Table of Contents

Soul Fragments Salvaged from Three Days of Hell

Some music strikes your chest and passes through in an instant. But the second movement of Dmitri Shostakovich’s String Quartet No. 8 in C minor, Op. 110 is different. This music doesn’t strike and pass—it embeds itself in our souls and continues pulsating. Like the relentless hammering of metal, like an alarm sounding from deep within our chest.

July 12-14, 1960. Just three days. Walking through the desolate streets of ruined Dresden, what Shostakovich extracted from his inner depths was the most harrowing and beautiful confession in musical history. Shortly after being forced to join the Soviet Party, he carved his own name into musical notes, preparing to bid farewell to this world.

The second movement Allegro molto represents the pinnacle of that despair. In just 2 minutes and 40 seconds, all the terror and personal anguish of the 20th century is compressed. Have you ever felt it too? That moment when something inside wants to explode, but you know no one will understand that loneliness?

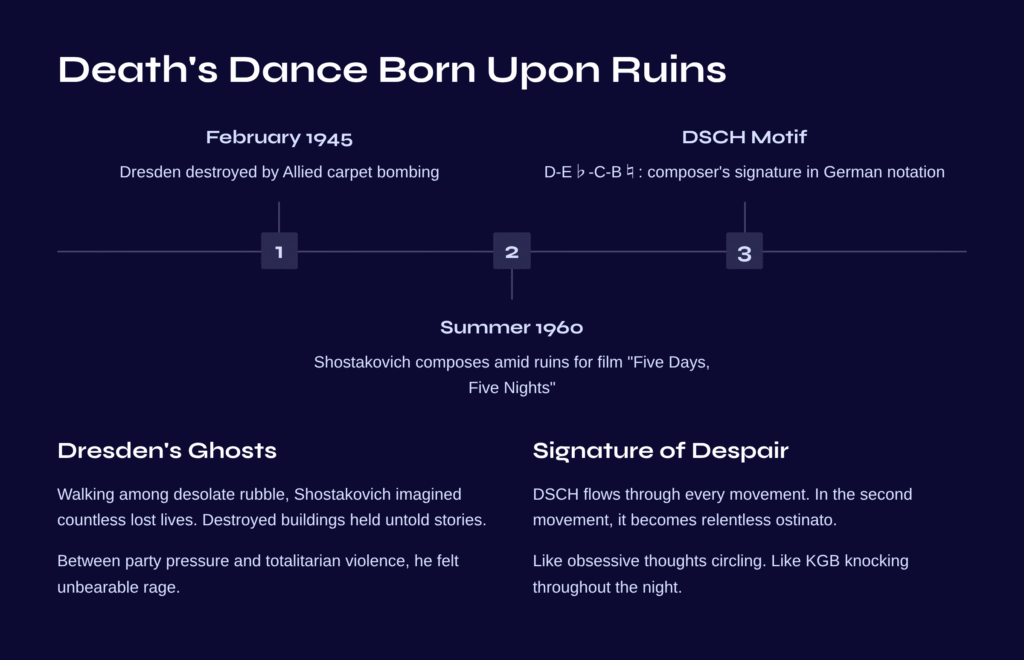

Death’s Dance Born Upon Ruins

The Story the Ghosts of Dresden Whispered

February 1945: Dresden was completely destroyed by Allied carpet bombing. Fifteen years later, in the summer of 1960, Shostakovich was staying amid those ruins, composing music for a film called “Five Days, Five Nights.” The film’s backdrop was precisely that 1945 catastrophe.

Walking among the desolate rubble, what did Shostakovich see? Did he imagine the traces of countless lives that had been here fifteen years ago, the stories that the destroyed buildings had held? And between the reality of having just succumbed to party pressure and the totalitarian violence symbolized by these ruins, did he feel unbearable rage?

DSCH – A Signature of Despair Written in His Own Name

Throughout all movements of this String Quartet No. 8, one obsessive motif flows: DSCH. Shostakovich’s own name written in German musical notation: D-E♭-C-B♮. These four notes become the composer’s signature, like Bach’s B-A-C-H, flowing through every movement.

But in the second movement, this DSCH motif transcends mere signature. It becomes a relentless ostinato that penetrates our consciousness. Like obsessive thoughts circling in our heads, like the sound of KGB knocking heard throughout the night.

Listen to the second movement for the first time. Notice this violent explosion that suddenly erupts from the first movement’s meditative sadness. It is rage arriving without warning—the raw moment when emotions long suppressed can no longer be contained.

The Rhythm of Invisible Whips

Human Cries Hidden in Mechanical Repetition

Examining the structure of the second movement reveals a chilling beauty. It doesn’t follow traditional sonata form but instead adopts a “loose fugato” structure. What the four string instruments create by passing the DSCH motif among themselves is not dialogue but collective compulsion.

After the violent explosion of the first fifteen seconds, violin and cello begin endlessly repeating DSCH in dotted rhythm. This repetition evokes what musicologists call “terrifying” emotions. Why terrifying? Because it is simultaneously mechanical and desperately human.

One performer described this passage as “a hamster trapped on a wheel, repeating meaningless actions.” Endless repetition, circulation without exit. How closely this resembles the life of Shostakovich, who had to live as an artist under the Soviet system.

The Jewish Dance in the Middle Section – Exposing History’s Wounds

About a minute in, a new voice invades the music: the Jewish theme. This is a Klezmer-influenced dance melody that Shostakovich had used in his earlier Piano Trio No. 2.

The moment this theme suddenly appears in the second movement, the music expands beyond personal despair to historical tragedy. It becomes silent testimony to the Holocaust, genocide, and all forms of racial violence. Shostakovich opposed anti-Semitism and carefully expressed his position through this musical allusion.

One critic described this passage: “While the cello sings an aria in its husky register, the violin sounds like insects crawling under its skin. Like the rat cage in Orwell’s 1984.” A description both chilling and precise.

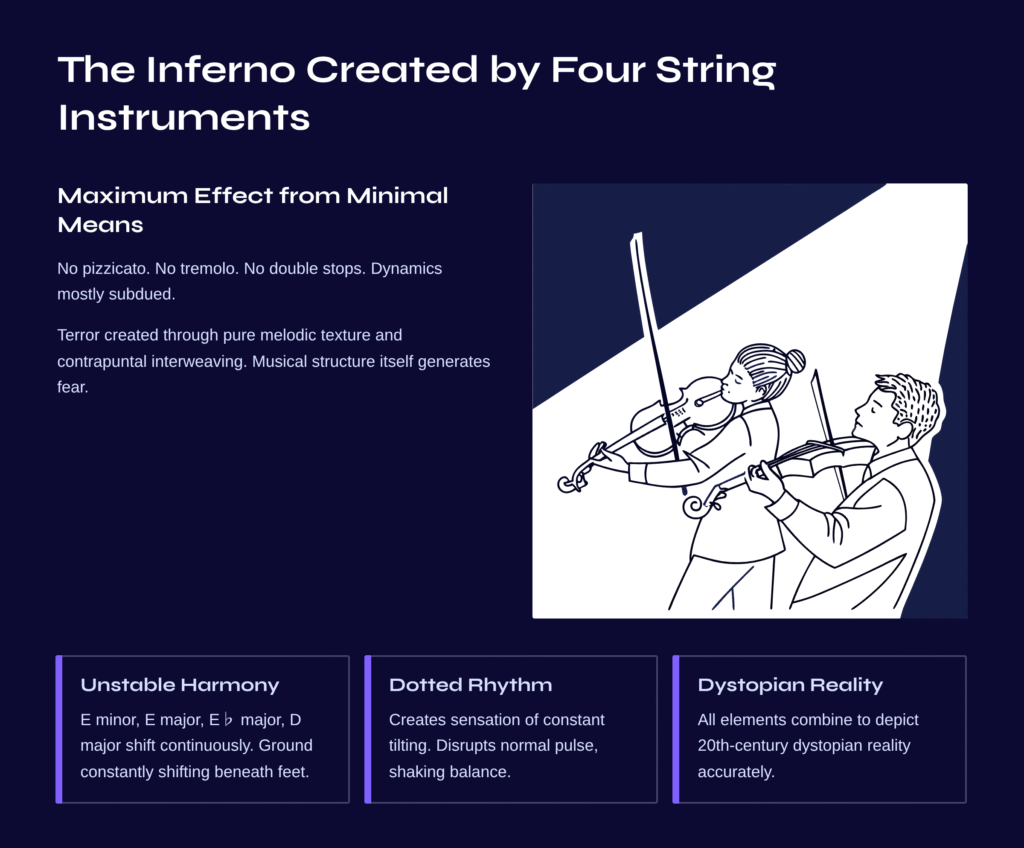

The Inferno Created by Four String Instruments

Maximum Effect from Minimal Means

Remarkably, this second movement uses almost none of the flashy techniques available to string quartet. No pizzicato, no tremolo, no double stops. The dynamics remain mostly subdued, with only one forte appearing.

Yet why does this music leave such an intense impression? Because it relies solely on pure melodic texture and contrapuntal interweaving. Instead of flashy techniques, Shostakovich created terror through the very structure of the music.

The harmony is extremely unstable. E minor, E major, E♭ major, and D major shift continuously while maintaining the B natural. This expresses musical instability and chaotic disorder. Like ground constantly shifting beneath our feet, we cannot find stability.

The Tilted World Created by Dotted Rhythm

The rhythmic characteristic of this movement lies in its dotted rhythm. This pattern destabilizes the melody, creating a sensation of constant tilting. It disrupts normal pulse, shaking even our sense of balance.

Ultimately, all these elements combine—DSCH’s obsessive repetition, the sudden invasion of the Jewish theme, unstable harmony, tilted rhythm—to create an accurate musical depiction of 20th-century dystopian reality.

A Map of Despair for the Heart

First Listening: Accepting the Shock

When first hearing this second movement, don’t try to analyze. Simply accept the shock as it comes. Feel with your whole body the violent energy suddenly erupting from the first movement’s meditative sadness, and its gradual transformation into mechanical repetition.

This music doesn’t try to be beautiful. Instead, it strives to be truthful. It seeks to convey directly to us the authenticity of the despair and rage Shostakovich felt.

Second Listening: Tracing DSCH’s Path

On your second listen, pay careful attention to how the DSCH motif transforms and repeats. Track the process by which these four notes—D-E♭-C-B♮—are transformed into dotted rhythm and come to dominate the entire movement.

Particularly after the 1:30 mark, this motif appears in more intense and concentrated form. The intensity increases as if spiraling downward. Finally, it gradually fades while leading to the silence of the next movement.

Third Listening: Absorbing the Jewish Theme’s Meaning

On your third listen, focus on the Jewish theme appearing in the middle section. Keep in mind that this is not merely melodic contrast but historical testimony.

The moment this theme appears, the music transcends Shostakovich’s personal despair to encompass the entire tragedy of the 20th century. It becomes secret testimony to Holocaust memory, genocide terror, and all forms of racial violence.

Various Colors of Despair from Different Performers

Borodin Quartet – The Only Interpretation the Composer Approved

The Borodin Quartet’s 1962 recording and 1991 re-recording remain the most authoritative interpretations of this work. When the Borodin Quartet performed this piece at Shostakovich’s home in 1962, the composer reportedly wept and bowed his head. When the performance ended, they quietly packed their instruments and left.

In the Borodin Quartet’s interpretation, you can feel that this music transcends mere political protest to become a meditation on the tragic condition of human existence itself.

Emerson String Quartet – Sophisticated Technical Control

The Emerson String Quartet’s recording is famous for its “extremely sophisticated technical control and subtle expression.” In their performance, the structural intricacy of the second movement emerges more clearly. Without being swept away by emotion, they present the music’s logical necessity perfectly.

St. Lawrence String Quartet – Dance of Death

The St. Lawrence String Quartet’s 2006 recording is praised as a “more passionate and emotionally engaging” interpretation. Musicologists described their performance as “delivering the movement almost like a Danse Macabre.”

In their interpretation, the dance-like character of death and despair in the second movement becomes more pronounced. It sounds like a contemporary reinterpretation of a medieval dance of death.

The Universality of Despair Transcending Time

This music that Shostakovich poured out in three days amid Dresden’s ruins still strikes our hearts 65 years later. Why?

Because what this music contains is not just the despair of a 1960 Soviet artist. It holds the rage and despair of people in every era and place who have had their freedom suppressed and been unable to speak truth. And because our individual hidden angers—those we want to explode but cannot—find vicarious release through this music.

Like Shostakovich, who carved his name with four notes—DSCH—we each live our lives leaving our own signatures on this world in our own ways. Even when that signature is stained with despair and rage, it remains proof that we are alive.

Listening to this second movement, we come to realize that true art doesn’t pursue beauty alone. Sometimes revealing ugly truth is art’s most noble mission. And works created while bearing the weight of such truth are what reach human hearts across time.

Next Destination: The Quiet World Painted by Debussy’s “Footsteps in the Snow”

Having fully experienced Shostakovich’s violent despair and rage, it’s time to journey to a completely different dimension of musical world. Claude Debussy’s prelude “Des pas sur la neige” (Footsteps in the Snow) stands at the opposite pole from Shostakovich’s passion.

“Footsteps in the Snow” is the sixth piece from Debussy’s Préludes, Book 1, composed in 1910, an amazing poetic journey unfolding in about 3-4 minutes. While Shostakovich’s music rawly exposes historical violence and personal despair, Debussy’s work captures the most delicate tremors of the human interior within winter landscape’s silence.

Beginning with the instruction “Triste et lent” (Sad and slow), this piece musically depicts the footsteps of someone walking alone across snow-covered fields and the lonely traces those footprints leave. Where Shostakovich’s obsessive repetition was a prison of despair, Debussy’s repeating bass line creates a space of solitary but peaceful meditation.

A journey from emotional storms into quiet inner landscapes. Through the poetic beauty created by Debussy’s impressionistic colors and delicate harmonies, experience another healing power that music possesses.