📑 Table of Contents

There’s a story—perhaps apocryphal, perhaps not—that Chopin once lifted his arms, clasped his hands together, and cried out: “O, my fatherland!”

He wasn’t on a stage. He wasn’t performing for royalty. He was simply listening to his student play through a piece he’d written a few years earlier. The melody had transported him somewhere else entirely—back to a homeland he would never see again.

That piece was his Étude in E major, Op. 10 No. 3. Today, we know it by a name Chopin never gave it: Tristesse—French for “sadness.”

The Exile Who Couldn’t Return

To understand this étude, you need to understand what Chopin left behind.

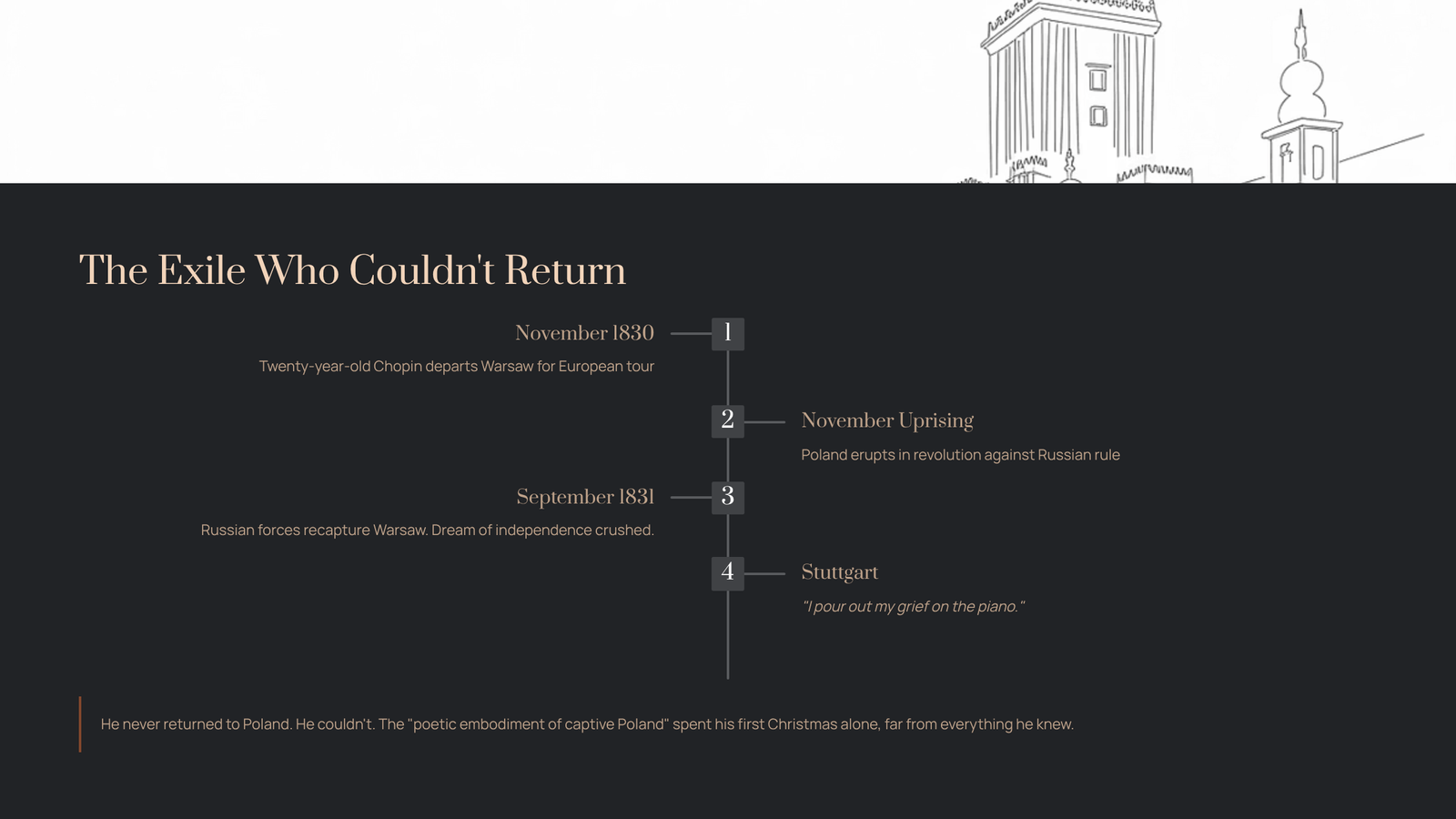

In November 1830, just weeks after the twenty-year-old composer departed Warsaw for a European concert tour, Poland erupted in revolution. The November Uprising against Russian rule would rage for nearly a year before collapsing in September 1831. Russian forces recaptured Warsaw. The dream of Polish independence was crushed.

Chopin learned of the catastrophe while traveling through Stuttgart. In his diary, he wrote words that would echo through his music for the rest of his life: “I pour out my grief on the piano.”

He never returned to Poland. He couldn’t. For the rest of his days, Chopin remained what the Parisian salons called him: the “poetic embodiment of captive Poland.” By the time he composed this étude in August 1832, he had spent his first Christmas alone, far from everything he knew.

A Melody He Called His Greatest

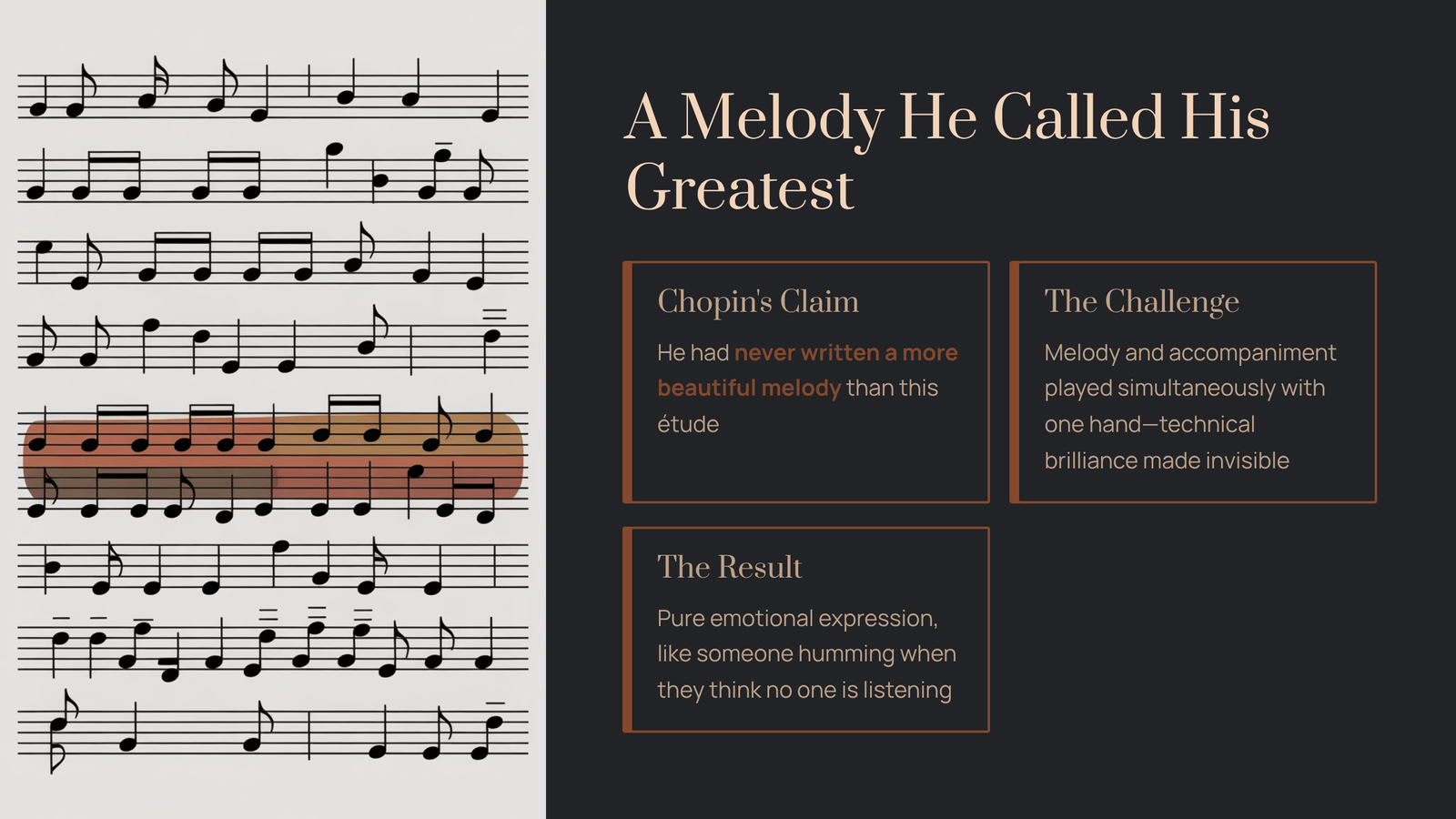

Here’s something remarkable: Chopin explicitly stated that he had never written a more beautiful melody than the one in this étude. Consider the weight of that claim. By 1832, he had already composed dozens of mazurkas, nocturnes, and preludes. Yet this simple, singing line—meant ostensibly as a technical exercise—represented something he couldn’t surpass.

What makes it so special?

The melody enters quietly, almost hesitantly, carried by the right hand while the same hand simultaneously provides its own gentle accompaniment. It’s an intimate sound, like someone humming to themselves when they think no one is listening. The technical challenge—playing melody and accompaniment with one hand—becomes invisible. What remains is pure emotional expression.

What You’ll Hear: A Three-Act Emotional Journey

Think of this étude as a short drama in three acts.

Act One: Quiet Remembrance

The piece opens in E major, but don’t let the “major” key fool you into expecting cheerfulness. The melody floats above a bed of oscillating sixteenth notes, creating a dreamy, almost suspended feeling. Time seems to slow down. If you’ve ever sat alone with old photographs, letting memories wash over you without trying to hold onto any single one, you’ll recognize this sensation.

Pay attention to the tiny ornamental notes (grace notes) that appear. Chopin gives very specific instructions: the first should be played long and singing, the second short and light. It’s as if a wave of sadness crests and then gently recedes.

Act Two: The Storm Within

Around the middle section, something shifts. The music grows more animated (poco più animato), and suddenly we’re no longer in quiet contemplation. Harmonies become unstable. Dissonant intervals called tritones create a sense of chaos and urgency. The dynamics build toward a powerful climax where both hands thunder through parallel sixths—one of the most technically demanding passages in all of Chopin’s études.

This is the moment, according to legend, when Chopin exclaimed about his fatherland. Whether or not the story is true, the emotional logic is undeniable. All the suppressed grief, all the helpless rage at circumstances beyond control—it erupts here before exhausting itself.

Act Three: Return to Stillness

The storm passes. The original melody returns, but it sounds different now—more personal, more fragile, as if the emotional outpouring has left the music somehow changed. The piece ends quietly, fading into silence rather than making any grand concluding statement.

Listening Tips for First-Timers

If you’re new to classical music, here are some ways to approach this piece:

Start with the melody alone. On first listen, just follow the singing line in the right hand. Let everything else become background. Notice how the tune rises and falls like breathing, how it circles back on itself like a thought you can’t quite let go.

Listen for the contrast. The middle section should feel like a dramatic interruption. When the quiet opening theme returns afterward, ask yourself: does it sound the same as before, or has something changed?

Don’t worry about the “sadness.” Despite its nickname, this étude isn’t exclusively melancholic. There’s tenderness here, and beauty, and even a kind of hard-won peace. Let your own emotions guide you rather than trying to feel what you think you’re supposed to feel.

Recommended Recordings

Different pianists bring remarkably different personalities to this piece:

Arthur Rubinstein emphasizes the Polish soul of the music—there’s a particular warmth and nostalgia in his interpretation that feels deeply connected to Chopin’s heritage.

Maurizio Pollini takes a more restrained approach, letting the music’s structure speak for itself without excessive emotional underlining. His version has a crystalline clarity.

Vladimir Horowitz brings Russian-school technical brilliance with extraordinary attention to voicing—you can hear every layer of the texture distinctly.

Each interpretation is valid. Part of the joy of classical music is discovering which voices speak most directly to you.

Why This Piece Still Matters

Nearly two centuries have passed since Chopin wrote these notes in his Parisian apartment, an ocean of experience away from the Warsaw streets of his childhood. The November Uprising is now a chapter in history books. Poland has been lost and regained and lost and regained again.

Yet the Étude in E major continues to move listeners who know nothing of its historical context. That’s the paradox of great art: it emerges from intensely specific circumstances but speaks to something universal.

We all know what it means to long for something irretrievably lost. We all understand the exhaustion that comes after intense emotion, and the quiet that follows. Chopin captured these experiences in four minutes of music.

He called it the most beautiful melody he ever wrote. Nearly two hundred years later, it’s hard to argue with him.

Press play. Close your eyes. Let Chopin take you somewhere you’ve never been—and somewhere you’ve always known.