📑 Table of Contents

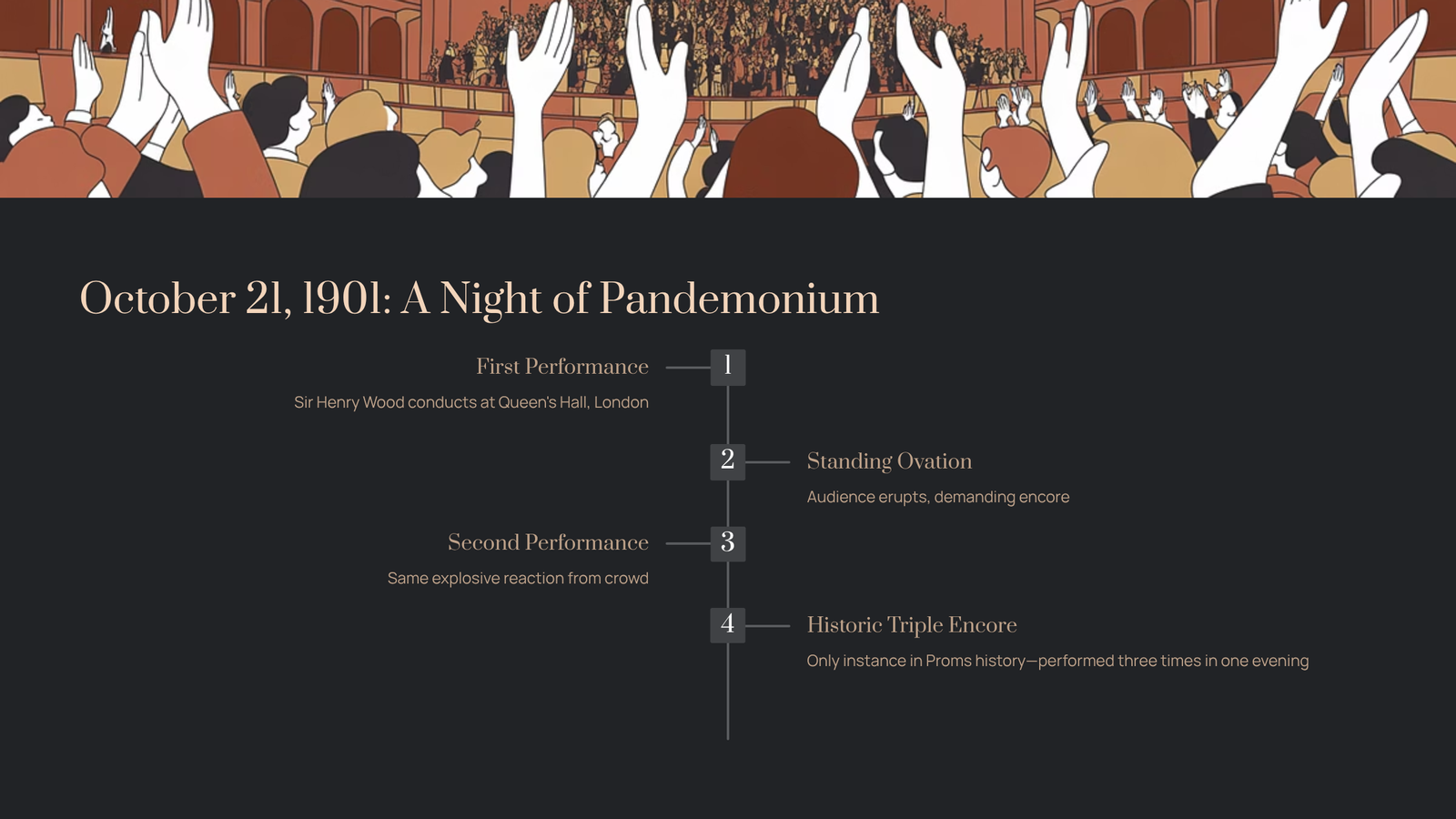

On the evening of October 21, 1901, something extraordinary happened at London’s Queen’s Hall. Conductor Sir Henry Wood had just finished performing a new orchestral march by a relatively unknown English composer. What followed was pandemonium.

The audience didn’t just applaud. They rose to their feet and shouted. Wood had no choice but to play it again. Same result. The crowd refused to let the concert continue. In what remains the only instance in the entire history of the Proms, an orchestral piece received a double encore—meaning it was performed three times in a single evening.

That piece was Edward Elgar’s Pomp and Circumstance March No. 1. And the melody that drove audiences into a frenzy that night? You’ve almost certainly heard it. Every year, millions of graduates around the world walk across stages to its triumphant strains.

But this isn’t just graduation background music. It’s a masterpiece with a story worth knowing.

A Composer Who Knew He Had Something Special

Edward Elgar was a self-taught musician from modest origins, which was unusual in the elite world of classical composition. By 1901, he was living in Great Malvern with his wife Alice, still working to establish himself as a serious composer despite the success of his Enigma Variations two years earlier.

When Elgar composed the Pomp and Circumstance March No. 1 in the summer of 1901, he wrote it remarkably quickly—sketches began in early June, and the full orchestration was complete by July. He knew he had created something powerful. In a letter to a friend, he wrote with characteristic confidence: “I’ve got a tune that will knock ’em flat.”

He wasn’t wrong.

The title comes from Shakespeare’s Othello: “Pride, pomp, and circumstance of glorious war!” It was a fitting choice for a work that channeled the imperial confidence of Edwardian Britain at the height of its power.

Two Souls in One March

What makes this march so effective is its dual personality. It’s really two contrasting pieces woven into one.

The opening is pure military energy. Picture a parade ground at dawn—trumpets blaring, drums thundering, the whole orchestra surging forward with unstoppable momentum. Elgar marks it Allegro, con molto fuoco (fast, with much fire), and the brass section delivers exactly that kind of blazing intensity.

Then everything changes.

The famous Trio section arrives like sunlight breaking through storm clouds. Where the march was forceful and driving, this melody is broad, noble, and deeply moving. The first violins introduce it softly, supported by warm French horns, while harps add gentle sparkle underneath. It’s the kind of tune that makes you want to stand up straighter.

When this melody returns later in the piece, Elgar adds a pipe organ, transforming it into something almost hymn-like in its grandeur. This wasn’t accidental—King Edward VII himself later suggested setting this melody to words, which became the patriotic song “Land of Hope and Glory.”

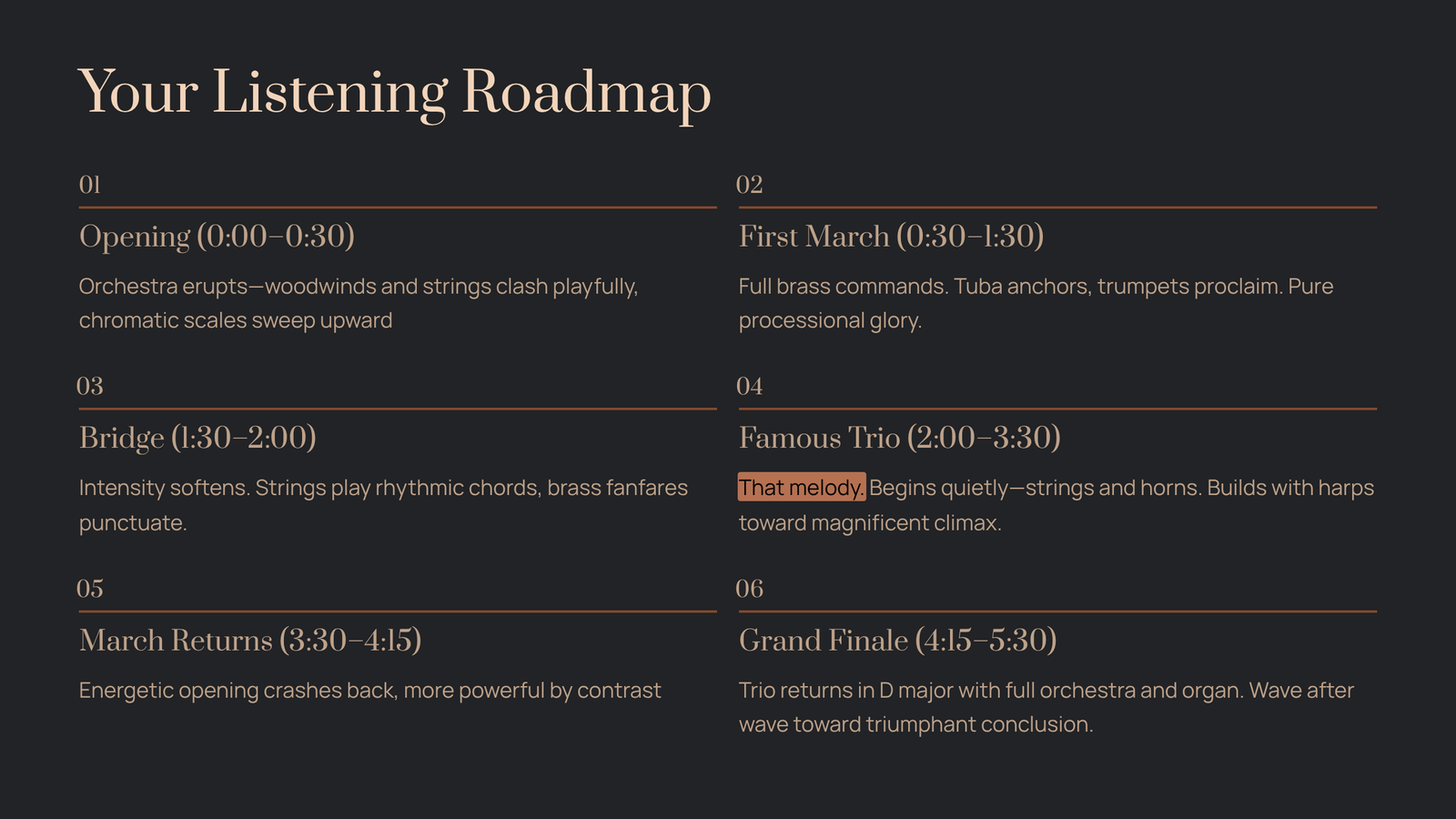

Your Listening Roadmap

Here’s how to follow the emotional journey of this six-minute masterpiece:

Opening (0:00–0:30) — The orchestra erupts with fiery energy. Listen for how the woodwinds and strings seem to clash playfully in the upper and lower registers before chromatic scales sweep everything upward.

First March Theme (0:30–1:30) — The full brass section takes command. Pay attention to the powerful tuba anchoring the bottom while trumpets proclaim the main theme. This is pure processional glory.

Bridge Passage (1:30–2:00) — The intensity gradually softens. Strings play rhythmic chords while brass fanfares punctuate the texture, preparing us for what’s coming.

The Famous Trio (2:00–3:30) — Here it is: that melody. Notice how quietly it begins—just strings and horns in a tender, almost intimate statement. Then it builds, with harps joining in and the dynamics swelling toward a magnificent climax.

March Returns (3:30–4:15) — The energetic opening material crashes back, but now it feels even more powerful by contrast with the lyrical Trio.

Grand Finale (4:15–5:30) — The Trio melody returns one last time, now in the home key of D major with full orchestra and organ. This is the climax of the entire work—wave after wave of orchestral sound cresting toward a triumphant conclusion.

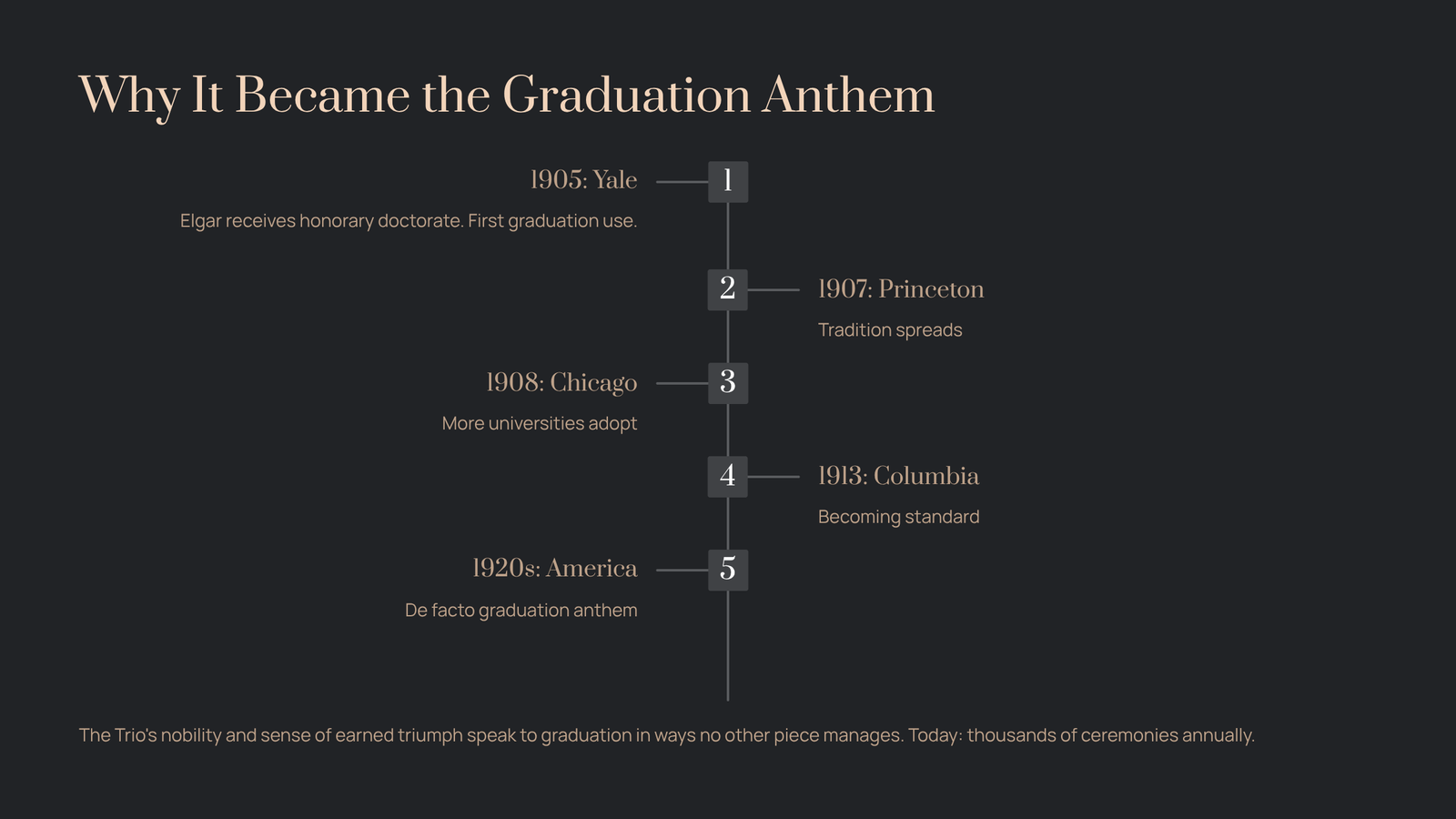

Why It Became the Graduation Anthem

The connection to graduation ceremonies was pure serendipity.

In June 1905, Elgar traveled to Yale University to receive an honorary doctorate. The university chose to play his march during the ceremony—the first time it had been used for a graduation. Princeton followed in 1907, then the University of Chicago in 1908, Columbia in 1913, and the tradition spread like wildfire.

By the 1920s, Pomp and Circumstance had become the de facto graduation anthem across America. Today, it’s performed at thousands of high school and university ceremonies every year. For many people, this melody is the sound of achievement, of chapters ending and new ones beginning.

There’s something fitting about this. The Trio’s nobility, its sense of earned triumph and hopeful forward motion—these qualities speak to the graduation experience in ways no other piece quite manages.

Recordings Worth Your Time

For historical authenticity: Seek out recordings by Sir Adrian Boult, who worked directly with Elgar and understood his intentions intimately. His interpretations are dignified, clean, and authoritative.

For pure orchestral spectacle: Leonard Bernstein’s performances with the New York Philharmonic bring extra drama and passion. His Trio sections have an almost operatic sweep.

For the authentic Proms experience: Look for recordings from the Last Night of the Proms, where the tradition lives on. The audience still rises to sing along with “Land of Hope and Glory”—a century-old tradition that continues to move crowds to their feet.

For newcomers: The BBC Symphony Orchestra recordings offer excellent sound quality and balanced interpretations that let you hear all the orchestral details clearly.

More Than Background Music

It’s easy to dismiss Pomp and Circumstance March No. 1 as mere ceremonial wallpaper—something you’ve heard so many times it has lost its meaning. But listen to it fresh, with full attention, and you’ll understand why that Queen’s Hall audience in 1901 demanded to hear it three times.

Elgar poured genuine craft into this work. The orchestration is brilliant, layering instruments with expert precision. The harmonic language, beneath its accessible surface, shows the influence of Wagner and the German Romantic tradition. And that Trio melody—simple as it seems—is perfectly constructed, each phrase building on the last toward inevitable emotional climax.

Sometimes the most popular works in classical music earned their popularity honestly. This is one of them.

The next time you hear it at a graduation, in a film, or during a royal ceremony, try to hear past the familiarity. Underneath is a piece of music that made a roomful of Edwardian Londoners lose their composure entirely—and still has the power to do the same today.