Table of Contents

In That Moment, Time Seemed to Stand Still

As the harp’s first arpeggio rippled through the air, I found myself drifting to places unknown. When the flute began its quiet sustained note and the strings emerged like mist taking shape into melody, something stirred in the depths of memory. Not a memory I had lived, nor a story I had heard, but perhaps something that sleeps in all our hearts—a feeling as old as longing itself.

Vaughan Williams’ “Fantasia on Greensleeves” is such music. Within a mere five minutes, it holds four centuries of time, carrying a song once sung in 16th-century English taverns to us in the 21st century with the grace of magic. Have you ever felt this while listening—the moment when time’s boundaries blur, when past and present meet within a single melody?

From Folk Song to Masterpiece – The Extraordinary Journey of Greensleeves

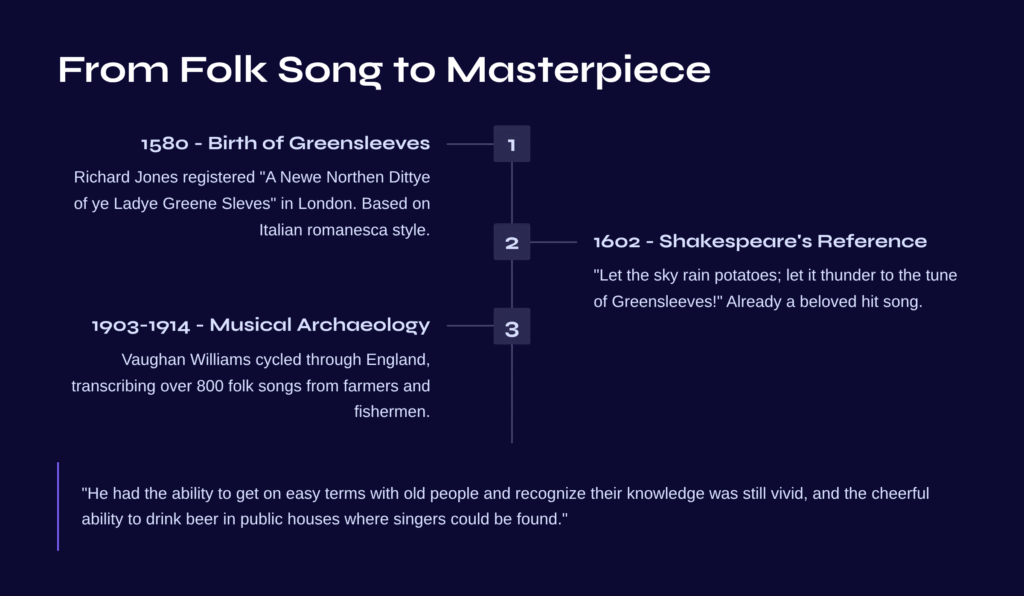

A Journey to the 16th Century

The name “Greensleeves” conjures that haunting melody we’ve all encountered at some point. The song’s documented history begins in 1580, when Richard Jones registered “A Newe Northen Dittye of ye Ladye Greene Sleves” in London. Though romantic legend credits Henry VIII with composing it for Anne Boleyn, scholars believe it was actually created during the Elizabethan era, based on the Italian romanesca style that arrived in England after Henry’s time.

Shakespeare, too, must have loved this tune. In 1602’s “The Merry Wives of Windsor,” he wrote, “Let the sky rain potatoes; let it thunder to the tune of Greensleeves!” It was already a hit song that everyone knew by heart.

The Passionate Folk Collector

Vaughan Williams was more than just a composer—he was a musical archaeologist. From 1903 to 1914, he cycled throughout England, personally transcribing over 800 folk songs. In the East Anglia region, he would share a pint with farmers and fishermen, recording the songs that had passed from voice to voice across generations.

His wife Ursula testified to his unique gift: “He had the ability to get on easy terms with old people and to recognize that their knowledge of and pleasure in their songs was still vivid, and the cheerful ability to drink beer in the public houses where many of the singers could still be found.” It was this marriage of musical passion and human warmth that birthed these timeless works.

The Sound Magician’s Five-Minute Epic

Mysterious Beginnings – The Door to Time Opens

The piece opens with a harp’s F major arpeggio, like ancient cathedral bells echoing through time. Through these resonant chords, a flute sustains a long F, creating what feels like an enchanted circle. These five bars of introduction serve as a bridge between reality and fantasy, past and present, drawing us into 16th-century England.

The F Dorian mode employed here creates colors unlike our familiar major or minor scales—neither bright nor dark, but inhabiting that melancholy-beautiful middle ground perfect for expressing emotions that exist between joy and sorrow.

The Entrance of Greensleeves – A 400-Year-Old Lover’s Lament

When the second violins and violas carefully begin that famous melody, something tightens in the chest. Rising above the harp’s lute-like accompaniment and the strings’ tremolo, this melody feels like an ancient lover’s lament drifting from the mist-covered English countryside.

“Greensleeves was all my joy, Greensleeves was my delight…” The song of a 16th-century man mourning his departed lover in her green-sleeved dress has been transformed by Vaughan Williams’ hand into something eternal.

Lovely Joan’s Playful Interlude – A Change of Mood

The middle section brings a complete transformation. “Lovely Joan,” a Norfolk folk song, dances playfully through two flutes. This tells the witty tale of a young man attempting to seduce a maiden named Joan, only to have her outsmart him, steal his horse and ring, and escape.

The two flutes’ teasing exchange sounds like lovers’ banter or children laughing in spring meadows. Here, the music briefly escapes from melancholy into the vibrant life of common people.

Greensleeves Returns – With Deeper Feeling

After Joan’s lightness passes, Greensleeves returns, but now carried by the warmer, richer voices of viola and cello. This time, the emotion has matured far beyond the first appearance—like love that has weathered time’s weight and emerged deeper.

Finally, the violins carry the closing strain. The journey from initial mystery through middle vitality to final acceptance creates a mature beauty that mirrors life itself.

My Own Journey Through Time’s Emotion

Each time I hear this piece, I’m swept by inexplicable feeling. The yearning of someone 400 years ago, singing for their departed love in an English tavern, reaches me as vividly as my own memories. Along with it comes the excitement and tenderness Vaughan Williams must have felt cycling through English villages in the early 1900s.

Especially when the violins play that final melody, I always feel a strange peace. Not resignation, but acceptance—the comfort that though all things pass, beauty endures forever.

Perhaps this is the greatest gift this music offers: awakening those universal emotions sleeping in each of our hearts—memories of love, the pain of parting, time’s impermanence, and the beauty of life that embraces it all.

Three Keys to Deeper Listening

1. Listen to the Instrumental Conversation

The true magic lies in how each instrument’s voice harmonizes with the others. Notice consciously how the harp’s antique arpeggios, flute’s pastoral melodies, and strings’ warm chorus blend together. It’s as if musicians from different centuries have transcended time to perform together.

2. Track the Melody’s Transformations

Follow how Greensleeves first appears in second violin, transforms into Lovely Joan, then returns in viola and cello. Though the same melody, each instrumental voice brings completely different emotions. This is the magic of arrangement.

3. Start with Marriner or Barbirolli

Different conductors and orchestras bring vastly different interpretations. Neville Marriner’s Academy of St Martin-in-the-Fields offers delicate, elegant interpretation, while John Barbirolli provides more emotional, dramatic approach. Comparing these versions reveals the music’s many-faceted beauty.

Music’s Eternal Consolation

Whenever I hear Vaughan Williams’ Fantasia on Greensleeves, I reflect on music’s greatest gift: its power to transcend time. A love story from 400 years ago can still move our hearts today; an English country folk song can unite people across the globe.

Compressed within these five minutes are all human emotions—love’s joy and parting’s sorrow, youth’s exuberance and maturity’s depth, and life’s generosity that embraces everything. This music proves that the 16th-century heart yearning for a departed lover beats no differently than our own hearts today.

As beautiful music always does, it asks us: What is your Greensleeves? What do you long for and wish to sing of eternally? Like the timeless beauty Vaughan Williams discovered in a 16th-century folk song, each of our lives contains precious moments worthy of transcending time. To discover, remember, and love these moments—perhaps this is the greatest gift this music offers us.

An Invitation to the Next Journey – Mahler’s Hope in Darkness

If you’ve been thoroughly enchanted by Greensleeves’ lyrical beauty, why not venture into an entirely different emotional realm? Gustav Mahler’s “Songs on the Death of Children,” specifically the first song “Now the sun wants to rise so brightly,” addresses humanity’s deepest grief while finding light within that darkness.

From 16th-century English pastoral love song to late 19th-century Austrian existential depth. From Vaughan Williams’ warm comfort to Mahler’s philosophical contemplation. Hearing these two works in sequence reveals the incredible breadth and depth of emotion that classical music can contain—how the language of music transcends time, space, and linguistic barriers to reach our deepest selves.