Table of Contents

That Moment When Time Seemed to Stand Still

Sometimes music gifts us with the suspension of time itself. That moment when I first heard the fourth movement of Mahler’s Symphony No. 9 was exactly that. From the very first measures when the strings began their quiet resonance, it felt as though all the sounds of the world had vanished, leaving only this melody behind. It wasn’t simple beauty. It was something much deeper, much more poignant.

This music sings of farewell. But at first, I couldn’t grasp how complex and multilayered the meaning of that farewell truly was. I could only feel something resonating from deep within my heart. Like fragments of long-forgotten memories suddenly surfacing.

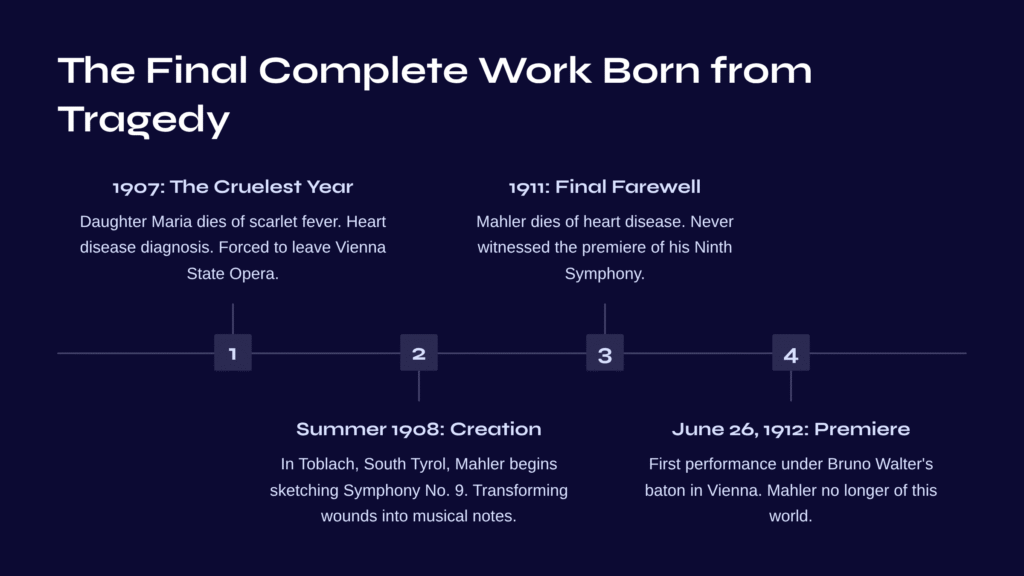

The Final Complete Work Born from Tragedy

For Gustav Mahler (1860-1911), 1907 was the cruelest year of his life. His four-year-old daughter Maria died of scarlet fever, he received a diagnosis of heart disease, and he was forced to leave the Vienna State Opera where he had devoted so many years. These three successive blows plunged Mahler into the depths of despair.

Yet paradoxically, from this extreme suffering emerged his most sublime work. In the summer of 1908, in Toblach, South Tyrol, Mahler began sketching his Symphony No. 9. As if transforming his wounds into musical notes, he poured everything into this composition.

This symphony was the last one Mahler completed during his lifetime. He died of heart disease in 1911 and never witnessed the premiere of his Ninth Symphony. When it was first performed on June 26, 1912, under Bruno Walter’s baton in Vienna, Mahler was no longer of this world.

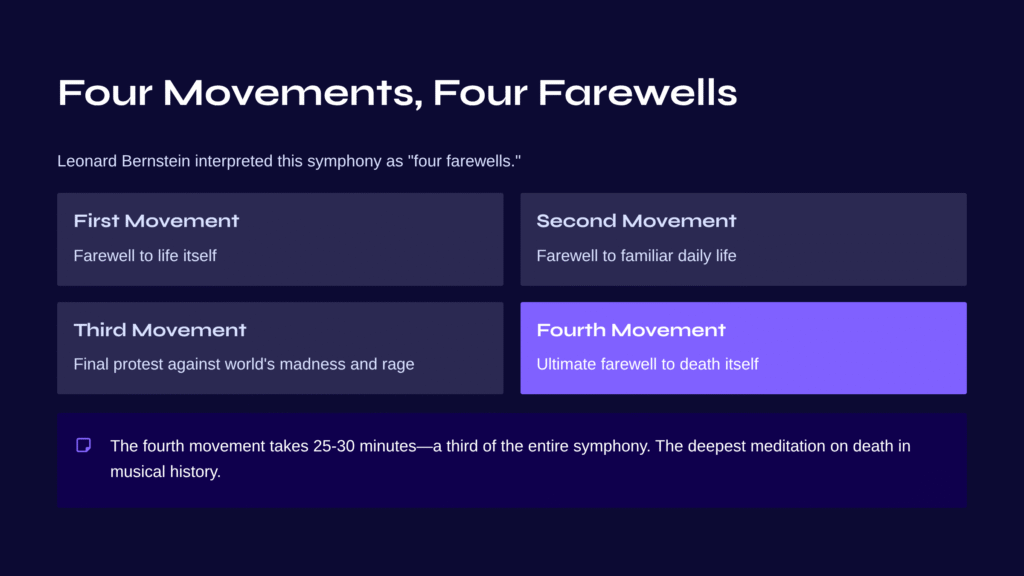

Four Movements, Four Farewells

Conductor Leonard Bernstein interpreted this symphony as “four farewells.” In the first movement, a first farewell to life itself; in the second movement, farewell to familiar daily life; in the third movement, a final protest against the world’s madness and rage; and in the fourth movement, the ultimate farewell to death itself.

The fourth movement, in particular, takes 25-30 minutes—a third of the entire symphony—to depict not merely death, but the process of reconciliation with death. This can be called the deepest meditation on death in musical history.

A Landscape of Farewell Painted in Sound

A Journey Beginning with Prayer

The fourth movement opens with quiet harmonies from the strings alone. It feels reverent, like stepping into a church or entering a sacred space. This theme bears similarity to the Christian hymn “Abide With Me,” which is likely no coincidence.

The music begins in an incomplete state. As if to say “there are still things left unsaid,” the melody sounds somehow incomplete and unfinished. This must have been Mahler’s intended effect. After all, life always ends in an unfinished state.

“Lebewohl” – The Theme of Eternal Farewell

Soon emerges the “Lebewohl (farewell)” theme. The descending whole-step repetition of F-E♭-D♭ is a musical translation of the German phrase “Lebe wohl (farewell).” As this melody permeates the entire music, the emotion of farewell deepens progressively.

But this farewell is not despairing. Rather, it feels like a process of acceptance. Like the quiet resignation that comes when finally facing reality that has long been avoided.

Tragic Fanfare – The Final Protest

In the middle section, a “tragic fanfare” filled with dissonance suddenly erupts. This ascending motif of C-C♭-B♭ sounds like a final protest: “Why must we die?” Here the music becomes momentarily violent, with anger and despair exploding in a mixture of emotions.

But this protest doesn’t last long either. It gradually subsides, returning to an atmosphere of resignation and acceptance. Like the deep fatigue that follows anger.

A Memorial to the Daughter in Memory

The most heart-wrenching moment comes when Mahler quotes a melody from his own song cycle “Kindertotenlieder (Songs on the Death of Children).” The melody of “The day is fine on yonder heights,” quietly played by the first violin, contains a father’s longing for his departed daughter Maria.

At this moment, the music transcends the dimension of personal tragedy. The pain of loss that all parents might experience, the sorrow of all who have lost loved ones, is condensed within this melody. It has the power to make listeners recall their own losses.

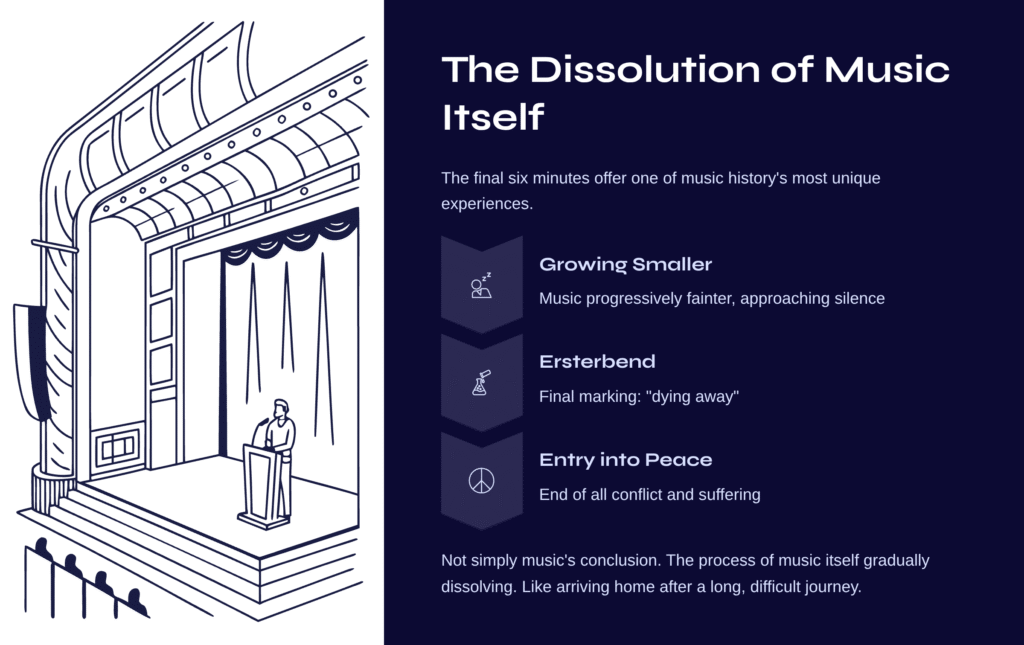

The Dissolution of Music Itself

The final six minutes of the fourth movement offer one of the most unique experiences in musical history. The music grows progressively smaller, fainter, finally reaching a state nearly approaching silence. The final marking is “ersterbend (dying away).”

This is not simply the conclusion of music. It is the process of music itself gradually dissolving. A few string sounds, a solitary high violin left alone, the faint resonance of the final horn… all of this depicts the process of life quietly extinguishing.

Yet this dissolution is not despairing. Rather, it feels like an entry into peace, the end of all conflict and suffering. Like the relief of finally arriving home after a long, difficult journey.

Personal Resonance – Transcendent Empathy

Each time I listen to this music, I’m led to contemplate the finitude of life. The despair and longing that Mahler must have felt as a father who lost his daughter, the complex emotions he must have harbored while sensing his own death, are transmitted directly. But it’s not simple sadness.

Rather, this music bestows the special tranquility that comes from the process of accepting death. The liberation that comes when acknowledging that everything must end someday, the preciousness of life discovered within finitude.

Sometimes there are moments when we realize how precious the small moments of daily life are—a morning cup of coffee, the tree visible outside the window, conversation with loved ones. Mahler’s fourth movement conveys exactly such realizations through music.

Suggestions for Deep Appreciation

Securing Adequate Time

This music must not be rushed. Set aside at least 30 minutes, and focus solely on the music without doing anything else. Especially the nearly silent final six minutes must be heard to the end. That’s where the true meaning of this music lies hidden.

Good Acoustic Environment

If possible, I recommend listening with good speakers or headphones. This is to avoid missing the subtle changes in timbre and dynamics that Mahler carefully arranged for each instrument. Especially to hear the subtle timbral changes of the strings and the extremely quiet sounds of the final section, a good reproduction environment is essential.

Understanding Personal Context

If you listen while knowing Mahler’s personal history—his daughter’s death, his own heart disease diagnosis, his expulsion from work—the music will resonate much more deeply. This is not abstract music, but a confession containing one human being’s desperate feelings.

A Message of Farewell Transcending Time

Mahler’s Symphony No. 9, fourth movement, is not merely music from over a century ago. It is a universal reflection on the farewell that every human must someday face. While dealing with the theme of death, it ultimately awakens us more deeply to the meaning of life.

In the process where music gradually diminishes toward silence, we come to realize something important. The value of things made more precious because they have an end, things we must love more because we might lose them.

Mahler once said during his lifetime: “What I make music from is still the whole human being who feels and thinks and breathes and suffers.” Within the fourth movement of Symphony No. 9, all these human emotions flow in a sublimated form. And within that flow, we discover something that transcends death, a beauty that surpasses time.

An Invitation to the Next Journey – Clara Schumann’s Delicate World

After completing Mahler’s grand meditation on death, I would like to invite you to beauty of an entirely different dimension. Clara Schumann’s “Three Romances for Violin and Piano, Op. 22,” No. 1 “Andante molto,” in contrast to Mahler’s sublime tragedy, embraces us with delicate and intimate lyricism.

This work, showing the essence of 19th-century German Romanticism, was composed during the period when Clara’s love with Robert Schumann was at its peak. The acoustic intimacy created by the violin’s sweet melody interweaving with the piano’s delicate accompaniment returns our hearts to the precious moments of daily life after Mahler’s cosmic meditation.

If Mahler’s fourth movement was a reflection on the meaning of existence viewed from life’s end, Clara’s Romance sings of moments of love and happiness discovered in the midst of life. The precious everyday that comes after grandeur, the recovery of warm humanity that follows sublimity.

Listening to both works in succession, you will experience the infinite spectrum of emotions that classical music embraces.