Table of Contents

A Moment of Silent Farewell

Sometimes distancing ourselves from the world is the only way to find our true selves. In the noise of our busy daily lives, we often lose our authentic voice. Mahler’s “Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen” (I Am Lost to the World) captures exactly such a moment—a journey toward discovering one’s inner sanctuary through a quiet farewell to the world.

Every time I listen to this piece, I’m reminded of how precious solitude can be. It’s like walking alone through crowded city streets, yet that solitude doesn’t feel lonely—rather, it brings a sense of profound peace.

A Small Miracle by Lake Wörth

Gustav Mahler composed this song on August 16, 1901, by the shores of Lake Wörth in Maiernigg, Carinthia, Austria. Each summer, he would retreat to his lakeside villa, working alone in his small composing hut from 6 AM through the morning hours. His Symphonies 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 were all born in this modest sanctuary, making it not merely a summer retreat but a refuge for his soul.

His encounter with Friedrich Rückert’s poetry was surely no coincidence. This linguistic genius, who mastered thirty languages, wrote the poetry collection “Liebesfrühling” (Spring of Love) in 1821 for his beloved, and “Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen” was among these verses. As a professor of Oriental languages and a cultural bridge between East and West, Rückert’s poetry must have resonated deeply with Mahler, who wandered the world communicating through the universal language of music.

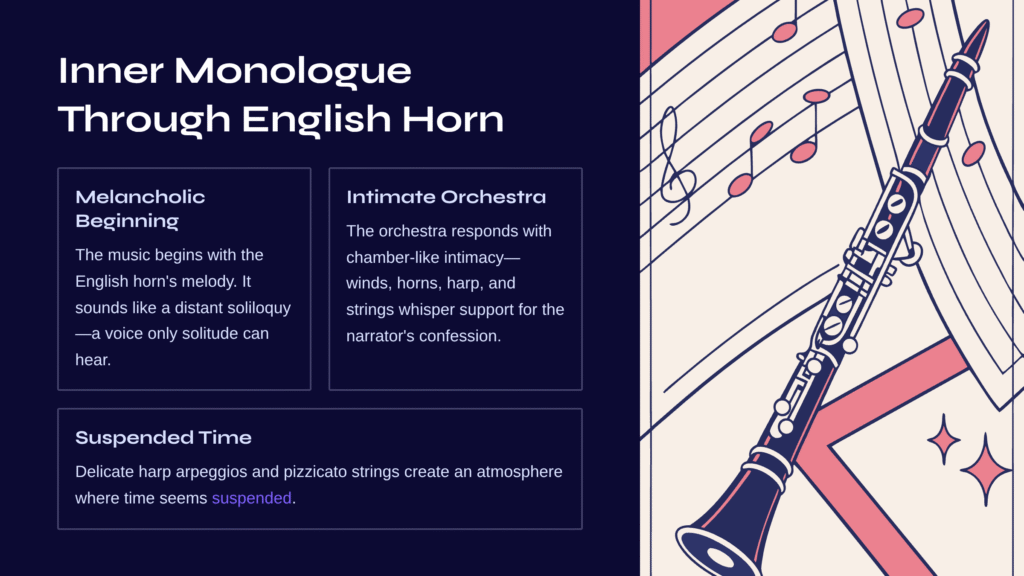

Inner Monologue Through English Horn

The music begins with the melancholic melody of the English horn. Its voice sounds like someone’s distant soliloquy—a voice that only solitude can hear, emanating from the deepest recesses of the soul.

Though Mahler structured this song in ABA form, the emotional flow matters more than the formal architecture. In the first stanza, the narrator calmly confesses his farewell to the world: “I am lost to the world, with which I used to waste much time.” The orchestra responds with chamber music-like intimacy—double winds (except flute), English horn, two horns, harp, and full strings whisper their support for the narrator’s confession.

The second stanza becomes even more intimate. “I am dead to the world’s tumult, and rest in a quiet realm.” Here, Mahler interprets “death” not as literal death but as liberation from worldly concerns. The delicate arpeggios of the harp and pizzicato strings create an atmosphere where time itself seems suspended.

The final stanza reaches its climax: “I am dead to the world, and rest in my heaven.” The English horn and vocal line engage in dialogue, like two voices offering mutual comfort. In this moment, Mahler’s special gift for “expressing complex emotions through seemingly simple melodic lines” truly shines.

Music That Became Mahler Himself

Mahler said of this song, “It is truly me.” Within that confession lies the complete portrait of an artist alienated from the secular world. For Mahler, who daily battled the weight of reality as director of the Vienna Court Opera, this song represented the only doorway to his private inner world.

Fascinatingly, the melodic material of this song is intimately connected to the Adagietto movement of Mahler’s Symphony No. 5. Both works were composed during the same period (1901-1902) at Maiernigg, and the famous Adagietto melody shares motivic similarities with this song. While some interpret the Adagietto as a wordless love letter to Alma Schindler, who would become his wife, musically it shares the same emotional territory of solitude and alienation as this song.

Finding Your Own Heaven

To properly appreciate this piece, focus on several key elements. First, listen carefully to the English horn’s introduction. Notice how this melody later dialogues with the vocal line and interweaves with other orchestral instruments.

Second, experience Mahler’s characteristic “chamber-like orchestration.” Though famous for his massive symphonies, here Mahler achieves maximum emotional impact with minimal instrumental forces. Feel how clearly each instrument speaks and how they combine into perfect harmony.

Finally, don’t underestimate the value of repeated listening. This isn’t music that reveals itself in a single hearing. Each listening unveils new layers of meaning, and the work speaks differently depending on your life experiences. Comparing various interpretations by masters like Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau or Thomas Hampson will enrich your appreciation immensely.

Comfort That Transcends Time

It’s no coincidence that during the pandemic, many people found special solace in this piece. Elīna Garanča’s performance at the 2020-2021 Salzburg Festival moved audiences worldwide. In forced isolation from the world, Mahler’s music showed that such separation could become an opportunity for inner growth rather than mere loneliness.

“Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen” is ultimately not a song of loss but of discovery. It’s a paradoxical journey where losing the world leads to finding oneself, where moving away from noise allows us to hear our true voice. This must have been the truth Mahler discovered in his small Maiernigg hut.

When the music ends, we must return to the world. But for those precious moments, we can rest in our own inner sanctuary, maintaining distance from worldly concerns. This is Mahler’s small miracle to us. Like that consoling melody that still resonates across time, we can believe that each of us carries within our hearts a quiet heaven to which we can always return.

Next Musical Journey: Grieg’s Elegy

After experiencing Mahler’s inner stillness, why not encounter another Nordic composer’s meditative moment? Edvard Grieg’s “Elegy” from his Lyric Pieces offers a different quality of sorrow and longing from Mahler’s song.

The deep Norwegian sentiment painted by a single piano contrasts with Mahler’s orchestral inner landscape while mysteriously connecting to it. Grieg’s characteristic folk melodies and harmonies create nostalgia not for the solitude of one who has left the world, but for homeland and vanished time.

Experiencing Grieg’s lyrical purity after Mahler’s philosophical depths feels like returning to nature’s embrace after deep meditation. Both composers sang of time’s passage and life’s transience in their own ways, but their sonic colors are entirely different. Sensing this difference adds another dimension to the joy of classical music appreciation.