📑 Table of Contents

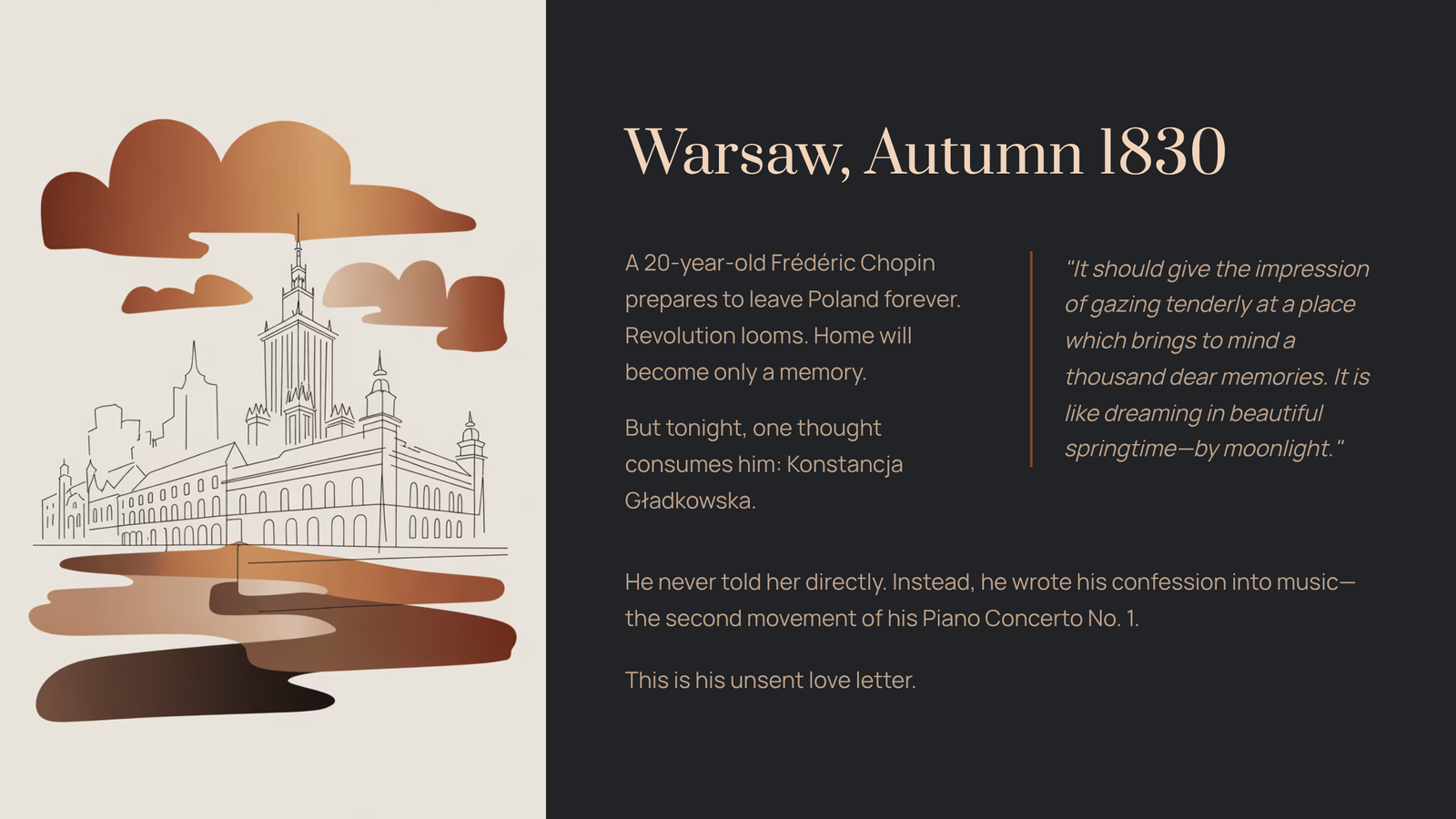

In the autumn of 1830, a 20-year-old Frédéric Chopin sat in his room in Warsaw, preparing to leave Poland forever. He didn’t know it yet—that he would never return, that revolution would sweep through his homeland, that he would die in Paris nineteen years later, still longing for home.

But on that night, something else occupied his thoughts entirely: a woman named Konstancja Gładkowska.

He had never told her how he felt. Not directly. Instead, he did what only a composer could do—he wrote his confession into music, hiding it in the second movement of his Piano Concerto No. 1. In a letter to a friend, he admitted: “It is not meant to be loud, it’s more of a romance, calm, melancholic—it should give the impression of gazing tenderly at a place which brings to mind a thousand dear memories. It is like dreaming in beautiful springtime—by moonlight.”

This is that movement. This is his unsent love letter.

Who Was Konstancja?

Konstancja Gładkowska was a young soprano studying at the Warsaw Conservatory. Chopin, shy and prone to intense but unexpressed emotions, admired her from a distance for months. He attended her performances, wrote about her obsessively in letters to friends, but could never bring himself to confess directly.

Their relationship remained ambiguous—warm but undefined. And when Chopin left Warsaw in November 1830, just weeks after completing this concerto, he carried only two things from her: a ribbon she had given him and this music, soaked in everything he couldn’t say aloud.

Konstancja later married someone else. Chopin never forgot her.

What Makes This Movement So Intimate

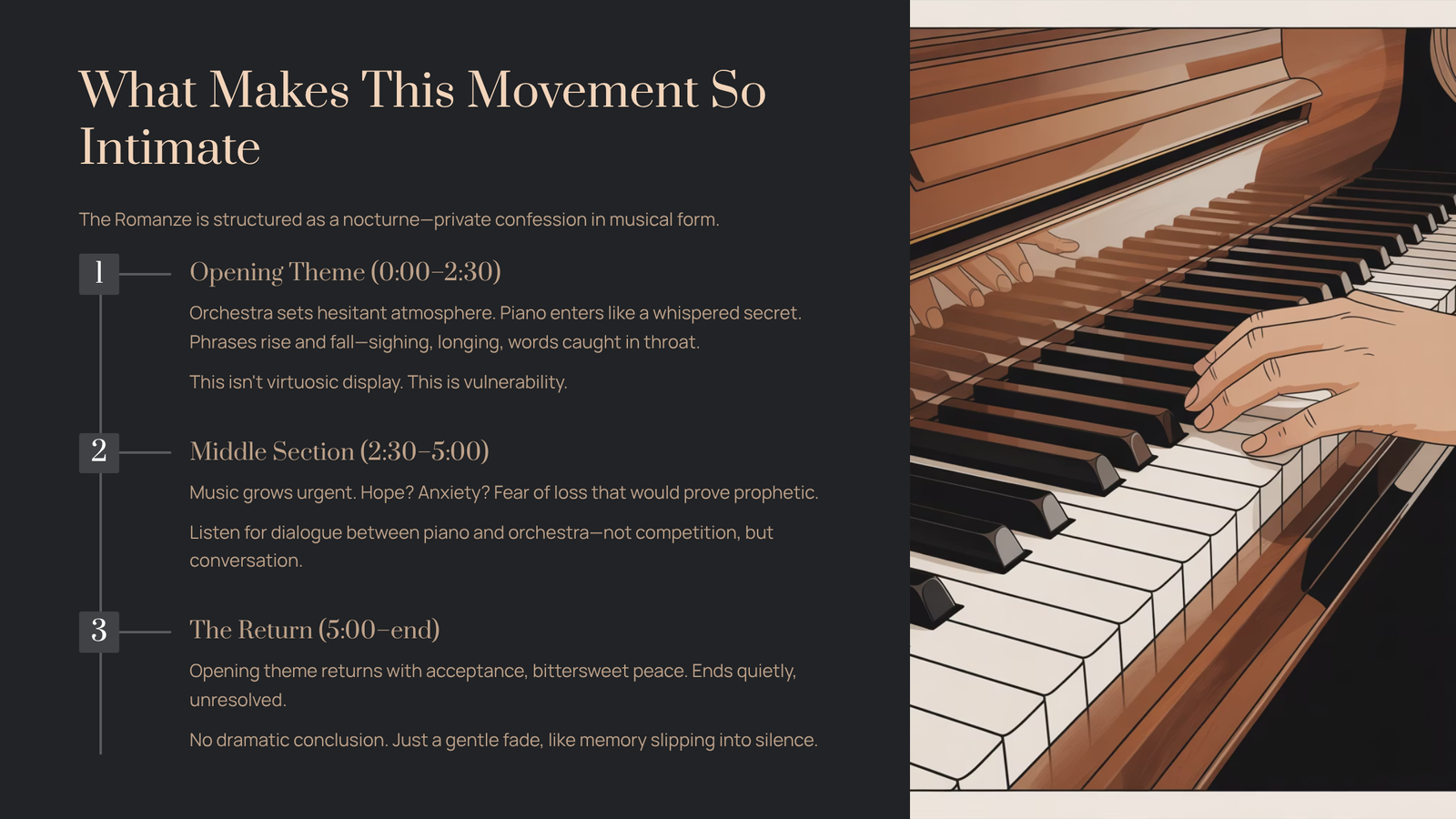

The Romanze is structured as a nocturne—a form Chopin would later perfect and make famous. But here, in his concerto, the nocturne style serves a specific purpose: private confession.

The Opening Theme (0:00–2:30)

The orchestra sets a gentle, almost hesitant atmosphere before the piano enters. When it does, the melody unfolds like a whispered secret. Notice how the piano seems to breathe—the phrases rise and fall with the rhythm of sighing, of longing, of words caught in the throat.

This isn’t virtuosic display. This is vulnerability.

The Middle Section (2:30–5:00)

Here, the music grows more animated, more urgent. Some pianists interpret this as a moment of hope—perhaps Chopin imagining a future where he could speak his feelings. Others hear anxiety, the fear of loss that would prove prophetic.

Listen for the dialogue between piano and orchestra. It’s not a competition; it’s a conversation. The orchestra supports, responds, echoes—like the understanding friend Chopin poured his heart out to in letters.

The Return (5:00–end)

The opening theme returns, but something has shifted. There’s acceptance now, a bittersweet peace. The movement ends quietly, unresolved in the way that real emotions often are. No dramatic conclusion. Just a gentle fade, like a memory slipping back into silence.

How to Listen: Three Approaches

First Listen: Pure Surrender

Don’t analyze. Don’t think about structure or history. Find a quiet space—late evening works best—and simply let the music wash over you. This is how Chopin intended it: “dreaming in beautiful springtime, by moonlight.”

Second Listen: Follow the Conversation

Pay attention to the interplay between piano and orchestra. The strings often carry a counter-melody that responds to the piano’s statements. It’s like overhearing two people who understand each other without needing to explain.

Third Listen: The Letter Reader

Imagine you’ve found an old letter in an attic, written by someone long dead to someone they loved. The ink is faded, some words are illegible, but the emotion is unmistakable. That’s what this movement is—a document of human feeling, preserved in sound.

Recommended Recordings

For First-Time Listeners: Krystian Zimerman with Polish Festival Orchestra

Zimerman, himself Polish, brings an authenticity and tenderness to this movement that few can match. He both plays and conducts, creating an unusual intimacy between soloist and ensemble. The tempo is unhurried, giving every phrase room to breathe.

For Emotional Depth: Martha Argerich with Montreal Symphony

Argerich’s interpretation is more spontaneous, more impulsive. Where Zimerman is moonlight, Argerich is candlelight—flickering, alive, unpredictable. Her Romanze feels less like a memory and more like the moment itself, happening in real time.

For Historical Perspective: Arthur Rubinstein with London Symphony

Rubinstein recorded this concerto multiple times across his long career. His later recordings carry the weight of a life lived, of losses understood. When he plays the Romanze, you hear not just Chopin’s longing, but something universal about love and time.

A Final Thought

There’s a particular kind of sadness in loving someone you can never quite reach—whether separated by circumstance, timing, or simply the inability to find the right words. Chopin knew this sadness intimately, and he transformed it into something we can still feel nearly two centuries later.

The Romanze isn’t just about Konstancja Gładkowska. It’s about every confession we’ve held back, every feeling we’ve buried because we didn’t know how to speak it. Chopin found a way to speak without words, and he left that language for us.

Next time you hear this movement, remember: you’re not just listening to music. You’re reading someone’s heart.

What emotions does this piece bring up for you? There’s no wrong answer—only your answer.