Table of Contents

Sounds That Drift Like Questions

Some music doesn’t guide you from beginning to end. Instead, it places you in the middle of an unfamiliar room and quietly steps back. “Decide for yourself what you feel here,” it whispers. Erik Satie’s Gnossienne No. 3 is precisely that kind of music.

Unfolding across piano keys, this piece has no time signature, no bar lines. Notes simply emerge like questions and vanish without answers. From the first sound, you understand: this isn’t music to “listen to” but music to “breathe with.” Satie hasn’t handed you sheet music—he’s given you a map of emotions. That map has no destination. Only your footsteps along the path create direction.

Have you ever had this experience? Walking a familiar street when suddenly you stop and think, “Why am I here?” That moment’s mixture of stillness and unease—that’s exactly what Gnossienne No. 3 is.

The Labyrinth of Time Drawn Without Measure

Erik Satie was a composer who dreamed of revolution in 1890s Paris. Rather than building grand narratives like Beethoven’s symphonies, he wanted to erase the very framework of “time” from music. The result was his Trois Gnossiennes (Three Gnossiennes) series. Published in 1893, this collection was an unprecedented experiment in classical music history. Sheet music without time signatures. Staves without bar lines. Satie told performers: “Don’t watch the clock—listen to your heartbeat.”

The origin of “Gnossienne” remains debated. Some scholars claim it derives from ritual dances performed in the ancient Cretan labyrinth of Knossos. Others interpret it as alluding to Gnosticism’s concept of “gnosis” (knowledge). But the name’s origin isn’t what matters. What matters is that through this piece, Satie sought to recreate the experience of walking through a maze—in music.

Paris of that era witnessed the flowering of Symbolism and Impressionism. Satie earned his living playing piano in Montmartre cabarets, exploring new musical languages through exchanges with fellow composers like Debussy. Gnossienne No. 3 was born in this context—a revolutionary attempt that rejected traditional harmonic rules, deconstructed temporal flow, and invited listeners into a meditative space.

The Secret of Melody Scattered Like Fragments

Listening to Gnossienne No. 3 for the first time evokes a strange sensation. Something keeps progressing, yet simultaneously seems to circle back. Examining the piece’s musical structure gradually reveals its secrets.

The Left Hand’s Repetition, The Right Hand’s Wandering

The left hand is simple. It repeatedly presses a few notes, creating sustained tones and brief chords. Like a heartbeat, or perhaps distant bells ringing. This repetition becomes the “foundation” for the entire piece. Above it, the right hand floats freely.

The right hand’s melody is incomplete. More precisely, it refuses to be complete. The melodic line ascends like a question, descends without answering. It leaps, then pauses, then advances cautiously again. Satie called these “melodic fragments”—not finished sentences but scattered words. The silence between those words speaks volumes.

Tension Through Tonal Ambiguity

Traditional classical music has clear tonality—C major, D minor, and so on. When pieces end, they conclude with a “perfect cadence,” a stable harmonic progression that clearly announces: “It’s over.”

But Satie offers no such certainty. Gnossienne No. 3 doesn’t belong entirely to any key. Chords stack unstably, moving to the next without resolution. The ending is equally ambiguous—did it finish or not? Like placing a comma instead of a period at sentence’s end. Even after the music stops, you remain suspended in its space.

Literary Directions Hidden in the Score

Satie’s uniqueness also reveals itself in phrases scattered among the notes. “Avec étonnement” (with astonishment), “Du bout de la pensée” (from the edge of thought), “Postulez en vous-même” (question yourself). These directions don’t indicate tempo or dynamics. Rather, they’re poetic hints aimed at the performer’s inner world.

Satie considered music “philosophy expressed in sound.” His scores aren’t mere performance manuals but guides for contemplation. “When you play this note, what are you thinking?” Satie’s questions continue. Answering them is the performer’s and listener’s responsibility.

Lost Between Anxiety and Serenity

When I first heard this piece, I recalled a moment gazing out a window late at night. Darkened streets, tree-branch shadows swaying beneath streetlights. A feeling that something exists though no one’s there. Not frightening, but not comfortable either—that emotion.

Gnossienne No. 3 exists precisely at that boundary. Between serenity and anxiety. Meditative yet tense, quiet yet something stirs beneath. Listening to this piece brings your hidden, ambiguous emotions to the surface. Feelings without names. Memories beyond words.

Satie asks you: “What are you feeling right now?” And he doesn’t demand an answer. He simply stands you before that question. Some find peace in this music, others feel sadness. Still others experience only the emptiness of time suspended. All responses are valid. Because this music is a mirror—showing you what you want to see.

For me, this piece taught “the beauty of incompleteness.” Not everything needs perfect resolution. Sometimes questions alone suffice. Unanswered questions lead to deeper contemplation. Satie already knew: music’s greatest gift isn’t clear answers but the courage to ask questions.

Three Keys to Listening Deeper

One reason classical music appreciation feels difficult is uncertainty about “how to listen.” This is especially true for iconoclastic composers like Satie. But knowing a few key points makes Gnossienne No. 3 a far richer experience.

First Key: Follow the Left Hand’s Repeated Notes

While listening, focus on the left hand’s lower notes. Those repeating sounds are like time’s pulse. No matter how freely the right hand’s melody drifts, the left hand steadfastly holds its place. Consciousness of this contrast makes the piece’s structure clearer. Left hand is earth, right hand is sky. Music breathes between them.

Second Key: Trust the Value of Repeated Listening

Gnossienne No. 3 isn’t music understood in one hearing. The second time brings different feelings than the first; the tenth reveals yet another layer. This piece is like an onion—the more you peel, the more emerges. Don’t rush. Listen multiple times. Depending on your mood, this music will show a different face each time.

Third Key: Compare Multiple Performances

Countless pianists have recorded Satie’s Gnossienne No. 3. Pascal Rogé’s performance is gentle, emphasizing space. Alessio Nanni maximizes the piece’s mystique through dramatic contrast. Kai Schumacher delicately renders empty space with transparent tone. The same piece becomes completely different music depending on the performer. Comparing versions and finding the interpretation you most connect with is a valuable experience.

One more thing: when listening to this piece, use headphones or good speakers if possible. Satie’s music lives in small nuances—the subtle resonance of chords blending when pedal is pressed, shifts in finger weight pressing keys. These details gather to create Gnossienne No. 3‘s true magic.

From Labyrinth to Prelude – Bach’s Next Journey

Having experienced the suspended-time labyrinth of Satie’s Gnossienne No. 3, let’s now step into a musical world where time flows with clarity. That would be Johann Sebastian Bach’s Prelude in C major, BWV 846—the first piece in The Well-Tempered Clavier Book I, and one of classical piano’s most famous preludes.

If Satie erased meter and deconstructed time, Bach did the opposite—designing time with perfection. The C major prelude flows from beginning to end with unbroken waves of sixteenth notes. Like clear spring water babbling forth, arpeggios (broken chords) continue without a single waver.

If Gnossienne No. 3 is music that questions, Bach’s C major prelude is music that affirms. Clarity replaces ambiguity, stability replaces instability. Yet simultaneously, hidden within this seemingly simple prelude lies a remarkable harmonic journey. Chords change with each measure, and drama unfolds through those changes.

If you found the experience of feeling lost in Satie’s labyrinth captivating, Bach’s prelude will show you a different kind of beauty. Freedom within order, complexity within simplicity. The two composers explored music’s essence through opposite methods. Experiencing both worlds is classical music’s greatest gift.

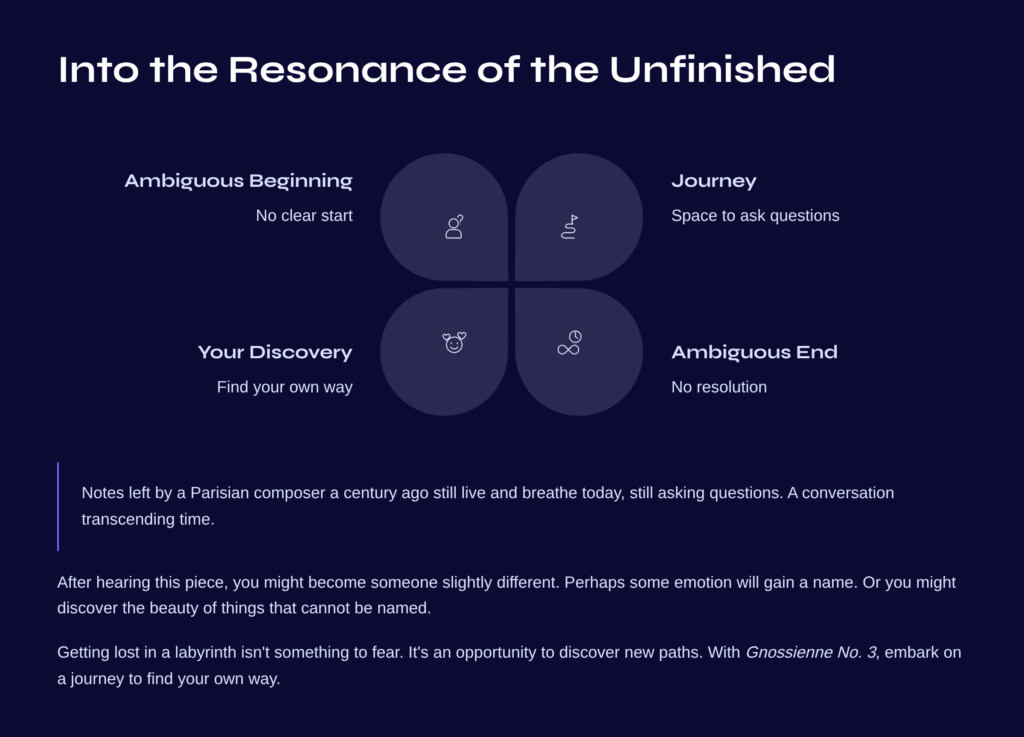

Into the Resonance of the Unfinished

Ultimately, Gnossienne No. 3 isn’t a completed story. Something with ambiguous beginning and end. But precisely that ambiguity is this piece’s power. Satie doesn’t give you answers. Instead, he offers space to ask questions.

After hearing this piece, you might become someone slightly different. Perhaps some emotion within you will gain a name. Or conversely, you might discover the beauty of things that cannot be named.

This is why music is great: notes left by a Parisian composer a century ago still live and breathe in your room, in your ears today, still asking questions. A conversation transcending time. That’s classical music’s magic, and Satie’s gift to us.

Getting lost in a labyrinth isn’t something to fear. Rather, it’s an opportunity to discover new paths. With Gnossienne No. 3, embark on a journey to find your own way.