📑 Table of Contents

- A Train Conversation That Changed Musical History

- What Does Jupiter “Sound” Like?

- The Melody Everyone Knows (But Can’t Name)

- A Listening Guide for First-Time Explorers

- The Premiere No One Expected to Work

- Why Holst Regretted His Greatest Hit

- Recommended Recordings to Start Your Journey

- Why Jupiter Still Matters

Picture this: London, September 1918. The final weeks of World War I. A hastily arranged concert in Queen’s Hall, where musicians are sight-reading music they received just two hours before curtain. And somewhere in the audience, cleaning ladies abandon their duties to dance in the aisles.

This wasn’t chaos—it was the premiere of Gustav Holst’s Jupiter, the Bringer of Jollity, a piece so irresistibly joyful that even those who came to sweep the floors couldn’t help but move. Holst’s own daughter Imogen witnessed this remarkable scene and never forgot it.

What makes this eight-minute orchestral celebration so infectious? And why did Holst himself come to regret his greatest success? Let’s explore.

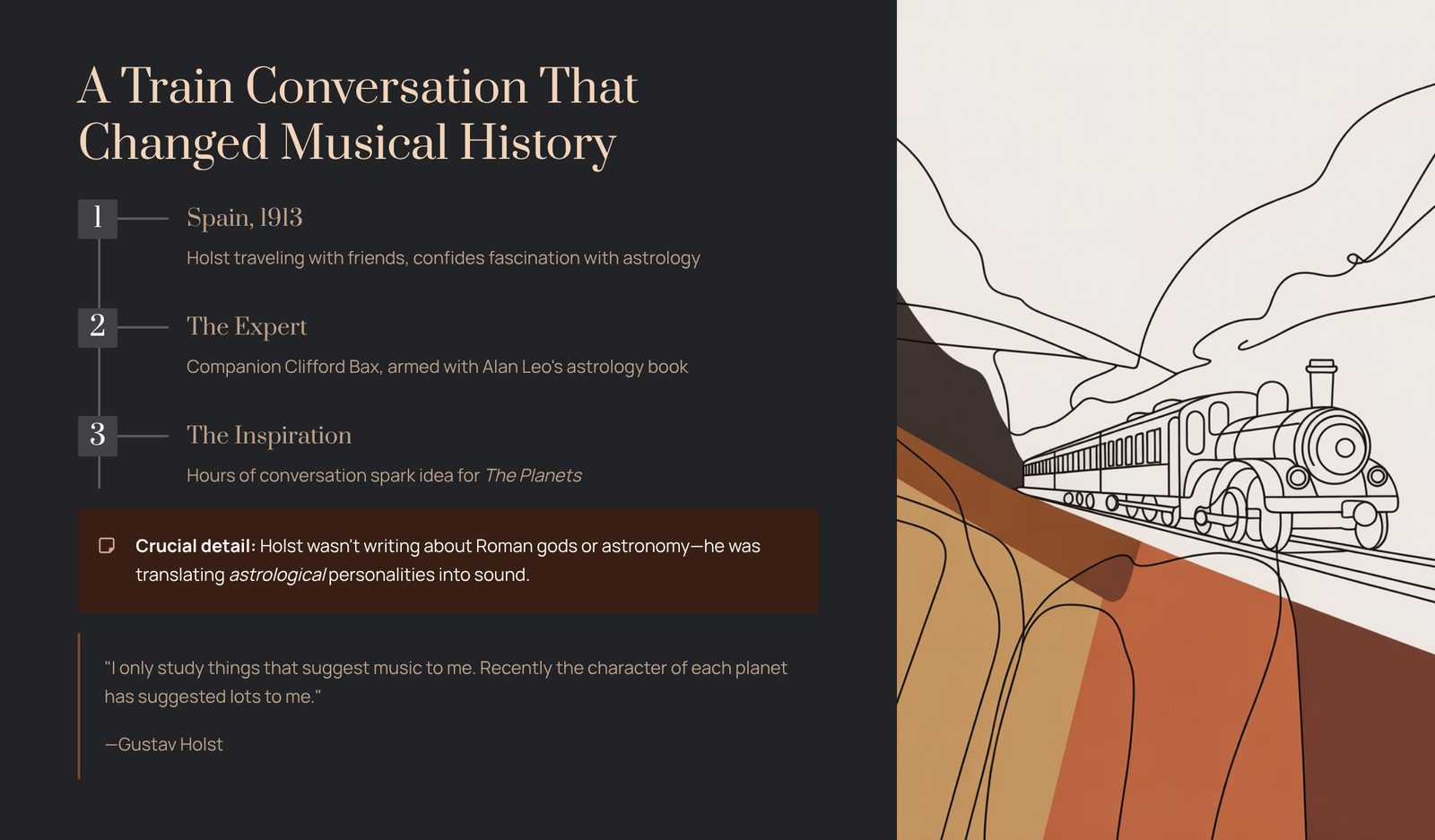

A Train Conversation That Changed Musical History

The story of Jupiter begins not in a concert hall, but on a train rattling through Spain in 1913. Gustav Holst, a 38-year-old English composer, was traveling with friends when he confided something unexpected: he’d become fascinated with astrology.

His companion Clifford Bax happened to be an expert on the subject. Armed with a book called What is a horoscope and how is it cast? by the famous astrologer Alan Leo, the two spent hours in deep conversation. By the time they reached their destination, Holst had found the inspiration for what would become his masterpiece: The Planets.

But here’s the crucial detail—Holst wasn’t writing about Roman gods or astronomical science. He was translating astrological personalities into sound. As he wrote to a friend: “I only study things that suggest music to me. Recently the character of each planet has suggested lots to me.”

What Does Jupiter “Sound” Like?

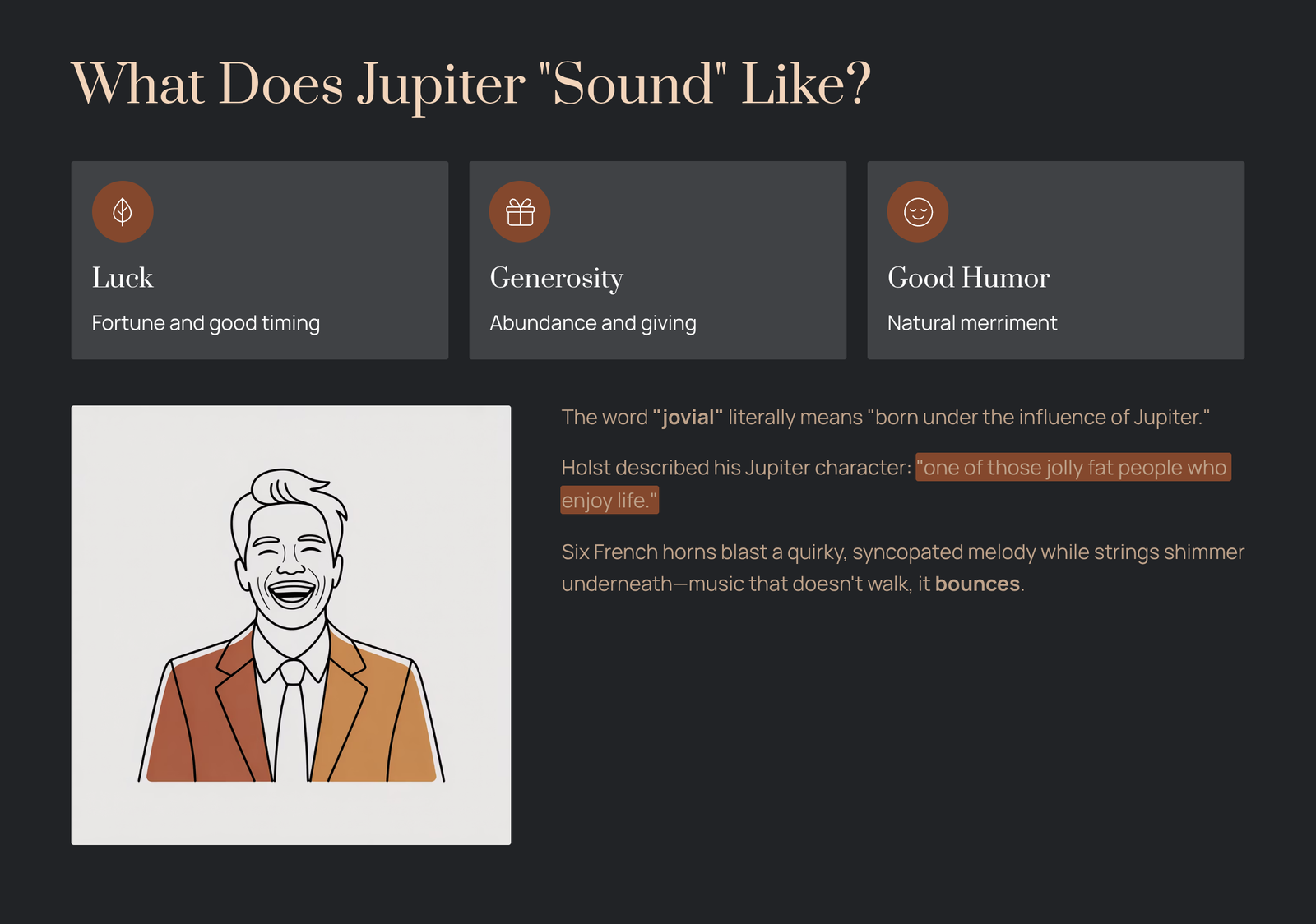

In astrological tradition, Jupiter represents luck, generosity, abundance, and good humor. The word “jovial” literally means “born under the influence of Jupiter”—ancient astrologers believed people influenced by this planet were naturally merry and good-natured.

Holst described his Jupiter character with delightful directness: “one of those jolly fat people who enjoy life.”

Listen to the opening and you’ll hear exactly that. Six French horns blast out a quirky, syncopated melody while strings shimmer underneath in a pattern that seems to tumble over itself with enthusiasm. It’s music that doesn’t walk—it bounces.

The Melody Everyone Knows (But Can’t Name)

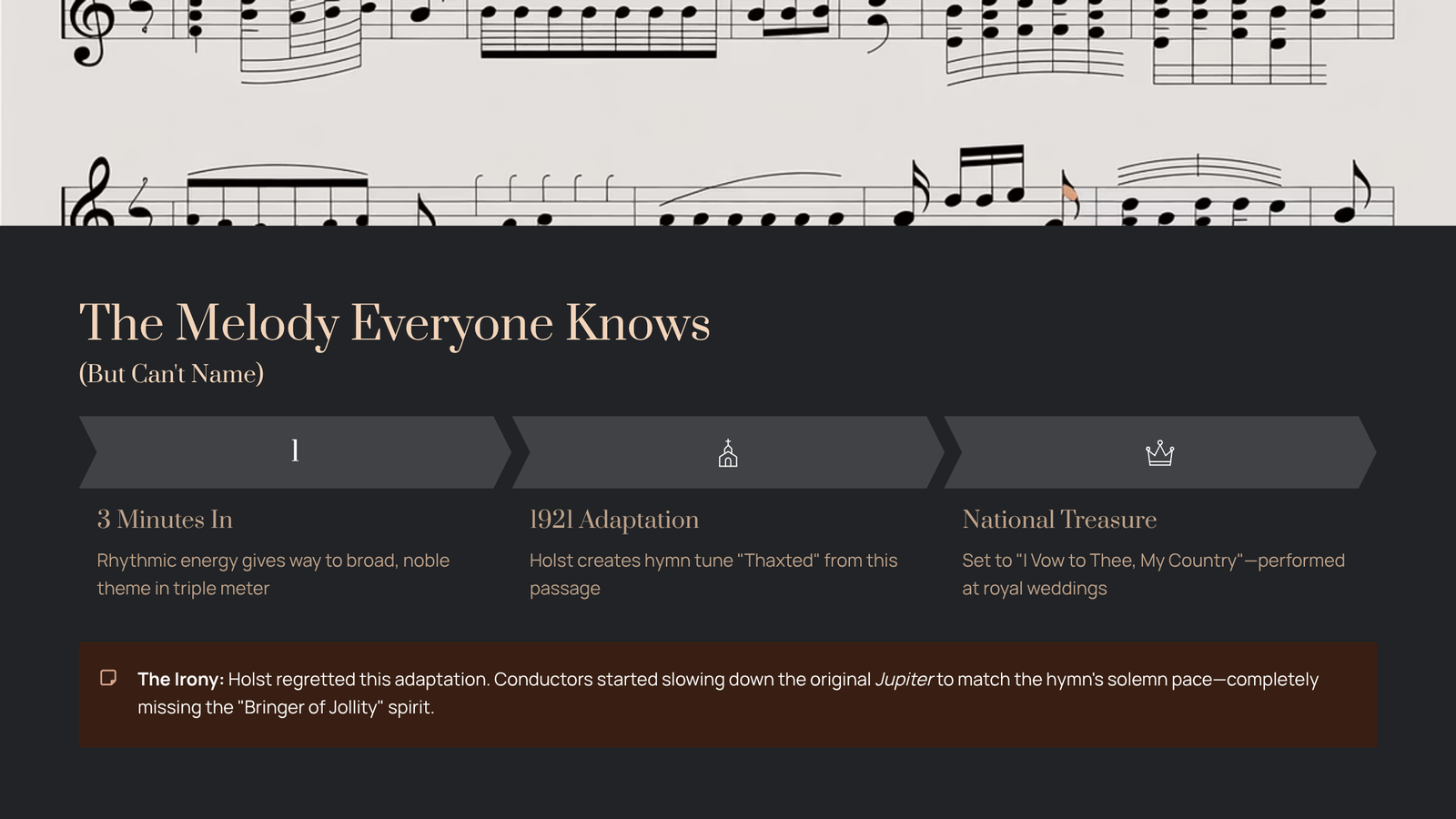

About three minutes in, something magical happens. The rhythmic energy suddenly gives way to a broad, noble theme in triple meter—a melody so beautiful it feels like it’s always existed.

If it sounds familiar, there’s a reason. In 1921, Holst adapted this passage into a hymn tune called “Thaxted” (named after the Essex village where he composed The Planets). Set to the patriotic poem “I Vow to Thee, My Country,” it became one of Britain’s most beloved hymns, regularly performed at royal weddings and national ceremonies.

Here’s the irony: Holst came to regret this adaptation. Why? Because conductors started slowing down the original Jupiter to match the hymn’s solemn pace—completely missing the “Bringer of Jollity” spirit he intended.

A Listening Guide for First-Time Explorers

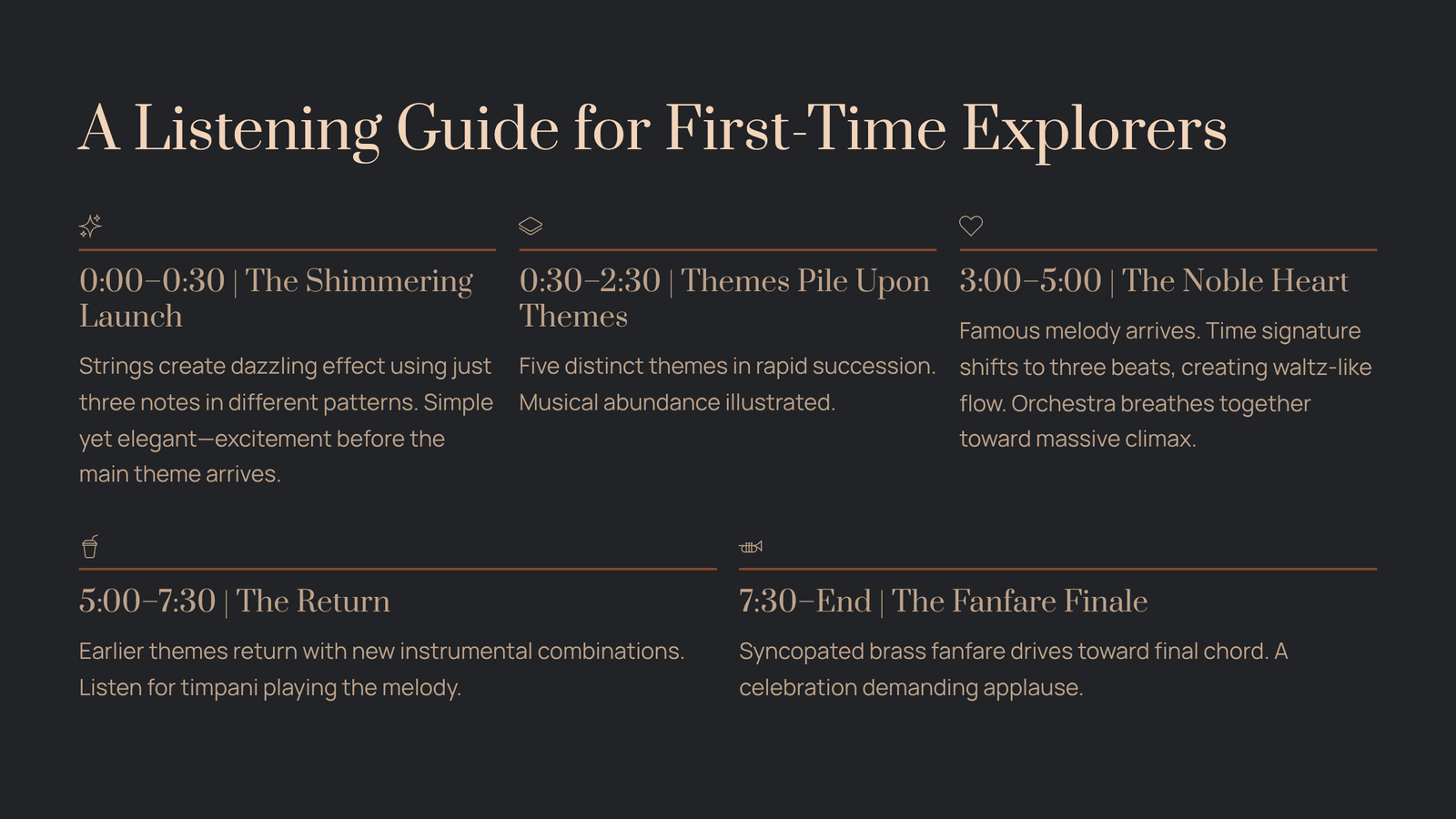

0:00–0:30 | The Shimmering Launch

Pay attention to the strings at the very beginning. Holst creates a dazzling effect using just three notes repeated in different patterns across two octaves. It sounds complex, but it’s elegantly simple—and it creates that sense of excitement before the main theme even arrives.

0:30–2:30 | Themes Pile Upon Themes

Unlike many classical pieces that develop one or two ideas, Jupiter throws five distinct themes at you in rapid succession. Just when you think you’ve grasped one, another appears. This isn’t randomness—it’s abundance, musically illustrated.

3:00–5:00 | The Noble Heart

Here comes that famous melody. Notice how Holst changes the time signature from four beats to three, creating a waltz-like flow. The entire orchestra seems to breathe together as this theme builds to a massive climax.

5:00–7:30 | The Return

Earlier themes come back, but Holst keeps things fresh with new instrumental combinations. Listen for the timpani—unusually, Holst wrote the melody so it could be played entirely on these drums.

7:30–End | The Fanfare Finale

A syncopated brass fanfare drives toward the final chord. The ending isn’t subtle—it’s a celebration demanding applause.

The Premiere No One Expected to Work

The circumstances of the 1918 premiere were almost comically unprepared. With World War I still raging, conductor Adrian Boult had minimal rehearsal time. The musicians barely knew the music. The whole event was privately funded by fellow composer Balfour Gardiner and attended by just 250 invited guests.

Against all odds, it was a triumph. The Sunday Times critic Ernest Newman declared Holst “one of the subtlest and original minds of our time,” comparing him to Stravinsky and Strauss. The cleaning ladies danced. And when the final movement Neptune faded into silence, Holst’s daughter described it as “unforgettable… until the imagination knew no difference between sound and silence.”

Why Holst Regretted His Greatest Hit

Here’s perhaps the strangest part of this story: the massive success of The Planets made Holst miserable.

He believed his other works were better. He felt trapped by the public’s demand for this one piece. According to some accounts, he completely lost motivation to compose after The Planets became famous, feeling it cast a shadow over everything else he created until his death in 1934.

It’s a reminder that artistic success and artistic satisfaction don’t always align—and that even the most joyful music can come with complicated feelings.

Recommended Recordings to Start Your Journey

For Audiophile-Quality Sound: James Levine with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra delivers perhaps the most intense experience, with outstanding percussion and excellent balance between strings and brass.

For Old-School Grandeur: Herbert von Karajan’s recording offers a glossy, beautiful sound with unusual prominence given to the violas—a distinctive interpretive choice.

For Something Different: André Previn with the London Symphony Orchestra has been a longtime favorite, while Charles Dutoit’s Montreal recording is frequently cited as one of the finest available.

For Historical Context: Seek out recordings by Adrian Boult, who conducted that legendary 1918 premiere and continued championing this music for decades.

Why Jupiter Still Matters

More than a century after those cleaning ladies danced at Queen’s Hall, Jupiter remains one of the most performed orchestral works by any British composer. It’s been used in everything from Hunter x Hunter anime episodes to the children’s show Bluey, where viewers have reported being moved to tears.

What makes it endure? Perhaps it’s that Holst captured something universally human—the feeling of unbridled joy, the experience of abundance, the sensation of life being genuinely, thoroughly good. Not escapism, but celebration.

The next time you need a reminder that life can be magnificent, put on Jupiter. And if you find yourself dancing in the aisles, you’ll be in excellent company.