📑 Table of Contents

Have you ever walked through a space that belonged to someone you loved—someone who’s no longer here? The way your footsteps feel heavier, how you pause at unexpected moments, moving between memories and the unbearable present?

That’s exactly what this piece captures. Not in metaphor, but in literal musical autobiography.

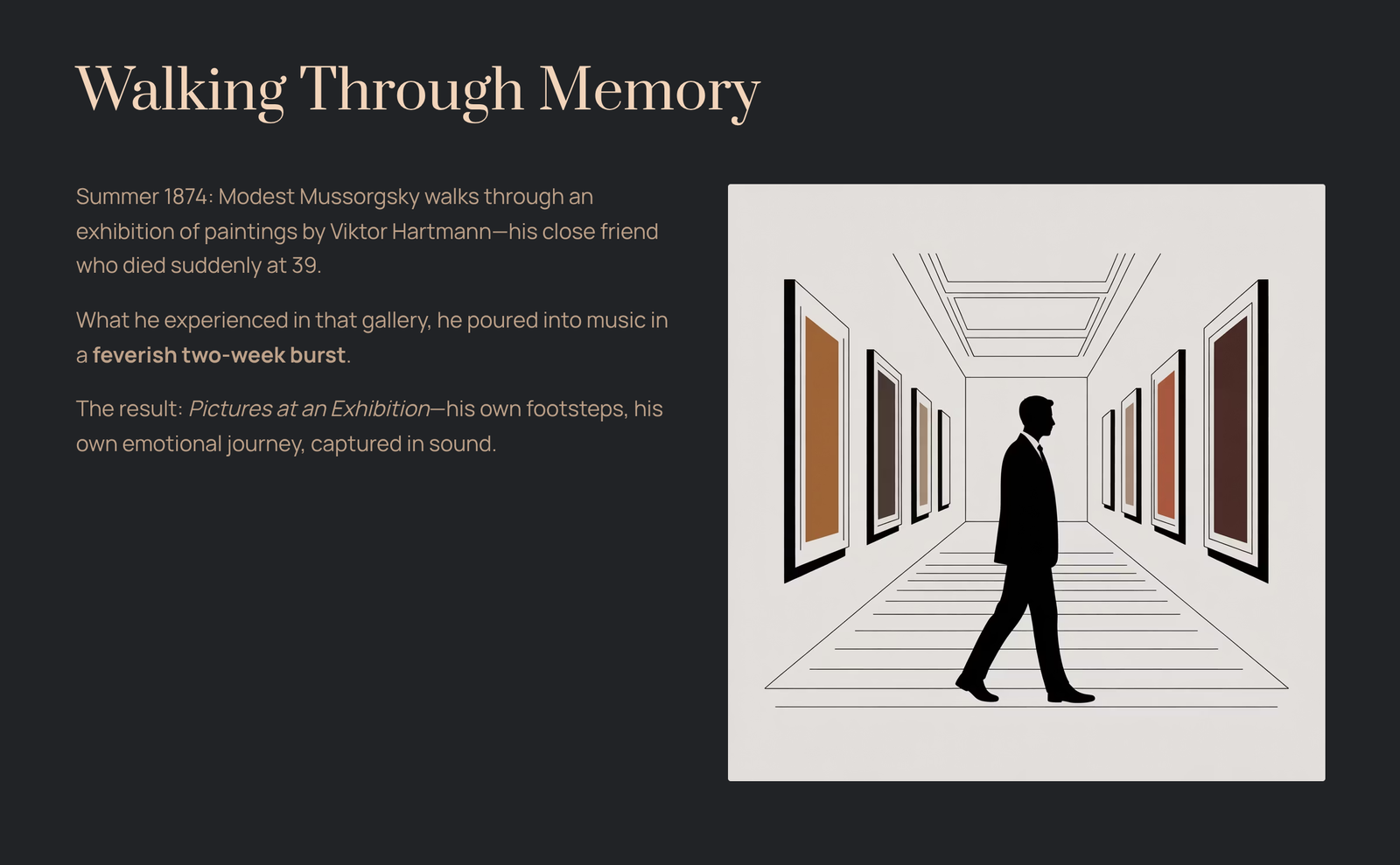

In the summer of 1874, Modest Mussorgsky—a burly Russian composer still riding high from the success of his opera Boris Godunov—walked through an art exhibition. The paintings belonged to Viktor Hartmann, his close friend who had died suddenly just months earlier at age 39. What Mussorgsky experienced in that gallery, he poured into music in a feverish two-week burst of composition.

The result was Pictures at an Exhibition, and its recurring theme—the Promenade—is nothing less than Mussorgsky’s own footsteps, his own emotional journey, captured in sound.

The Heartbreak Behind the Music

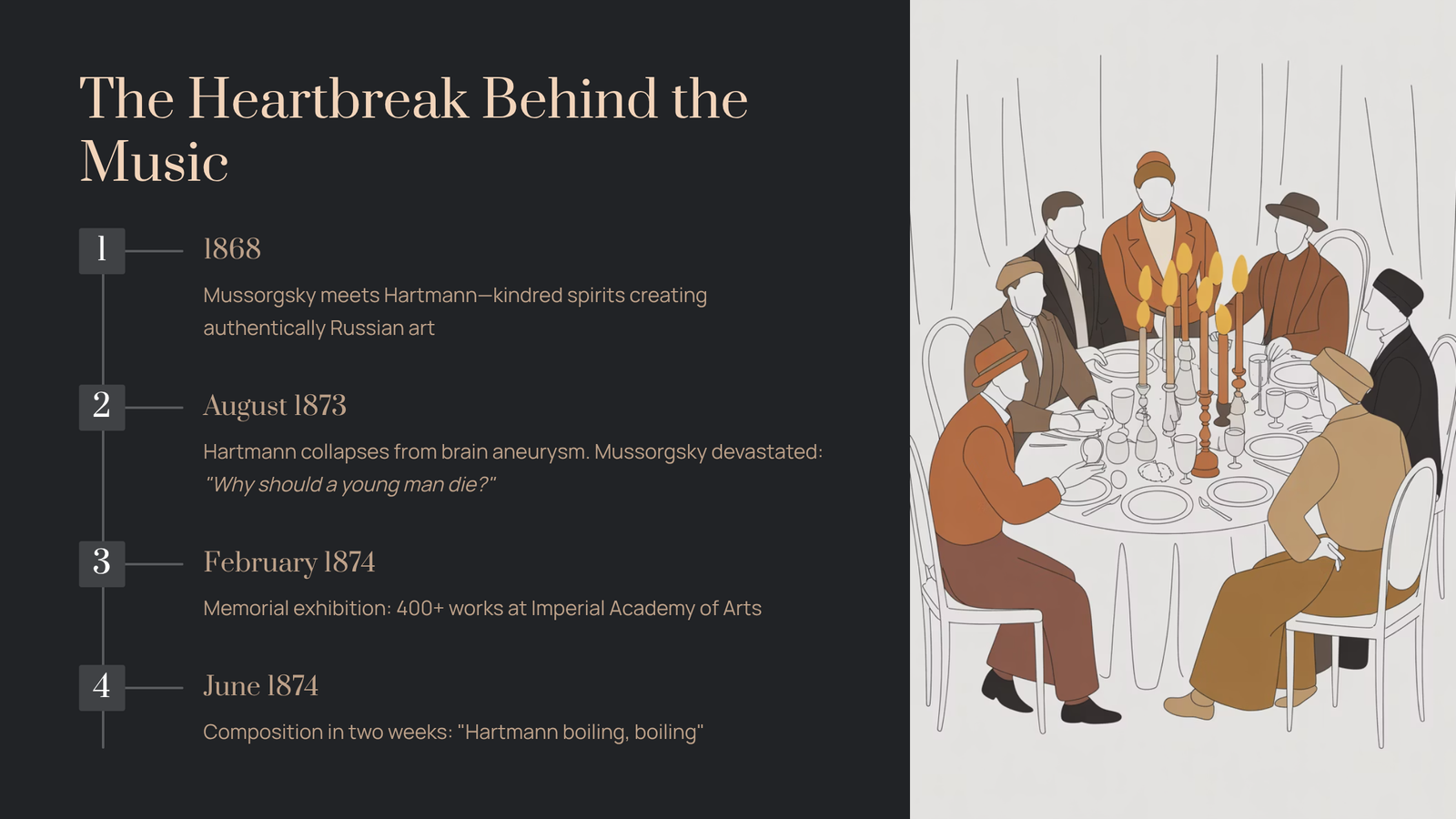

Viktor Hartmann wasn’t just any friend. He was a kindred spirit—a fellow artist who believed in creating authentically Russian art, free from Western European conventions. The two men had met around 1868 through Vladimir Stasov, a prominent music critic who would later receive the dedication of this very work.

When Hartmann collapsed from a brain aneurysm in August 1873, Mussorgsky was devastated. In a letter to Stasov, he wrote with raw anguish: “What a terrible blow! Why should a young man die?”

Six months later, Stasov organized a memorial exhibition at the Imperial Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg, displaying over 400 of Hartmann’s works. Mussorgsky attended—and the experience overwhelmed him.

He later described his state during composition as “Hartmann boiling, boiling like ‘Boris’ did, sounds and ideas floating in the air.” He could barely scratch the notes down fast enough. This wasn’t just music-making; it was grief finding its voice.

What Makes the Promenade So Unique

Here’s where things get interesting for anyone who loves understanding how music works.

The Promenade opens with an unusual time signature—alternating between 5/4 and 6/4 (or, in Mussorgsky’s original notation, a single 11/4 measure). This creates an asymmetrical, almost limping quality to the rhythm. Why would a composer choose something so unconventional?

There are two fascinating interpretations.

The first is physical: Mussorgsky was a large man, and some scholars suggest he was musically depicting his own heavy, shuffling gait as he moved through the gallery. There’s a touch of self-aware humor here—the composer acknowledging his own bulk.

The second interpretation is psychological: the uneven rhythm mirrors the emotional instability of grief. When you’re processing loss, nothing feels quite balanced. You move forward, then hesitate. You’re drawn toward something, then pull back. The 5+6 pattern captures this beautifully—always slightly off-kilter, never quite settling.

The melody itself is built on a pentatonic scale (think of the black keys on a piano), giving it a distinctly Russian folk quality. It sounds ancient, sturdy, honest. Mussorgsky deliberately avoided the sophisticated harmonic language of Western European classical music, choosing instead something that felt authentically his own.

A Guided Walk Through the Music

Let’s walk through the Promenade together. If you’re listening to Ravel’s famous orchestral version (more on that later), here’s what to notice:

The Opening (0:00–0:45)

A solo trumpet announces the theme—bold, clear, and declarative. This was Ravel’s inspired choice; the original piano version presents the melody as a single unaccompanied line. The trumpet’s bright, resonant tone suggests confidence, perhaps even the initial composure we try to maintain when entering an emotionally charged space.

Notice how the rhythm keeps shifting—five beats, then six. It’s like footsteps that can’t quite find a steady pace.

The Growing Ensemble (0:45–1:15)

Other brass instruments begin to join: French horns, trombones, tuba. The melody repeats, but now it’s harmonized, gaining weight and depth. This represents the growing emotional complexity of the experience—you’re no longer just observing the paintings; you’re beginning to feel their significance.

The Full Arrival (1:15–end)

Strings and woodwinds finally enter, creating what one critic called a “lush and lovely” sound. The theme has transformed from a solitary statement into a communal expression. It’s as if Mussorgsky is acknowledging that grief, while deeply personal, also connects us to something larger.

Throughout the full suite, the Promenade returns several times, but never the same way twice. After viewing the grotesque “Gnomus,” the Promenade becomes calm and somber. Later iterations grow heavier, slower, more contemplative. The music literally tracks how each artwork affects the listener’s emotional state.

The Tangled History of What We Actually Hear

Here’s a twist that music historians love to argue about.

Mussorgsky wrote Pictures at an Exhibition for solo piano, and it went unpublished during his lifetime. When it finally appeared in 1886—five years after his death—it had been “corrected” by his colleague Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. These corrections actually altered significant elements of Mussorgsky’s unconventional style, smoothing out the very rough edges that made his music distinctive.

The truly original score wasn’t published until 1931—57 years after composition.

Then there’s the orchestral version we know best, created by Maurice Ravel in 1922. Here’s the irony: when Ravel requested Mussorgsky’s original manuscript, a friend accidentally sent him the Rimsky-Korsakov edition instead. So the world’s most famous orchestration is actually based on an “improved” version, not the raw original.

Does this matter? Some purists say yes—we’re hearing a filtered version of Mussorgsky’s vision. Others argue that Ravel’s genius for orchestral color elevated the work into something even more powerful. The debate continues.

Recommended Recordings to Start Your Journey

For the Piano Original:

Sviatoslav Richter’s legendary 1958 live recording captures the raw, almost violent emotional intensity Mussorgsky intended. His fortissimo opening was so aggressive it initially shocked audiences accustomed to more polished interpretations. Today, it’s considered one of the greatest piano recordings ever made.

For the Orchestral Experience:

The Ravel orchestration conducted by virtually any major orchestra will give you the full cinematic experience. Look for recordings by the Chicago Symphony or Berlin Philharmonic for particularly stunning brass work in the Promenade.

For Something Different:

Emerson, Lake & Palmer’s 1971 progressive rock version brings synthesizers and electric guitar to Mussorgsky’s themes—proof that this 150-year-old music still speaks to contemporary ears.

Why This Music Still Matters

Four hundred of Hartmann’s artworks were displayed at that 1874 exhibition. Today, only about six can be identified. The paintings that inspired Mussorgsky have largely disappeared into history.

But the music remains.

There’s something profound in this reversal. Hartmann was a visual artist; his work was meant to be seen. Yet it’s Mussorgsky’s sonic memorial that has preserved his friend’s memory for generations. Every time an orchestra performs the Promenade, every time a pianist strikes those opening notes, Viktor Hartmann lives again.

And perhaps that’s the deepest truth this music teaches us. Grief doesn’t just weigh us down—it can also drive us to create something that transcends our own mortality. Mussorgsky walked through an exhibition of his dead friend’s art and emerged with a work that would outlast them both.

The next time you hear those uneven footsteps—five beats, then six—remember: you’re walking alongside a grieving composer, through a gallery of lost paintings, into a kind of immortality.