📑 Table of Contents

Picture this: a London restaurant in the early 1970s, somewhere off the Fulham Road. Two men are finishing their meal when one of them walks over to the piano bar downstairs. He plays just eight or sixteen bars of a melody—something he had written for a forgettable thriller called The Walking Stick. The other man, legendary classical guitarist John Williams, immediately says: “Stanley, that is fantastic. You must expand that into a proper, full instrumental piece.”

That casual dinner conversation would eventually lead to one of the most recognizable and emotionally devastating guitar pieces of the twentieth century. Stanley Myers’ “Cavatina” would wait nearly a decade before finding its true purpose—as the soul of Michael Cimino’s 1978 masterpiece The Deer Hunter.

The Quiet Genius Behind the Melody

Stanley Myers was born in Birmingham, England in 1930. He attended King Edward’s School in Edgbaston and went on to score over sixty films and television productions throughout his career. His work ranged from horror films to BBC’s Question Time theme, and he even collaborated with a young Hans Zimmer in the 1980s.

But Myers was never a household name. He worked in the shadows of cinema, crafting soundscapes that served stories rather than demanding attention. His gift was restraint—the ability to say everything with almost nothing. This quality would define “Cavatina” and transform it from a simple film cue into something eternal.

The piece originally appeared in The Walking Stick (1970), a thriller directed by Eric Till that few remember today. Myers had composed it for piano, but when John Williams heard those opening bars in that London restaurant, he recognized something special hiding within the modest melody.

From Piano to Guitar: A Transformation

At Williams’ suggestion, Myers rewrote and expanded “Cavatina” for classical guitar. This wasn’t merely a transcription—it was a rebirth. The nylon strings of the classical guitar gave the melody a warmth and intimacy that the piano couldn’t quite capture. Williams first recorded this expanded version at Olympic Sound Studios in London, eventually releasing it on his 1971 album Changes.

Here’s a beautiful secret hidden in the opening notes: the first bars of “Cavatina” echo Mozart’s “Laudate Dominum” from his Solemn Vespers for a Confessor (K. 339). Myers transposed Mozart’s accompaniment pattern from F major to E major, creating a subtle connection to sacred music that most listeners feel without ever knowing why. This borrowed reverence gives “Cavatina” its prayer-like quality from the very first note.

The word “cavatina” itself comes from Italian, meaning a short, simple song—often found in operas. Myers’ composition lives up to this definition perfectly: a lyrical, arpeggiated melody in slow tempo, emphasizing emotional restraint through fingerstyle technique on nylon strings.

The Deer Hunter: Where Tragedy Met Its Voice

For seven years, “Cavatina” existed in relative obscurity. Classical guitar enthusiasts knew it from Williams’ recordings. Cleo Laine had added lyrics in 1973, recording it as “He Was Beautiful” with Williams accompanying her. But the piece hadn’t yet found its larger purpose.

Then came The Deer Hunter.

Director Michael Cimino was crafting his epic about three Pennsylvania steelworkers—Michael (Robert De Niro), Nick (Christopher Walken), and Steven (John Savage)—whose lives are shattered by the Vietnam War. Cimino’s production assistant gave him a copy of Williams’ Changes album. When Cimino heard “Cavatina,” he knew he had found his film’s emotional anchor.

The film uses the piece non-diegetically, meaning the characters can’t hear it—only we can. It appears during pivotal transitions between scenes of domestic warmth and the horrors of war, between the small-town wedding celebrations and the psychological devastation that follows. The melody doesn’t comment on what we see; it mourns it in advance.

Listening Guide: Finding the Heartbreak

“Cavatina” runs approximately three to four minutes in most recordings, but every second carries weight. Here’s how to truly experience it:

Opening (0:00–0:30): The piece begins with those Mozart-inspired arpeggios in E major. Notice how Williams lets each note ring and decay naturally. There’s no hurry. The guitar breathes. Listen for the way the melody emerges from the accompaniment like a voice rising from prayer.

First Theme Development (0:30–1:30): The main melody unfolds with remarkable simplicity. Myers uses what musicians call “one note per bar” in certain passages—a technique that creates maximum emotional impact with minimum notes. Pay attention to the sustain, how Williams maintains a singing tone throughout.

Middle Section (1:30–2:30): The harmonies become slightly more complex here, with subtle shifts that create a sense of gentle questioning. The melody seems to search for something, never quite finding resolution. This is where many listeners feel the first sting of tears.

Return and Resolution (2:30–end): The opening theme returns, but now we hear it differently. Everything we’ve experienced in the middle section colors our perception. The final notes fade into silence, leaving us with a profound sense of beautiful incompleteness.

Pro tip: Listen with headphones in a quiet room. This piece rewards intimate attention. The spaces between notes matter as much as the notes themselves.

Recommended Recordings

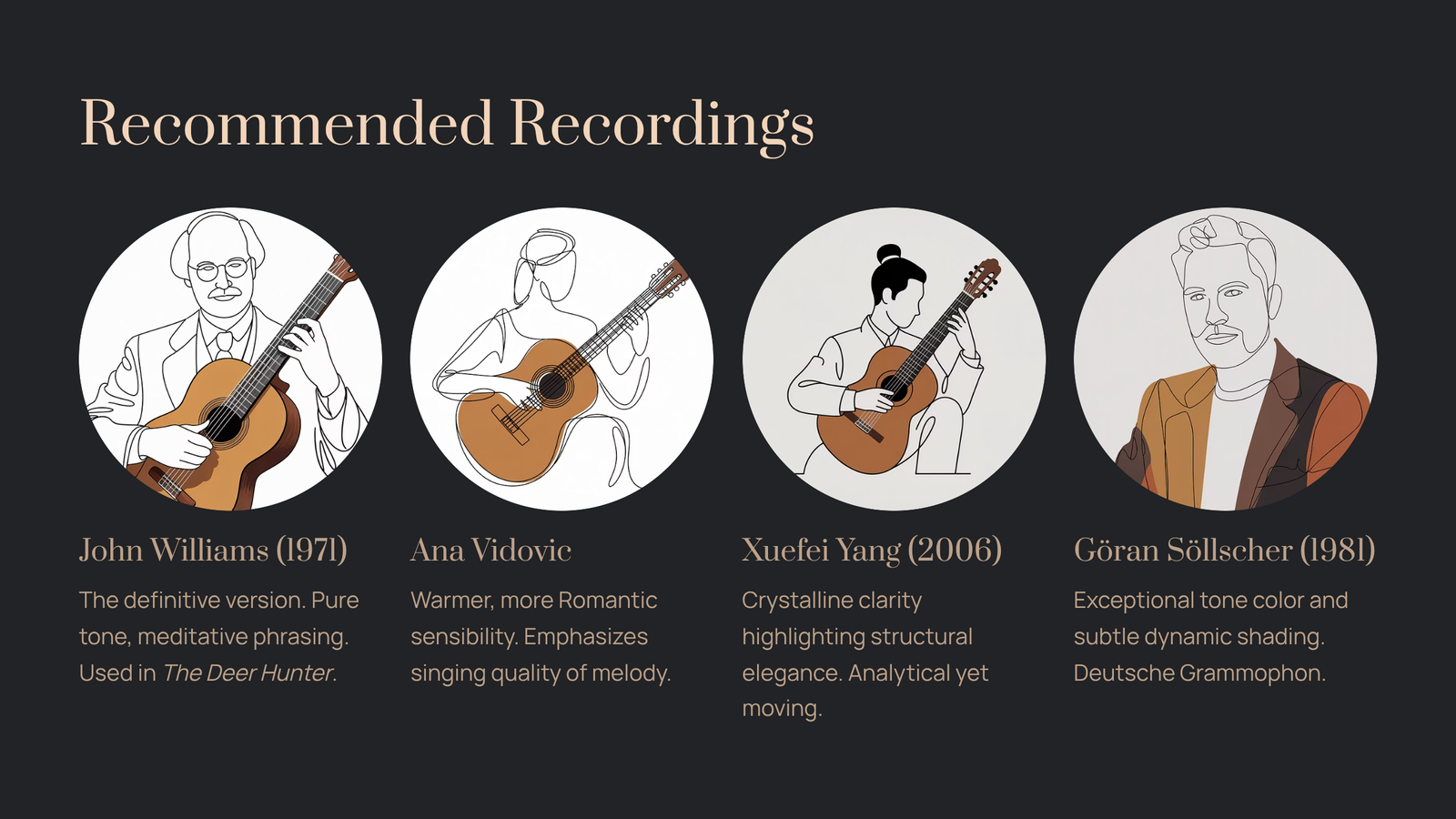

John Williams (1971, Changes) — The definitive version. Williams’ interpretation set the standard that all others follow. His tone is pure, his phrasing is meditative, and his technical control allows the emotion to speak without interference. This is the recording used in The Deer Hunter.

Ana Vidovic — The Croatian guitarist brings a slightly warmer, more Romantic sensibility to the piece. Her interpretation emphasizes the singing quality of the melody even more than Williams’, though some purists prefer the original’s restraint.

Xuefei Yang (2006, Romance de Amor) — Yang’s recording offers a crystalline clarity that highlights the piece’s structural elegance. Her approach is somewhat more analytical but no less moving.

Göran Söllscher (1981, Deutsche Grammophon) — The Swedish guitarist’s version is notable for its exceptional tone color and subtle dynamic shading.

Why This Piece Still Devastates Us

Music critics have praised “Cavatina” for its melodic sweetness and structural clarity. Benjamin Verdery, the renowned guitarist, has highlighted its emotional depth and accessibility. But some have called it “middle-brow” or “commercially oriented” compared to the complex cavatinas of Beethoven’s late string quartets.

They miss the point entirely.

“Cavatina” doesn’t devastate us because of harmonic complexity or contrapuntal brilliance. It devastates us because it captures something universal: the ache of irreversible loss, the beauty that exists precisely because it cannot last. When the melody plays over scenes of young men about to leave for war, over friendships that will be destroyed, over a community that doesn’t yet know what’s coming—we feel the weight of all the goodbyes we’ve ever said.

The piece works through absence as much as presence. Myers understood that grief lives in the spaces between notes, in the silences that separate one phrase from the next. He wrote a melody that sounds like memory itself—vivid but unreachable, present but already fading.

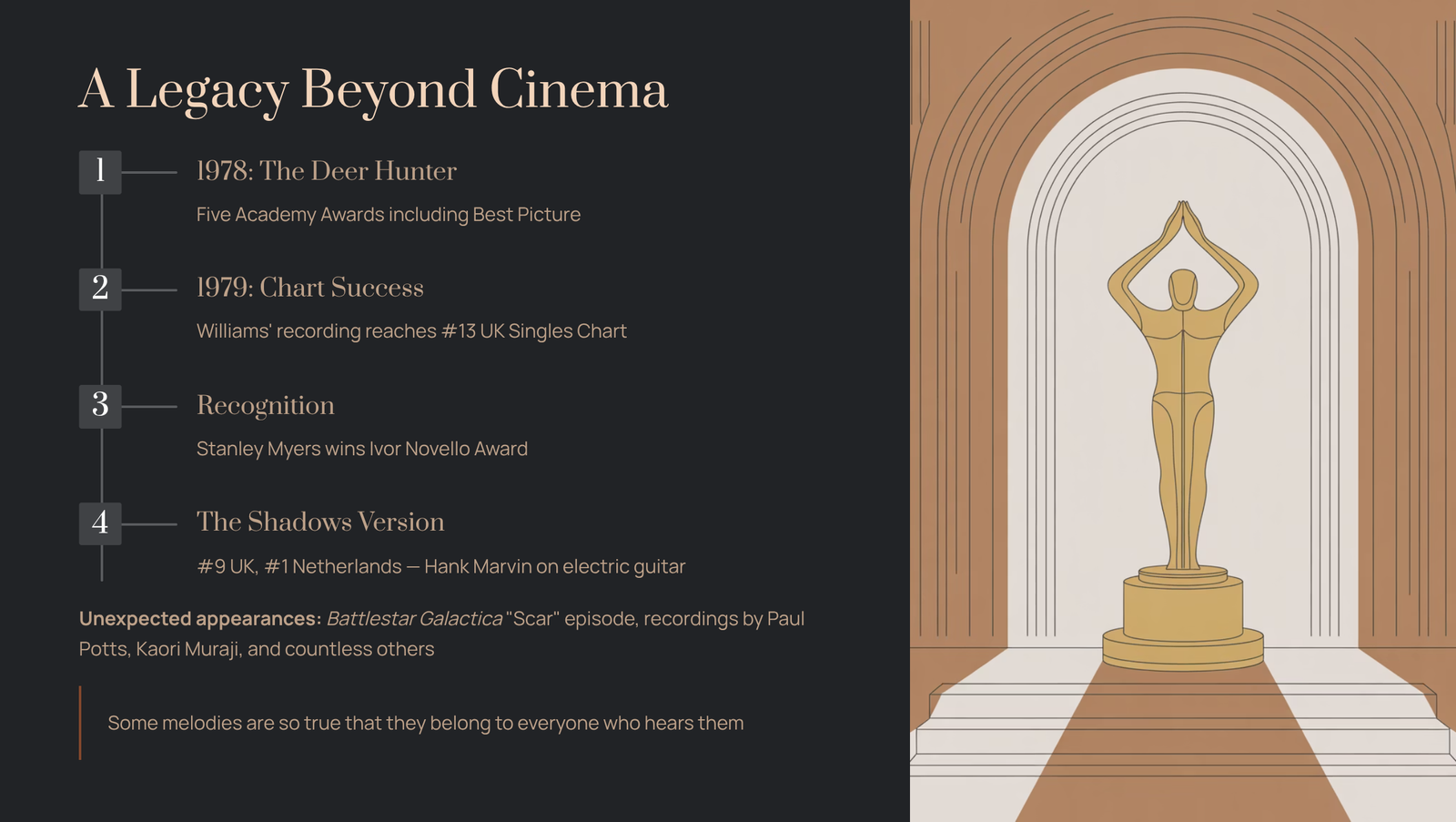

A Legacy Beyond Cinema

After The Deer Hunter won five Academy Awards, including Best Picture, “Cavatina” entered popular consciousness in a way few classical guitar pieces ever have. Williams’ recording reached number 13 on the UK Singles Chart in 1979. The Shadows recorded a version featuring Hank Marvin on electric guitar that hit number 9 in the UK and topped the charts in the Netherlands.

Stanley Myers won the Ivor Novello Award for the composition—fitting recognition for a piece that had traveled such an unlikely path from a forgotten thriller to an Oscar-winning epic.

The melody continues to appear in unexpected places. It plays at the end of the Battlestar Galactica episode “Scar,” as Kara “Starbuck” Thrace toasts fallen pilots. It has been recorded by artists ranging from Paul Potts to Kaori Muraji. Each new interpretation proves what that dinner in London first revealed: some melodies are so true that they belong to everyone who hears them.

The One Shot Philosophy

The Deer Hunter contains a recurring motif about deer hunting and the importance of “one shot”—killing the deer cleanly with a single bullet. Michael (De Niro) believes in this philosophy with almost religious intensity. But by the film’s end, after everything he has witnessed, he can no longer pull the trigger at all.

“Cavatina” embodies this same principle in musical form. Myers achieved everything with one melody, one guitar, one emotional truth. No orchestral swells. No dramatic crescendos. Just a simple song that accomplishes more with its restraint than a hundred bombastic scores could manage.

Sometimes the most powerful thing you can do is hold back. Let the silence speak. Trust the listener to feel what you’ve left unsaid.

This is what Stanley Myers understood, what John Williams captured in his interpretation, and what The Deer Hunter burned into cinema history. “Cavatina” is proof that music doesn’t need to be complicated to be profound. It only needs to be honest.

And in its honesty, it offers us something rare: permission to feel the full weight of our own losses, our own memories, our own quiet devastation. Three minutes of guitar, and somehow we’re mourning everything we’ve ever loved and lost.

That’s why the melody still haunts us, nearly fifty years later. That’s why it always will.