📑 Table of Contents

Some of the most beautiful things in life happen by accident. The melody you’re about to discover was born from a twist of fate involving two giants of classical music—and a poet caught between them.

In 1827, the German poet Ludwig Rellstab sent a collection of his verses to Ludwig van Beethoven, hoping the master would set them to music. But Beethoven died before he could even read them. The poems sat forgotten among his belongings until his secretary, Anton Schindler, discovered them while sorting through the estate. Rather than let them gather dust, Schindler passed them to another composer living in Vienna—a 31-year-old man who had only months left to live.

That man was Franz Schubert. And one of those poems became Ständchen—what many consider the most perfect serenade ever written.

The Man Behind the Music

Franz Schubert was never a celebrity in his lifetime. Unlike Mozart’s child prodigy fame or Beethoven’s dramatic public persona, Schubert lived a quiet, often financially precarious existence. He wrote over 600 songs, yet struggled to get them published. He hosted intimate gatherings called “Schubertiades” where friends would gather to hear his latest compositions, but major concert halls remained largely closed to him.

By the summer of 1828, Schubert was seriously ill. Suffering from what historians believe was syphilis complicated by typhoid fever, he had moved into his brother Ferdinand’s apartment on the outskirts of Vienna. The rooms were cramped and damp—hardly ideal for a sick man. Yet it was here, in these final months, that Schubert poured out some of his most profound music.

When he received Rellstab’s poems from Schindler, something in the verses about moonlit nights and whispered longing must have resonated deeply. Between August and October of 1828, Schubert set seven of Rellstab’s poems to music. He would die on November 19th—just weeks after completing them.

What Makes This Serenade So Special

Close your eyes and imagine a warm summer night. Someone stands beneath a window, guitar in hand, singing to the person they love. This image—the classic serenade—is exactly what Schubert captures, but with a depth of emotion that transforms a simple romantic gesture into something universal and timeless.

The piano doesn’t just accompany the singer; it becomes a guitar. Throughout the entire piece, the pianist plays a distinctive pattern of plucked-sounding triplet chords. It’s a technical detail, but listen for it—those gentle, repeated notes create the illusion of strings being strummed under a moonlit sky.

But here’s where Schubert’s genius reveals itself. The song begins in D minor, a melancholy key. The lover’s plea carries an undertone of uncertainty, even pain. Then, in the final verse, something magical happens: the music shifts to D major. It’s like the clouds parting to reveal the moon. The same melody that sounded wistful now glows with hope.

This transformation from darkness to light—from longing to fulfillment—happens in the span of a few measures. Schubert achieves what would take a novelist chapters to accomplish.

A Listening Guide for First-Timers

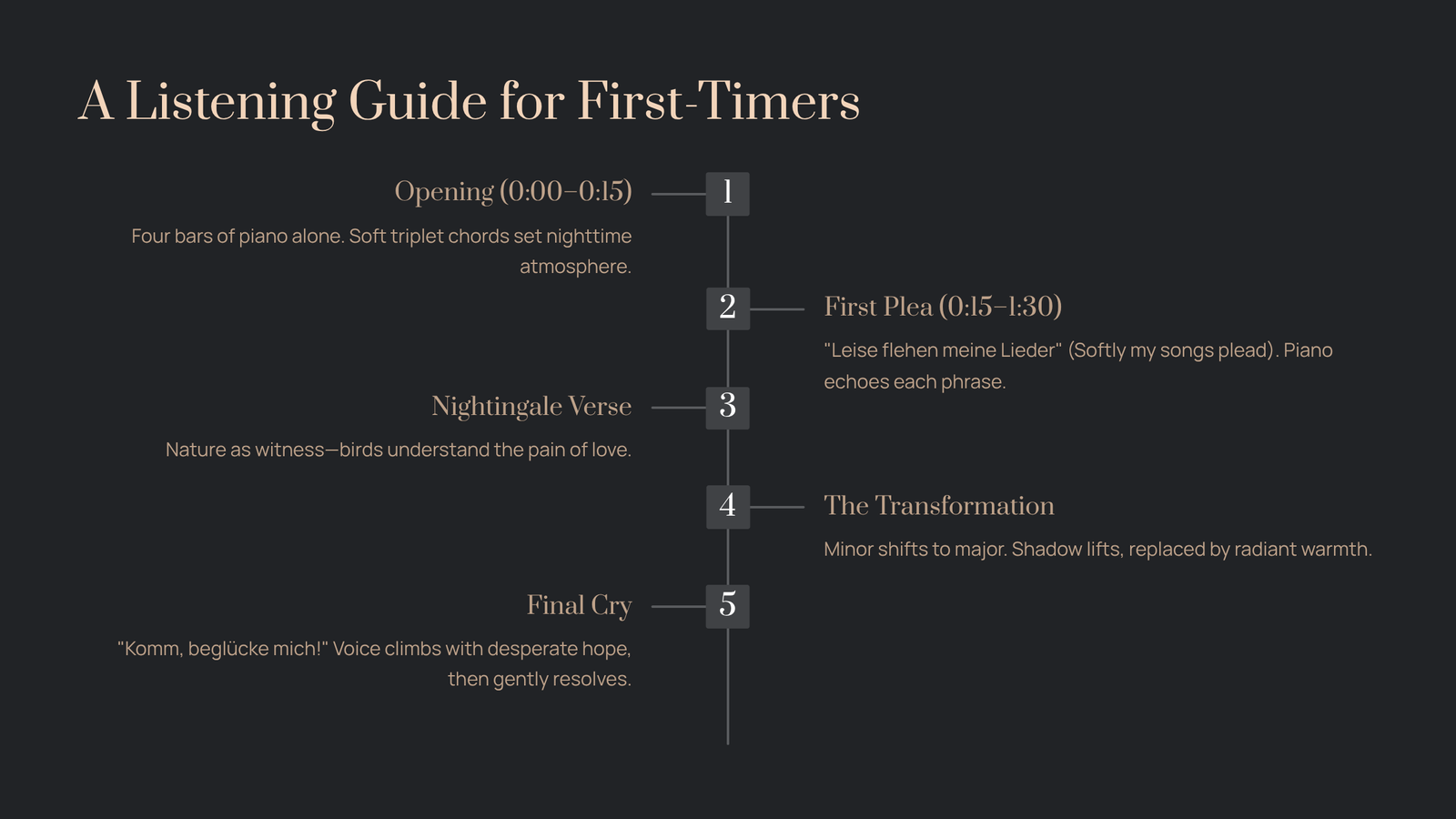

You don’t need to read music to appreciate this piece. Here’s what to listen for:

The Opening (0:00–0:15): Four bars of piano alone set the scene. Those soft, repeated triplet chords establish the nighttime atmosphere before a single word is sung.

The First Plea (0:15–1:30): The singer enters with “Leise flehen meine Lieder” (Softly my songs plead). Notice how after each vocal phrase, the piano echoes the melody’s tail end—like the song reverberating through the night air, or perhaps the lover waiting for a response that doesn’t come.

The Nightingale Verse: The second stanza brings imagery of nightingales and whispering trees. Rellstab draws on classic Romantic symbols—nature as a witness to human emotion. The singer tells us the birds understand the pain of love.

The Transformation: This is the moment to watch for. When the text speaks of the beloved’s heart being moved, the music shifts from minor to major. That shadow of sadness lifts, replaced by radiant warmth. It’s brief and precious—and all the more moving for it.

The Final Cry: “Komm, beglücke mich!” (Come, make me happy!) The song reaches its emotional peak, the singer’s voice climbing with desperate hope. Then the piano gently winds down, leaving us in that D major glow—as if the window has finally opened, or perhaps as if we’ve drifted into a beautiful dream.

The Hidden Tension You Might Miss

There’s a subtle musical conflict running through Ständchen that creates its sense of restless yearning. The piano plays triplets—three notes per beat. The vocal line often moves in different rhythmic groupings. These two patterns don’t quite align, creating a gentle friction that mirrors the emotional state of someone who can’t rest until they know if their love is returned.

It’s the musical equivalent of a racing heart, of lying awake at 3 AM thinking about someone. Schubert found a way to make us feel longing through pure rhythm.

Recordings Worth Your Time

This song has been recorded countless times by artists across generations. Here are some interpretations that offer different windows into the music:

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau with Gerald Moore represents the scholarly gold standard—every word weighted with meaning, every phrase perfectly shaped. His baritone brings gravitas to the lover’s plea.

Ian Bostridge offers a more febrile, almost feverish interpretation. His tenor adds vulnerability, making the serenade feel genuinely urgent rather than merely beautiful.

For something different, seek out Franz Liszt’s piano transcription (S. 560, No. 7). The legendary pianist-composer reworked this song for solo piano, splitting the vocal melody across multiple voices while maintaining the guitar-like accompaniment. It’s technically demanding and emotionally overwhelming—Liszt essentially created a one-man opera.

The Afterlife of a Masterpiece

Schubert never heard his final songs performed publicly. The collection was published in May 1829, six months after his death, by the Viennese publisher Tobias Haslinger. It was Haslinger who gave the collection its poetic title: Schwanengesang—”Swan Song”—referencing the legend that swans sing their most beautiful melody just before death.

The song has since woven itself into popular culture in surprising ways. Players of the indie video game SIGNALIS will recognize it as a crucial narrative element. Online music communities have noted intriguing harmonic similarities between Ständchen and the opening theme of HBO’s Succession—whether deliberate homage or coincidence remains debated.

One small caution for those exploring Schubert’s catalog: he wrote another song also titled “Ständchen” (D. 889), set to Shakespeare’s text “Hark, hark, the lark!” That one is a cheerful morning song—quite different in character from this nocturnal masterpiece.

Why This Song Still Matters

Two centuries after Schubert’s death, Ständchen continues to move listeners because it captures something eternally true about human desire. We all know what it feels like to want something—or someone—deeply, to stand outside a metaphorical window hoping to be let in.

The German word Sehnsucht has no perfect English translation. It means longing, but also yearning for something you may never reach—a bittersweet ache for the unattainable. This is the emotional territory Schubert maps with such precision.

That a dying man could create something so full of hope and tenderness tells us something profound about the human spirit. Schubert knew his time was short. Yet instead of despair, he gave us beauty.

The poem Beethoven never read became the song Schubert was born to write. Sometimes the accidents of history produce miracles.