Table of Contents

A Letter of Mourning Written in Sound

Some music finds a quiet place in your chest the moment you hear it. When emotions beyond words flow from the low strings of a cello, we finally understand: grief, too, can be this beautiful. Gabriel Fauré’s Élégie, Op. 24, is that kind of music.

This piece reaches you more deeply not under the bright lights of a concert hall, but rather in the quiet of a late evening, when you’re sitting alone. When the sun sets outside your window and darkness slowly descends into the room. When the cello’s first note sounds, we listen as people who have lost someone, or lost something, leaning into that sound with recognition.

Fauré contained everything within this brief work. Mourning and remembrance, resignation and comfort. And beyond all these emotions, salvation in the form of beauty itself.

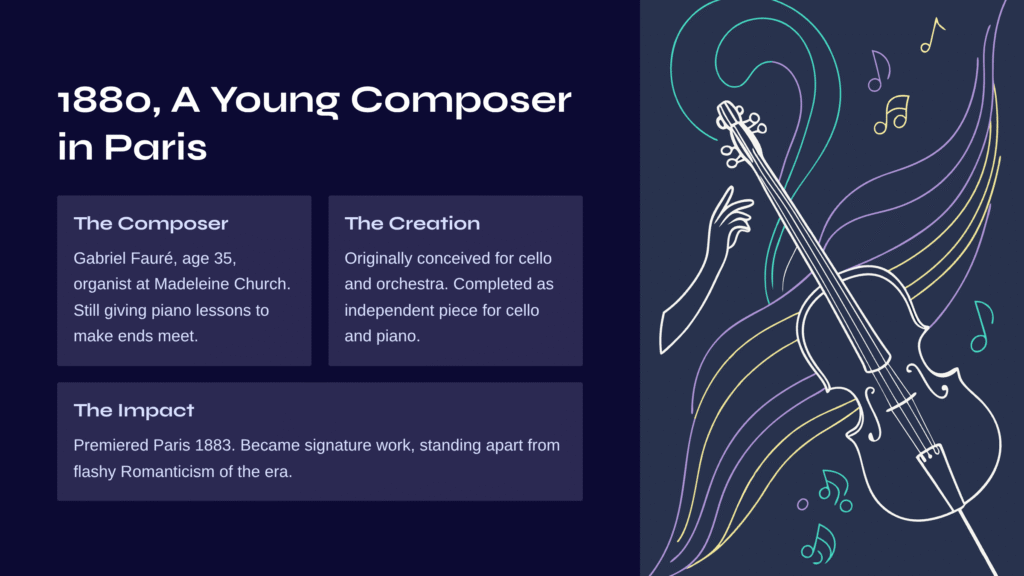

1880, A Young Composer in Paris

Gabriel Fauré completed the Élégie in 1880, when he was 35 years old. At the time, Fauré was gradually gaining recognition as the organist at the Madeleine Church and as a composer. But he still needed to give piano lessons to make ends meet, and time to devote to composition was always scarce.

The Élégie was originally conceived as part of a larger work for cello and orchestra, but was ultimately completed as an independent piece for cello and piano. After its premiere in Paris in 1883, it quickly became one of Fauré’s signature works. What’s remarkable is that this piece stood apart from the flashy Romanticism and dramatic expression that dominated French music at the time.

Fauré’s musical language is restrained yet profound. He doesn’t shout. Instead, he touches the deepest parts of our hearts quietly but surely. The Élégie is where Fauré’s musical identity appears in its purest form.

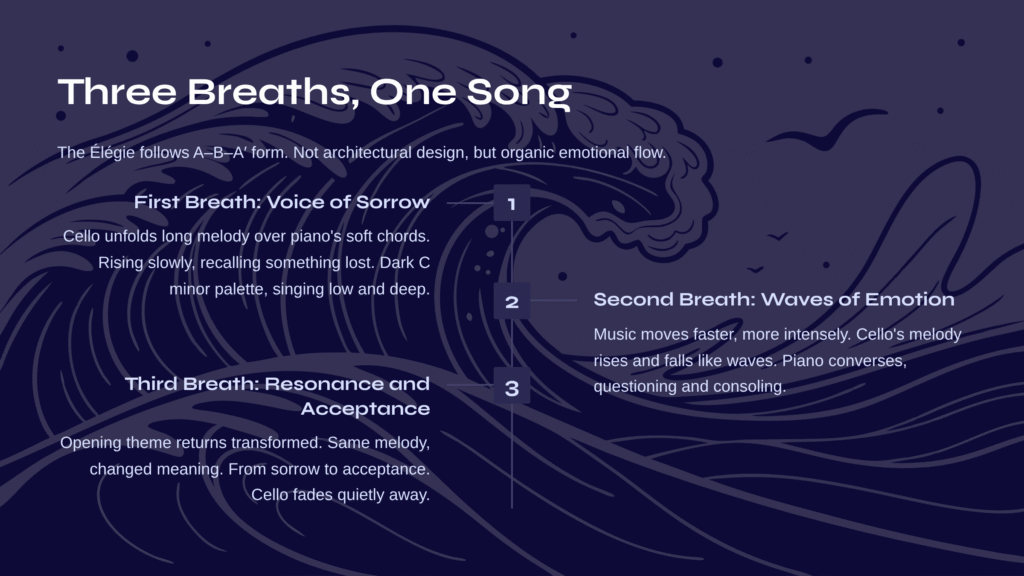

Three Breaths, One Song

The Élégie consists of just one movement, but within it lies a clear three-part structure. An A–B–A′ form—a theme presented, transformed, and returned. Yet this isn’t an architectural design for textbook formal beauty. Rather, it feels like a structure that emerged naturally by following the organic flow of emotion.

The First Breath: A Voice of Sorrow

The piece begins with the cello unfolding a long melody over the piano’s soft chords. This melody rises slowly, carefully into the air, as if recalling something lost long ago. Within the dark palette of C minor, the cello doesn’t cry out. Instead, it sings low, deep, with a sound that resonates from the depths of the chest.

When listening to this section, I recommend paying attention to the cellist’s breathing. The beginning and end of phrases, how the cello breathes in between. Like a person speaking, the cello also breathes as it sings. Between those breaths, Fauré’s harmonies shift subtly, and the piano follows the cello like a shadow.

The Second Breath: Waves of Emotion

In the middle section, the music moves a bit faster, a bit more intensely. But even “intense” is relative for Fauré. He still speaks in restrained language. Only the amplitude of emotion grows larger within it.

This section, where the cello’s melody rises and falls, rises again, feels like waves rolling in and receding. Or like emotional currents stirring in someone’s chest. The piano is no longer mere background. It converses with the cello, sometimes questioning, sometimes consoling.

In this moment, the music doesn’t remain in the single emotion of sorrow. Anger, resignation, longing, hope—all are mixed in. Human emotions are like that, after all. Not simple, intricately intertwined, sometimes even contradictory.

The Third Breath: Resonance and Acceptance

When the opening theme returns in the recapitulation, we realize: this is not simple repetition. The same melody, but its meaning has changed. What was first a voice of sorrow is now the voice after accepting that sorrow. Should we call it resignation, or perhaps peace?

The cello no longer resists. Quietly, softly, it sings the final melody and fades away. When the piano’s last chord disperses into the air, we finally understand what this music tried to tell us.

What I Found in This Music

When I first heard the Élégie, I didn’t cry. Instead, I sat very still for a long time. Even after the music ended, its resonance seemed to linger in the room. As if someone had just been there moments before.

This piece doesn’t deliver a grand message. It doesn’t say “overcome your grief” or “have hope.” Instead, it seems to say: “It’s okay to be sad. That sadness is part of you. And even that can be beautiful.”

Listening to this music, I thought: perhaps the greatest gift art can give us is comfort. Not solutions, but presence. Telling us we’re not alone. Fauré’s Élégie is that kind of music.

Three Keys to Deeper Listening

1. Compare Multiple Performances

The Élégie has been performed by countless cellists. Pablo Casals and Alfred Cortot’s 1934 recording holds great historical value—a performance marked by natural breathing and rich phrasing. Mstislav Rostropovich and Sviatoslav Richter’s 1960 recording is more dramatic and intense. Jacqueline du Pré and Daniel Barenboim’s 1967 recording is overwhelming in its emotional amplitude and lyricism.

Yo-Yo Ma and Kathryn Stott’s 1984 recording presents a modern, balanced interpretation, while Steven Isserlis and Stephen Hough’s 1998 recording features refined, transparent sonority. That the same piece can speak in such different voices—this is the charm of classical music.

2. Focus on the Cello’s Breathing

The cello is said to be the instrument closest to the human voice. When listening to the Élégie, pay attention to where the cello breathes, where it begins and ends phrases. As if someone is telling you a story, follow the rises and falls, the changes in pace of that voice. You’ll discover interpretations unique to each performer that aren’t written in the score.

3. Listen Repeatedly

The Élégie is a short piece—about six to seven minutes. But it’s difficult to discover everything contained within that brief time in one hearing. The first time, follow the overall atmosphere; the second, the cello’s melody; the third, the piano’s harmonies. Each listening will reveal something new. Good music is layered like that.

Beauty Beyond Sorrow

Fauré’s Élégie is music of mourning. But it is not music of despair. Quite the opposite. This piece tells us: grief is part of life, and it can be transformed into music. Beauty comes not only from joy but also from sorrow.

Listening to this music, I think about how we should accept loss when we lose someone, when we lose something. Fauré doesn’t give answers. Instead, he sits beside us, quietly playing his cello, saying: “I know. I’ve been there too.”

And that’s enough. Sometimes presence matters more than solutions, a single piece of music more than words of comfort.

After the music ends, after the last note dissolves into air, we still remain in that resonance. And we quietly realize: sorrow, too, can become song. And that song makes us a little more human.

The Next Journey: Vaughan Williams’s Fantasia on “Greensleeves”

If Fauré’s delicate mourning has quietly seeped into your heart, it’s time to encounter a different kind of longing. Ralph Vaughan Williams’s Fantasia on “Greensleeves” is a work that unfolds an ancient English folk tune through orchestra.

Where Fauré sang of personal grief, Vaughan Williams sings of collective memory carried across time. Pastoral yet poignant, this music evokes walking through misty English countryside roads, stirring our nostalgia in a way distinct from the Élégie.

When the melody of the 16th-century English folk song “Greensleeves” flows over the soft tones of string orchestra and harp, we find ourselves longing for a place we’ve never been. Like a landscape once seen in a dream. This piece contains not personal loss but nostalgia for vanished times and places.

From the intimacy of chamber music to the richness of orchestra, from French elegance to English simplicity. If you listen to these two pieces in succession, you’ll encounter many faces of sorrow. And you’ll discover that all those faces can be beautiful.