📑 Table of Contents

Picture this: Christmas Eve, 1830s Paris. A crowded café buzzes with bohemian artists, street vendors, and lovers. Into this chaos walks a stunning woman on the arm of a wealthy older man—but her eyes are locked on someone else entirely. Her ex-boyfriend sits at a nearby table, pretending not to notice her.

What does she do? She sings.

Not to her date. Not to the crowd. She sings at her former lover, weaponizing her own beauty in what might be opera’s most sophisticated act of psychological warfare.

This is “Quando me’n vo'” (When I Walk Alone), better known as Musetta’s Waltz from Puccini’s La Bohème. On the surface, it sounds like a charming, flirtatious tune. Underneath, it’s three minutes of calculated seduction that builds from innocent self-praise to outright emotional torture.

The Story Behind the Music

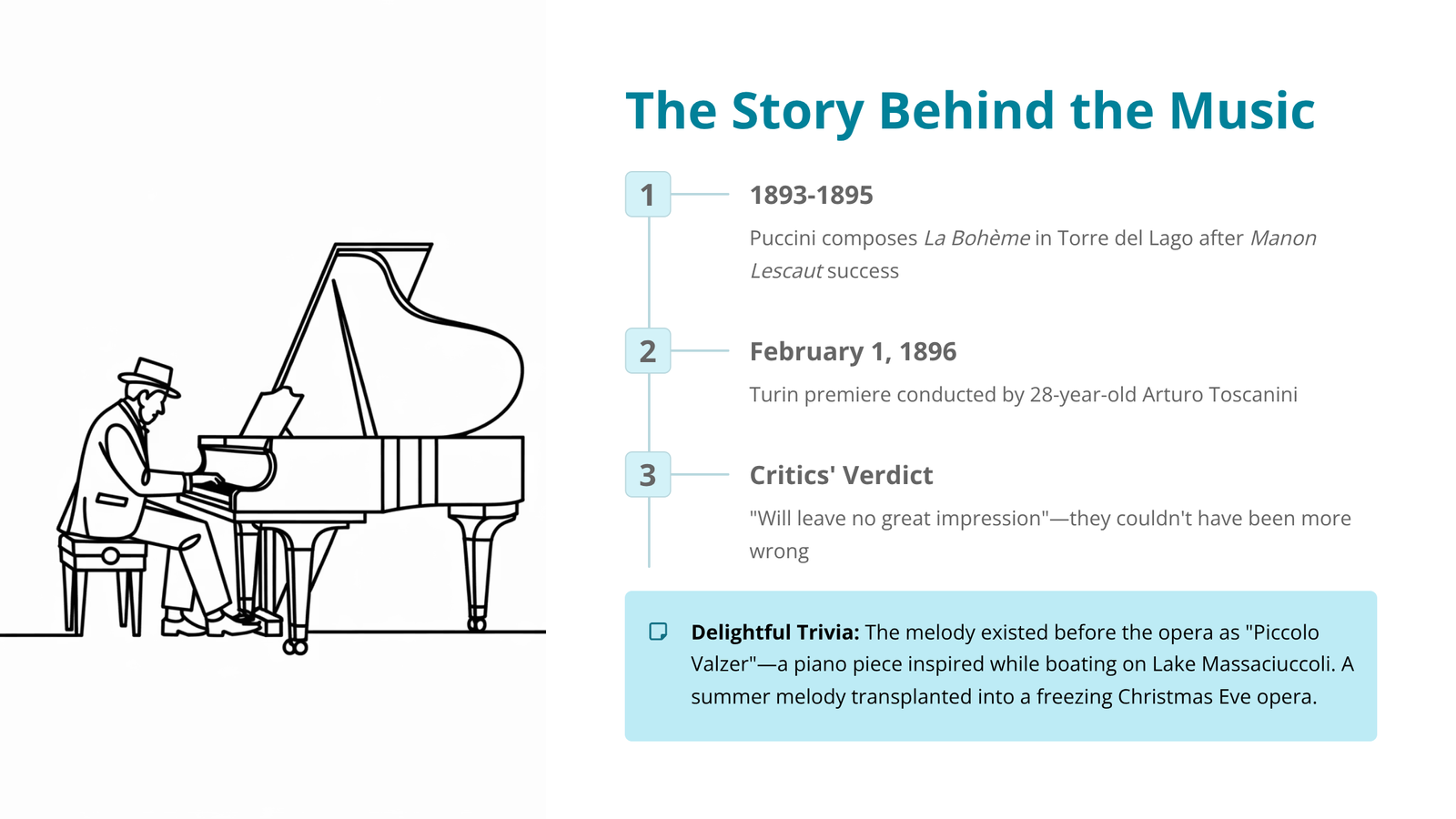

Giacomo Puccini composed La Bohème between 1893 and 1895, during a period when his life was finally stabilizing. His previous opera Manon Lescaut had been a hit, allowing him to settle in Torre del Lago, a small fishing village in Tuscany that became his creative sanctuary.

The opera premiered on February 1, 1896, in Turin, conducted by a 28-year-old Arturo Toscanini—who would later become one of the most legendary conductors in history. Critics were lukewarm at first. One reviewer even declared the work would leave “no great impression” on operatic history. They couldn’t have been more wrong.

Here’s a delightful piece of trivia: the melody for Musetta’s Waltz actually existed before the opera. Puccini originally composed it as a standalone piano piece called “Piccolo Valzer” (Little Waltz), reportedly inspired while boating on Lake Massaciuccoli near his home. A summer melody born from carefree moments on the water—later transplanted into a winter opera set on a freezing Christmas Eve. The contrast is intentional and brilliant.

Understanding Musetta: More Than Just a Flirt

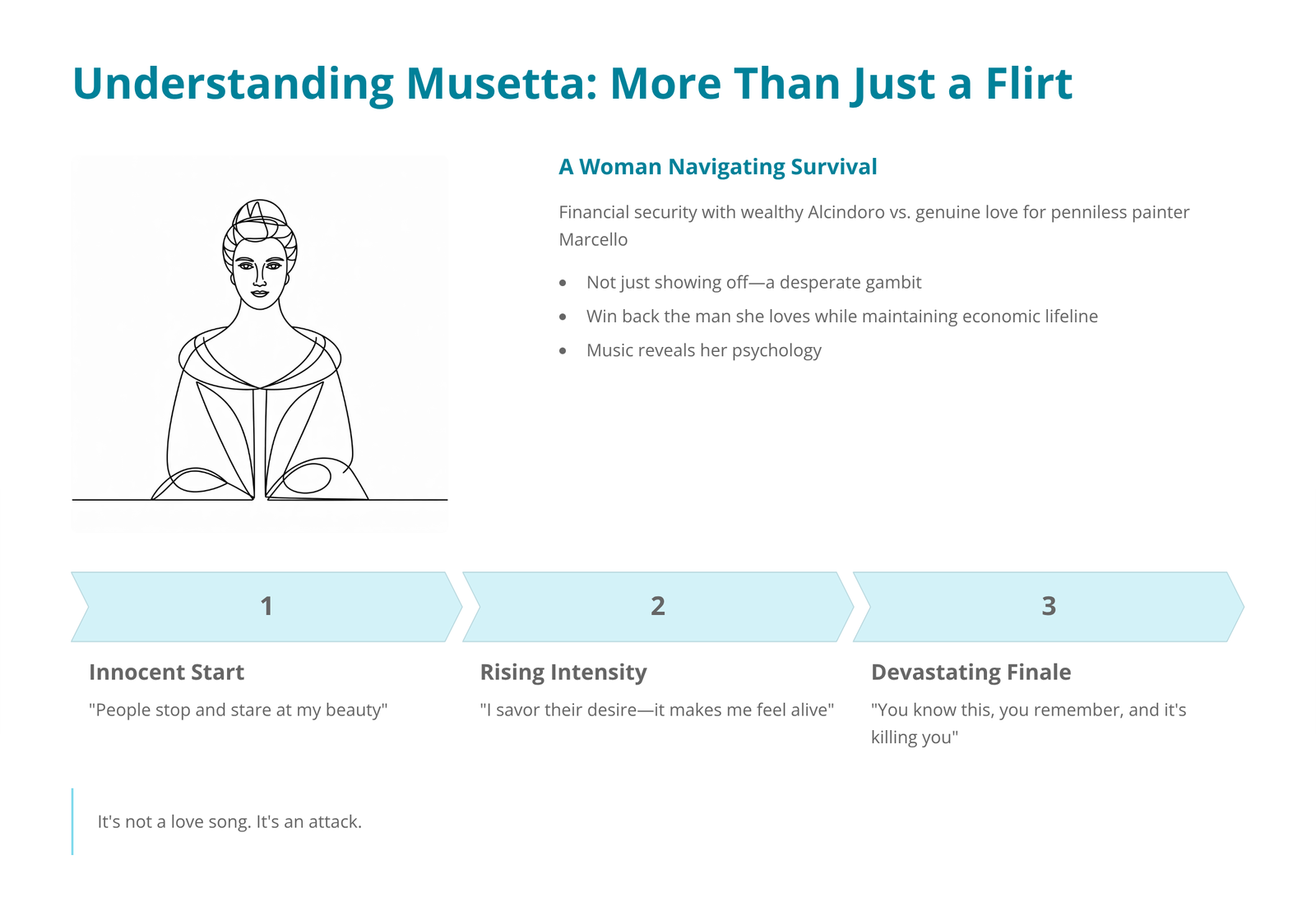

Musetta is often misunderstood as simply the “sexy one” compared to the fragile, doomed Mimì. But she’s far more complex than that.

She’s a woman navigating survival in 1830s Paris. She’s chosen financial security with the wealthy (and somewhat ridiculous) Alcindoro, but she can’t suppress her genuine feelings for the penniless painter Marcello. This aria isn’t just showing off—it’s a desperate gambit to win back the man she actually loves while maintaining her economic lifeline.

The genius of Puccini’s writing is how the music reveals her psychology. She starts with seemingly harmless observations: “When I walk alone through the streets, people stop and stare at my beauty.” Innocent enough. But as the aria progresses, she admits she savors their desire, that it makes her feel alive. And then comes the devastating final section where she directly addresses Marcello: “You know this, you remember, and it’s killing you inside.”

It’s not a love song. It’s an attack.

A Listening Guide: What to Notice

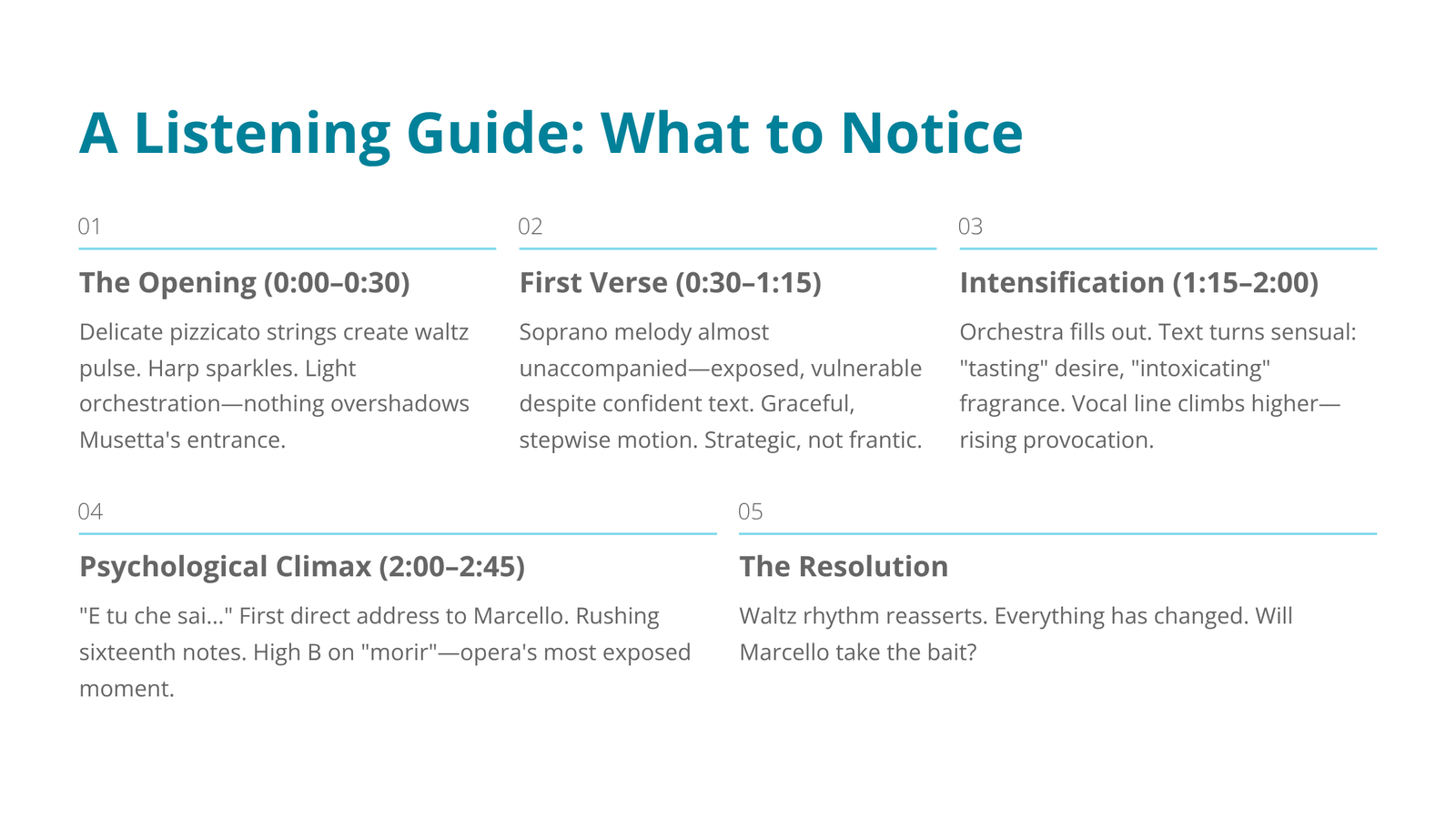

The Opening (0:00–0:30)

Listen for the delicate pizzicato strings (plucked rather than bowed) creating that characteristic waltz pulse. The harp adds sparkles of color. Puccini keeps the orchestration intentionally light here—nothing should overshadow Musetta’s entrance.

The First Verse (0:30–1:15)

The soprano melody begins almost unaccompanied, exposed and vulnerable despite the confident text. This is technically demanding—the singer must produce a pure, beautiful tone with almost no orchestral support. Notice how the melody moves in graceful, stepwise motion, avoiding dramatic leaps. Musetta is being strategic, not frantic.

The Intensification (1:15–2:00)

The orchestra gradually fills out as Musetta becomes bolder. The text turns more sensual: she speaks of “tasting” desire, of “intoxicating” fragrance. The vocal line climbs higher, mirroring her rising confidence—and her rising provocation.

The Psychological Climax (2:00–2:45)

Here’s where the aria transforms. “E tu che sai…” (And you who know this…). For the first time, she directly addresses Marcello. The rushing sixteenth notes in her vocal line convey barely contained triumph. The high B on “morir” (to die) is one of opera’s most exposed moments—sopranos must navigate a difficult diminuendo from loud to soft while maintaining perfect pitch and control.

The Resolution

The waltz rhythm reasserts itself, but everything has changed. Musetta has made her play. The question now is whether Marcello will take the bait.

Recommended Recordings

For the Classic Interpretation:

Renata Tebaldi’s 1959 recording captures what Toscanini called “la voce d’angelo” (the voice of an angel). Her rich, warm tone and impeccable legato make this the benchmark for many opera lovers. This is the version famously used in the 1987 film Moonstruck.

For Modern Brilliance:

Anna Netrebko brings a fresher, more playful approach that emphasizes Musetta’s mischievous charm. Her 2003 performance showcases remarkable agility and crystal-clear high notes.

For Historical Perspective:

Seek out the 1946 NBC broadcast conducted by Toscanini himself—the same man who led the world premiere fifty years earlier. It’s faster than modern performances, revealing what Puccini’s original tempo markings actually intended. The entire opera clocks in at just over 90 minutes, significantly quicker than today’s standard interpretations.

The Unlikely Pop Afterlife

Here’s something that might surprise you: this 19th-century aria became a 1950s pop hit. Twice.

In 1952, Sammy Kaye released a version called “You” that charted on the Billboard Top 40. But the bigger success came in 1959 when Della Reese recorded “Don’t You Know?” with new English lyrics. It reached number two on the Pop chart (only kept from the top spot by Bobby Darin’s “Mack the Knife”) and hit number one on the R&B chart, selling over a million copies and earning a Grammy nomination.

Classical music crossing over into popular culture isn’t new—but Musetta’s Waltz did it with particular grace, its irresistible melody proving that great tunes transcend genre boundaries.

Why This Aria Still Resonates

At its heart, “Quando me’n vo'” is about the complicated intersection of desire, pride, and vulnerability. Musetta uses her beauty as both shield and weapon, projecting supreme confidence while desperately seeking connection. She performs for an audience while speaking to only one person.

We’ve all known someone like Musetta. Maybe we’ve been someone like Musetta—putting on a show of indifference for the person we most want to notice us.

Puccini understood that beneath the flirtation and the waltz rhythm lies something universally human: the fear that the person we love might not love us back, and the sometimes absurd lengths we’ll go to find out.

The next time you hear this melody—whether in an opera house, a romantic comedy, or an elevator—listen past the pretty tune. There’s a whole psychological drama unfolding in three minutes, a woman gambling everything on a song.

And honestly? That kind of confidence is pretty irresistible.