody seems to float above the pizzicato accompaniment. Notice those unexpected accents—they give the music a gentle forward momentum, like a dancer making small improvisations within the formal steps of a court dance.

The Trio: When the middle section arrives, the texture changes. The music moves through F major and touches on F minor, adding a subtle shadow to the brightness. All the instruments move together more closely here, creating a more unified sound. It’s a brief detour into a slightly different emotional territory before returning home.

The Return: When the minuet comes back, you’ll hear it with fresh ears. Details you missed the first time—the interplay between voices, the technical precision of the second violin, the perfect placement of those pizzicato notes—become clearer.

The entire movement takes only about four minutes. It asks nothing of you except your attention.

The Sensibilité Factor

To fully appreciate this music, it helps to understand the aesthetic concept that shaped Boccherini’s world: sensibilité. This French term, popular among 18th-century aristocrats, described a refined emotional sensitivity—the ability to be moved by beauty, to feel deeply without dramatic display.

Boccherini’s music embodies this ideal perfectly. He was known for his “obsession with soft dynamics,” his love of extended passages of beautiful texture, and what Le Guin calls “an extraordinary rich palette of introverted and melancholic sentiments.” Even in a cheerful minuet, there’s an intimacy, a sense that this music was meant for a small room and attentive listeners.

This wasn’t music for grand public concerts. It was chamber music in the truest sense—music for a chamber, a private room, shared among friends.

From Obscurity to Hollywood

The minuet’s modern fame owes much to the 1955 British comedy “The Ladykillers,” starring Alec Guinness and Peter Sellers. In the film, a gang of criminals poses as a string quintet, using recorded music as their cover while planning a heist. Their musical alibi? Boccherini’s Celebrated Minuet.

The irony is delicious: this most refined, aristocratic music becomes the soundtrack for deception. But the film also cemented the minuet’s association with sophistication and “fanciness” in popular culture. To this day, when a film or TV show needs shorthand for elegance or high society, Boccherini’s minuet often makes an appearance.

Recommended Recordings

For an authentic period-instrument experience, seek out recordings by ensembles like the Boccherini Quintet or Europa Galante. These groups use gut strings and baroque bows, producing the warmer, more intimate sound Boccherini would have known.

For a modern-instrument approach with beautiful clarity, the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center has performed this work with excellent results. Their interpretation balances historical awareness with contemporary polish.

If you’re just starting with Boccherini, the complete String Quintet in E major is worth your time—all four movements together run about 22-25 minutes. The opening Amoroso movement is particularly lovely, featuring muted strings throughout.

Why This Music Still Matters

There’s something almost countercultural about Boccherini’s minuet in our age of constant stimulation. It doesn’t demand attention with dramatic crescendos or startling dissonances. It simply offers four minutes of carefully crafted beauty, asking only that you slow down enough to receive it.

Perhaps that’s why it took a century to become “celebrated.” Perhaps we needed to lose something before we could appreciate what Boccherini was offering: music as a space for quiet feeling, for sensibilité, for the subtle pleasure of watching an elegant dance you’re not required to join.

Put it on during a quiet morning. Let the pizzicato notes settle around you like light through curtained windows. You’ll understand why Europe fell in love with this music—even if it took them a hundred years to realize it.