📑 Table of Contents

There’s a legend that Niccolò Paganini sold his soul to the devil. His violin playing was so impossibly virtuosic that audiences genuinely believed supernatural forces were at work. His 24th Caprice—a fiendish showpiece dripping with technical difficulty—became the sonic emblem of that Faustian bargain.

Now imagine taking that devil’s theme and flipping it upside down. Literally. What would happen?

In the summer of 1934, Sergei Rachmaninoff answered that question. And what emerged was not darkness, but a melody so achingly beautiful that it would soundtrack countless proposals, film climaxes, and tearful reunions for the next century.

This is the story of Variation 18.

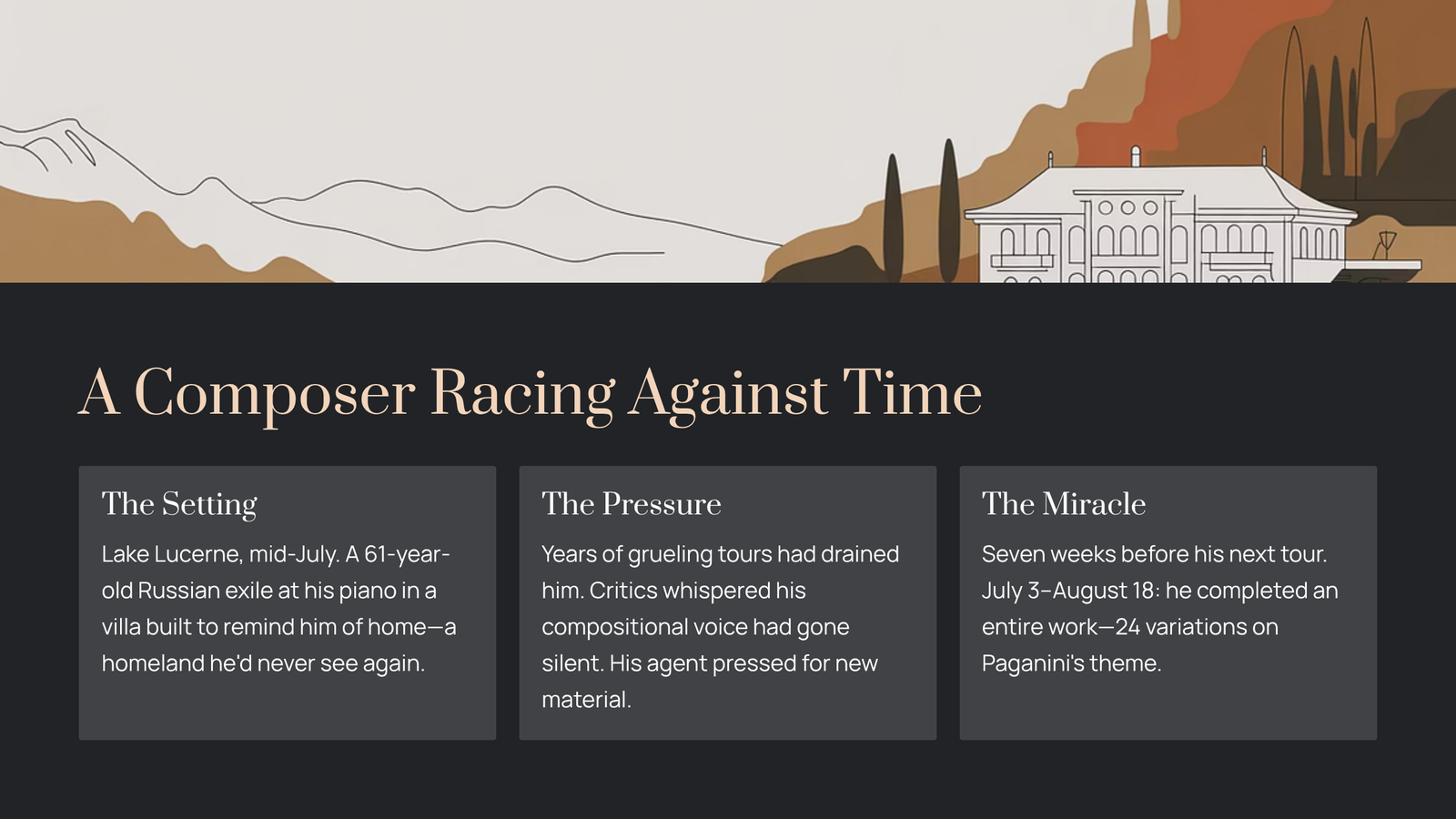

A Composer Racing Against Time

Picture Lake Lucerne in Switzerland, mid-July. A 61-year-old Russian exile sits at his piano in a villa he built to remind himself of home—a homeland he would never see again. His name is Sergei Rachmaninoff, and he is exhausted.

Years of grueling concert tours across America had drained him. Critics whispered that his compositional voice had gone silent, that he was merely a touring pianist now, living off past glories. His agent was pressing for new material—something to electrify audiences on the upcoming American season.

Rachmaninoff had seven weeks before his next tour began.

What happened next was remarkable. Between July 3rd and August 18th, in a burst of creative urgency, he completed an entire work: the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini—24 variations for piano and orchestra built on that devilish 24th Caprice.

But one variation would overshadow all others.

The Genius of the Mirror

Here’s where Rachmaninoff’s brilliance becomes almost mathematical. Paganini’s original theme moves in a specific melodic pattern—notes stepping downward in a minor key, angular and restless. It sounds driven, almost possessed.

Rachmaninoff took that melody and inverted it. Where Paganini descended, Rachmaninoff ascended. Where the original was sharp-edged and A minor, the new version bloomed into the warm, distant key of D-flat major.

The technique is called melodic inversion—a mirror image of the original. It’s the kind of thing music theory students learn in textbooks. But in Rachmaninoff’s hands, this academic exercise became something transcendent.

From the devil’s theme, love was born.

What You’ll Hear: A Listening Journey

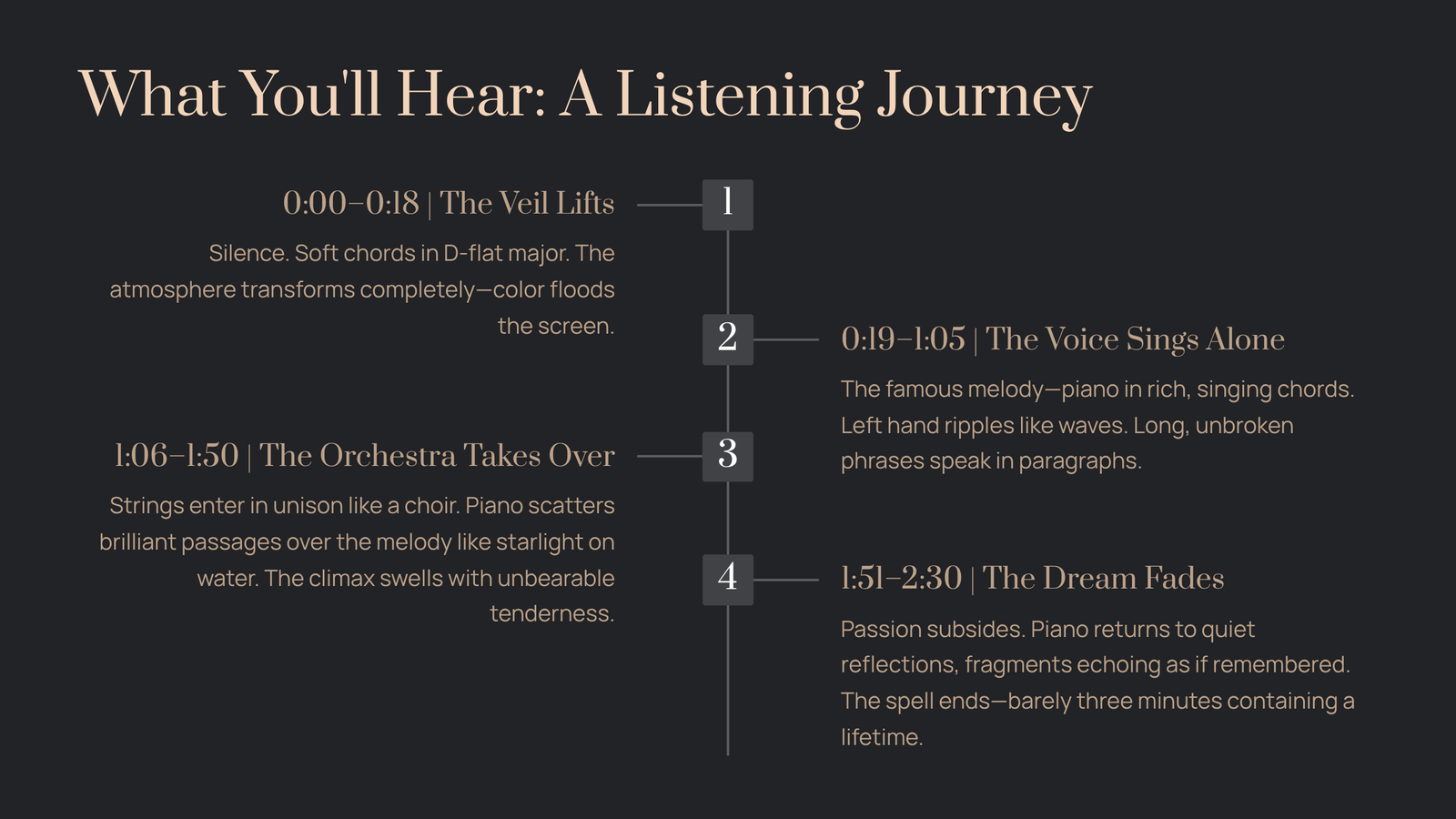

[0:00–0:18] The Veil Lifts

The preceding variation fades like a nightmare dissolving at dawn. Then silence. The piano enters with soft, spreading chords in D-flat major, and the atmosphere transforms completely. If the earlier variations were black-and-white film, this moment is when color floods the screen.

[0:19–1:05] The Voice Sings Alone

Now the famous melody appears—played by the piano in rich, singing chords. The left hand ripples through wide arpeggios, creating a sense of waves or breathing. The right hand carries the theme, each note pressed with the depth Rachmaninoff was famous for, resonating like distant church bells.

Listen for the long, unbroken phrases. This melody doesn’t speak in sentences—it speaks in paragraphs, one vast emotional arc.

[1:06–1:50] The Orchestra Takes Over

The strings enter in unison, taking up the theme like a choir finally given permission to sing. The piano doesn’t disappear—instead, it rises into the high register, scattering brilliant decorative passages over the orchestral melody like starlight on water.

This is the climax. The music swells with an almost unbearable tenderness.

[1:51–2:30] The Dream Fades

Slowly, the passion subsides. The piano returns to quieter reflections, fragments of the theme echoing as if remembered rather than played. The variation ends ambiguously, hovering—and then the 19th variation crashes in with mechanical speed, snapping us back to reality.

The spell lasts barely three minutes. But those three minutes contain a lifetime.

The Soul Behind the Notes

Rachmaninoff wasn’t just writing pretty music. In a letter to choreographer Michel Fokine—who would later create a ballet from this work—he revealed his program:

If the demonic variations represent Paganini’s bargain with the devil, Variation 18 represents what he received in return: the woman, the moment of love. It is the heart’s reward for the soul’s surrender.

But there’s another layer. Music scholars hear in this melody the voice of Rachmaninoff’s own longing—for the Russian countryside of his youth, for the estate at Ivanovka where he composed in peace, for a world erased by revolution and exile.

D-flat major, with its five flats, is one of the most enveloping keys in music. Rachmaninoff chose it not just for contrast but for its warmth, its sense of being wrapped in something soft and far away.

Recordings Worth Your Time

Rachmaninoff himself (1934): Recorded just weeks after the premiere, his own interpretation is surprisingly brisk. He doesn’t wallow in sentiment—he lets the structure speak. It’s leaner than you might expect, and fascinating for that reason.

Arthur Rubinstein: The opposite approach. Rubinstein stretches the tempo, luxuriates in every phrase, and maximizes emotional impact. If you want your heart thoroughly wrung, start here.

Yuja Wang: A modern take—crystalline clarity, technical perfection, and a refusal to over-sentimentalize. Her version feels like the melody is made of glass, beautiful and precise.

Each approach reveals something different. The music is generous enough to accommodate them all.

Why This Melody Endures

In 1980, the film Somewhere in Time used Variation 18 as its central theme—a story of love that transcends time itself, starring Christopher Reeve and Jane Seymour. The movie became a cult classic, and the music became inseparable from romantic longing in popular imagination.

But the melody didn’t need Hollywood to survive. From its very first performance in Baltimore—November 7, 1934, with Rachmaninoff at the piano and Leopold Stokowski conducting—audiences understood immediately. This was something special.

Rachmaninoff himself knew. After composing it, he reportedly joked: “This one is for my agent.” He meant it would sell tickets, fill halls, guarantee his commercial success.

He was right. But he was also, perhaps, underselling what he’d done.

He hadn’t just written a crowd-pleaser. He’d taken the devil’s melody and shown what redemption sounds like.

A Final Thought

There’s something almost alchemical about what Rachmaninoff achieved. Take a theme everyone associates with darkness and virtuosic excess. Flip it upside down. And suddenly you’re holding pure gold.

Maybe that’s the real magic of Variation 18. It reminds us that transformation is always possible. That the raw material of something harsh can become the foundation of something tender. That a composer in exile, exhausted and doubting himself, could still reach into his craft and pull out immortality.

Three minutes. One inversion. A lifetime of feeling.

Press play. Let the waves carry you.