Table of Contents

A Small Whisper the Night Delivers

Some music chooses its time. There is music for morning, music for midday, and music for night. Grieg’s Notturno, Op. 54 No. 4, is unmistakably music of the night. But this night is not beneath salon candlelight like Chopin’s nocturnes—it unfolds in the crisp air of Norwegian mountain ranges.

When I first listened to this piece seated at the piano, I felt a strange sense of floating. As if my feet weren’t touching the ground, the rhythm created by the 9/8 meter was neither walking nor running, but some movement in between. It was like footsteps in a dream. Have you ever had such a dream? Those moments when you step forward but the ground gradually moves away, and the air feels like water.

In 1891, the inspiration Grieg received while hiking the Jotunheimen mountains seeped into this piece. He sought to capture not the night of cities but the night of nature, not artificial darkness but the stillness beneath starlight.

A Great World Within a Small Piece – The Lyric Pieces and Grieg’s Musical Language

Edvard Grieg composed 66 “Lyric Pieces” throughout his lifetime. Completed over nearly 35 years from 1867 to 1901, these works can be considered his musical autobiography. Each piece is a brief miniature of 3-4 minutes, yet within them are condensed the nature and folk music of Norway, along with Grieg’s distinctive lyricism.

The Notturno is the fourth piece in Book V of the Lyric Pieces, Op. 54. By this period, Grieg had already entered his fifties, and his musical language had reached the pinnacle of maturity. What’s fascinating is that this piece shares a remarkably similar atmosphere to Debussy’s “Clair de Lune,” composed in the same year. Though the two composers didn’t know each other, they were simultaneously exploring the new direction European music was taking at the end of the 19th century—impressionistic colors and expanded harmony.

Grieg’s nocturne follows Chopin’s tradition yet is distinctly different. Here dwells not Polish melancholy but Norwegian coolness, not salon elegance but natural simplicity. Despite choosing the bright key of E major, the atmosphere enveloping the entire piece is dreamlike and introspective.

Night Landscape Painted in Sound – Musical Structure and Characteristics

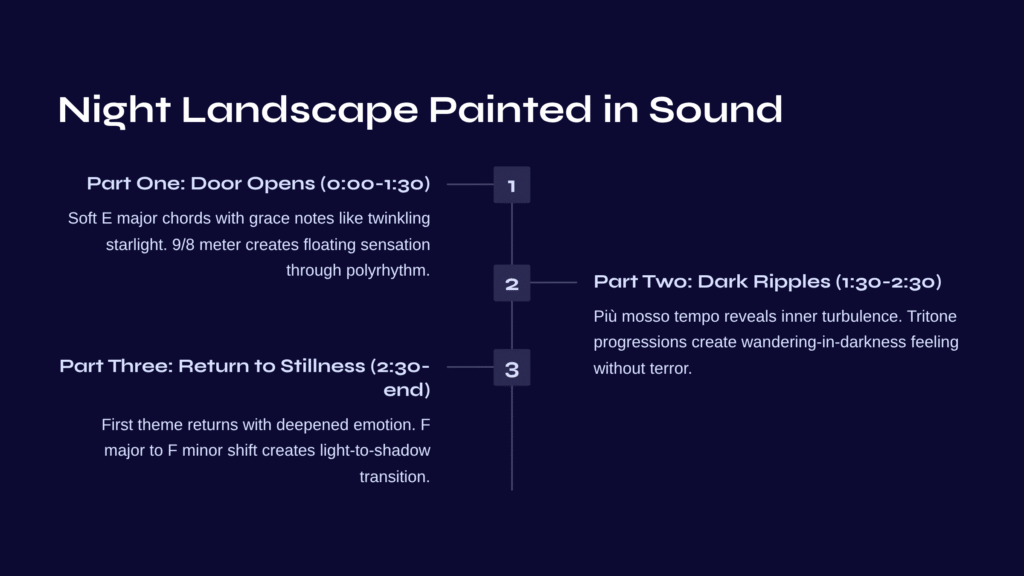

This piece follows a typical ternary form (A-B-A’), but the musical journey unfolding within is far from simple.

Part One: The Door of Night Opens (0:00-1:30)

The piece begins with soft E major chords. Above the bass line of perfect fifths created by the left hand, the right hand’s melody unfolds cautiously. Small grace notes are attached to this melody, creating tiny tremors in the music like twinkling starlight.

Here, the role of the 9/8 meter is crucial. Unlike the familiar 3/4 or 4/4 time, the 9/8 meter creates moments that feel irregular—not 3+3+3 division, but patterns like 2+2+2+3 or 3+2+2+2. Grieg uses syncopation within this meter, making the rhythm flow even more fluidly. The listener cannot pinpoint exactly where the strong beat lies, making the music feel as if it’s floating on water.

The 2:3 polyrhythm created between the left and right hands reinforces this floating sensation. When the left hand plays two notes, the right hand plays three, and this subtle mismatch simultaneously creates tension and relaxation in the music.

Part Two: Ripples in the Darkness (1:30-2:30)

Entering the middle section, the tempo marking changes to “Più mosso (more quickly).” Here the music escapes from its initial quietness and reveals a kind of inner turbulence. Double-note passages suggesting bitonality appear in the right hand, sounding as if two different keys are ringing simultaneously.

Grieg employs the tritone progression technique here. The tritone is the most unstable interval in the diatonic scale, once called the “devil’s interval” in medieval times. The tension this interval creates demands resolution, but Grieg continually postpones and avoids that resolution. Thanks to this, this section evokes feelings of wandering in darkness, of being lost.

Yet this is not terrifying darkness. Rather, it’s closer to the wonder of exploring an unknown world, of standing before unknowable beauty. The more unstable the harmony, the sweeter the moment of resolution feels.

Part Three: Back Into Stillness (2:30-end)

The first theme returns. But this is not simple repetition. It’s the same melody but with deepened emotion, reimagined through eyes that have experienced more. Grieg uses a remarkable harmonic shift here—the transition from F major 7th to F minor 7th chord.

In this moment, the music subtly changes color, as if moving from light to shadow, from laughter to tears. But this is not sadness—it’s closer to resignation, or acceptance. The quiet acknowledgment of someone who knows that night doesn’t last forever, that all beautiful moments pass.

The piece ends quietly in E major, but this E major is not the same color as the beginning. It’s more transparent, clearer, sounding as if it comes from farther away.

What I Felt in This Piece

Every time I listen to this piece, a specific image comes to mind. A Norwegian summer night, during the white nights when the sun doesn’t fully set. The sky is still bright but the air is cold, and the silhouette of mountain ranges hangs on the horizon. A person walking alone through that landscape. They’re not going anywhere in particular, not searching for anything. Just walking.

The emotion this piece gives is solitude, but not loneliness. It’s rather a necessary solitude, the peace that comes from time alone. Living in the modern world, we are constantly connected, constantly under pressure to do something. But this music allows us to step away from all that and return to a state of simply “being.”

Even the unstable harmonies in the middle section feel to me not like threats but like exploration. Sometimes we need to be in uncertainty. A life where everything is clear and stable is not life but stasis. Grieg’s harmonic adventures seem to translate precisely that uncertainty into music.

And finally, the emotion when the theme returns. I want to call it “homecoming.” The relief you feel when you return home after a journey, or when you lie in bed after a long day. But at the same time, we know. That tomorrow we must go out again, that this peace is temporary. That’s why the ending of this music is both sad and beautiful.

Three Points for Deeper Listening

First, pay attention to the use of the pedal. In piano, the pedal is not merely a tool to lengthen sound. It is an instrument that mixes harmonies, creates colors, and generates spatial sense. The pedal is particularly important in this piece, making the flow of 9/8 time natural and smoothly connecting subtle harmonic changes. A good performance is one where the pedal ‘isn’t heard’ yet envelops the entire music.

Second, compare different performers’ interpretations. Emil Gilels’ 1974 recording is a historic masterpiece of this piece, and in his performance you can feel the depth and coloristic sense of Russian pianism. In contrast, Leif Ove Andsnes recorded on the piano from Grieg’s home, and this historic instrument’s sound offers a more intimate and rustic tone different from modern pianos. Norwegian pianist Håkon Austbø’s performance naturally conveys folk sentiment, while Eva Knardahl’s performance is delicate and transparent. Comparing the same score through different souls’ interpretations is one of classical music’s greatest pleasures.

Third, listen repeatedly. This is not music that can be understood in one listening. At first, it might sound merely like a beautiful melody, but with repeated listening, the hidden structure, intention, and emotional textures within begin to reveal themselves. On some days, the first part will sound more beautiful; on others, the tension of the middle section will feel more intense. Music is not fixed in the score but is a living organism that comes alive differently each time, depending on the listener’s state.

A Song of Night Beyond Time

More than 130 years have passed since Grieg wrote this piece, yet this music hasn’t aged at all. Rather, it feels like music we need even more in this moment, in 2025. In a world that demands only speed and efficiency, productivity and results, this music whispers to us to pause for a moment, to look at ourselves in the stillness of night.

This nocturne, inspired by the Norwegian mountains, ultimately sings of universal human emotions. Solitude and peace, anxiety and acceptance, journey and return. All of this is contained within about four minutes of music. Grieg didn’t write grand symphonies or operas, but he captured the universe in these small miniatures.

Tonight, why not turn off the lights in your room and listen to this music? The sound flowing from the speakers will transform your room into a Norwegian night. And you will understand what it means when we say music transcends time and space.

Next Journey: Tchaikovsky’s Dumka, Op. 59

Having experienced Grieg’s lyrical night, it’s time to journey to another night of Eastern Europe. Tchaikovsky’s Dumka, Op. 59 is a work inspired by Ukrainian folk music, offering a unique world where Slavic sentiment combines with Russian Romanticism.

The title “Dumka” derives from the Ukrainian word “дума (duma),” meaning “thought” or “meditation.” This genre traditionally features a form where slow, melancholic melodies alternate with fast, passionate dance rhythms. Tchaikovsky expressed his deep inner world through this 1886 work, where his personal anguish and artistic maturity achieve an exquisite balance.

If Grieg’s Notturno painted the cool night sky of Northern Europe, Tchaikovsky’s Dumka sings of the vastness of the Russian land and the depth of the Slavic soul. Both are “music of the night,” but the colors of these nights are completely different. If Grieg’s night is quiet and meditative, Tchaikovsky’s night is passionate and turbulent.

When listening to the Dumka, pay attention to the dramatic emotional shifts that run through the entire piece. The melancholic melody heard in the slow introduction contains the full sentiment of Russian folk songs, and the contrast when this suddenly explodes into fast dance rhythms is overwhelming. This journey oscillating between emotional extremes is the true charm of the Dumka.

Particularly, the variations appearing in the middle section demonstrate Tchaikovsky’s genius compositional technique. The process of the same theme being reborn in various forms with different tonalities, rhythms, and textures is like observing the various facets of a single person. If Grieg captured the stillness of nature, Tchaikovsky translated the complexity of human emotion into music.

Recommended recordings include Vladimir Horowitz’s passionate interpretation and Sviatoslav Richter’s profound performance. The two masters approach this work in entirely different ways—Horowitz maximizes the dramatic contrasts while Richter focuses on the inner narrative. Among contemporary performers, Daniil Trifonov’s delicate yet powerful interpretation is also noteworthy.

From Grieg’s night to Tchaikovsky’s night. These two composers worked in different cultural spheres, yet both explored the human interior with their own unique musical languages. If you play the Dumka for ears still carrying the resonance of the Notturno, you will experience the infinite spectrum that classical music contains.