📑 Table of Contents

- The Aria Everyone Knows (But Nobody Really Knows)

- Meet Lauretta: Opera’s Original Drama Queen

- What She’s Actually Singing (It’s Wild)

- Puccini’s Only Comedy (And His Darkest Joke)

- Why This Two-Minute Aria Hits Different

- The Recordings That Define This Aria

- Finding the Aria in Unexpected Places

- How to Listen: A Brief Guide

- The Composer Behind the Curtain

- Final Thoughts: The Beauty of Being Fooled

Have you ever heard a piece of music so heartbreakingly beautiful that you assumed it must be about tragic love or devastating loss? What if I told you one of opera’s most tender melodies is actually about a teenage girl throwing a dramatic tantrum—threatening to drown herself in a river unless her father lets her marry the boy she likes?

Welcome to the wonderfully twisted world of “O mio babbino caro.”

The Aria Everyone Knows (But Nobody Really Knows)

You’ve almost certainly heard this melody before. It’s the one that plays in wedding videos, appears in perfume commercials, and makes people tear up without understanding a single Italian word. When soprano Renée Fleming sings it, audiences reach for tissues. When it appeared in the opening scene of Pixar’s Luca (2021), parents everywhere suddenly found themselves explaining opera to confused children.

But here’s the delicious irony: this “beautiful love song” is neither a love song nor particularly beautiful in its intentions. It’s emotional blackmail set to music—and Puccini knew exactly what he was doing.

Meet Lauretta: Opera’s Original Drama Queen

The year is 1299. The setting is Florence, Italy—specifically, the bedroom of a recently deceased wealthy man named Buoso Donati. His greedy relatives have just discovered that Buoso left his entire fortune to a monastery. Cue family chaos.

Enter Gianni Schicchi, a clever outsider who agrees to impersonate the dead man and dictate a new will. But there’s a catch: Schicchi’s young daughter Lauretta is desperately in love with Rinuccio, one of the Donati heirs. The family disapproves. Tensions rise.

And then Lauretta drops to her knees.

What She’s Actually Singing (It’s Wild)

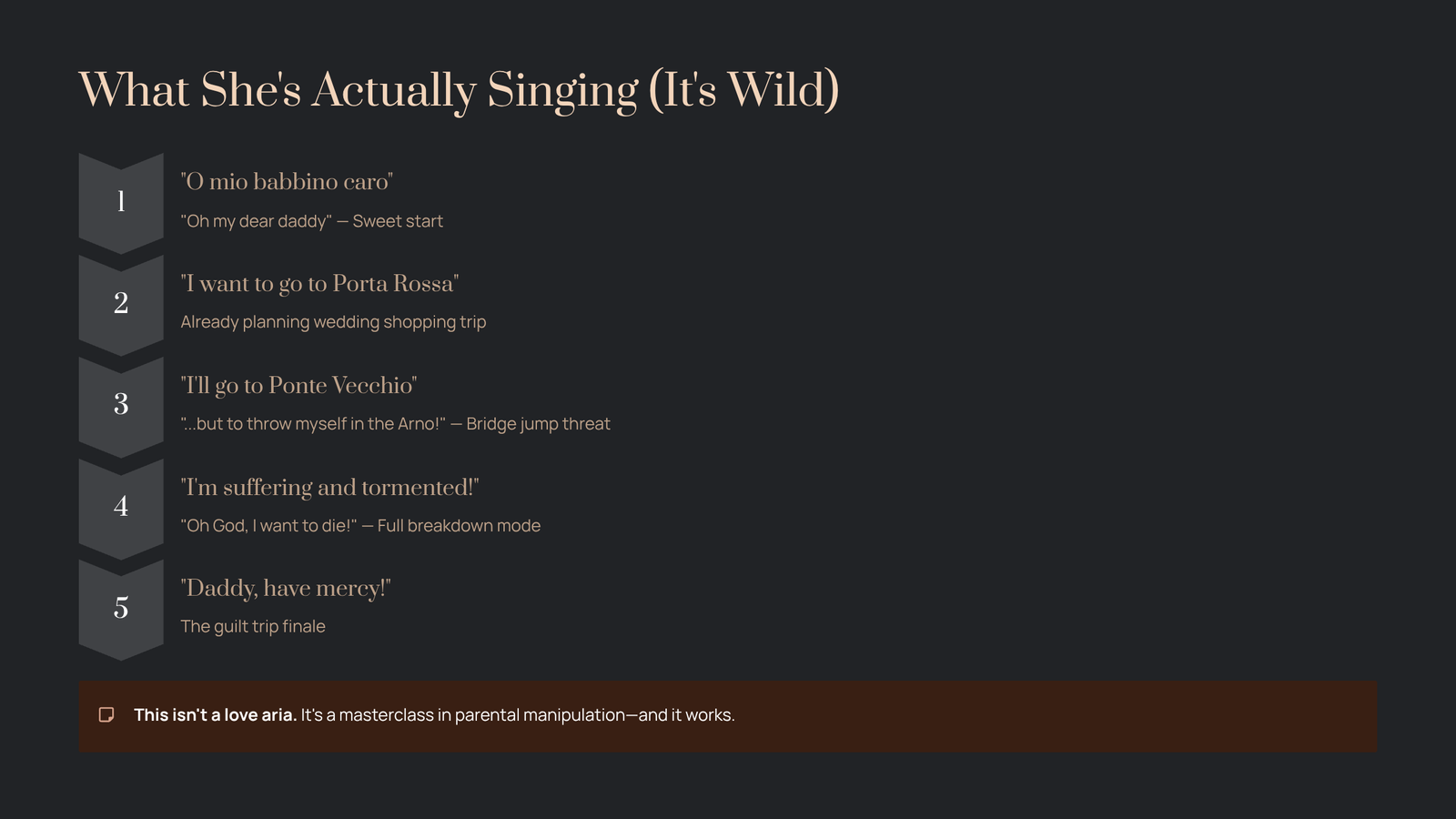

Let me translate the key moments for you:

“O mio babbino caro” — “Oh my dear daddy”

So far, so sweet. But wait.

“I want to go to Porta Rossa to buy the ring!” — She’s already planning her wedding shopping trip.

“And if my love is in vain, I’ll go to the Ponte Vecchio… but to throw myself in the Arno!” — That’s right. She’s threatening to jump off Florence’s most famous bridge into the river below.

“I’m suffering and tormented! Oh God, I want to die!” — Full dramatic breakdown mode.

“Daddy, have mercy! Have mercy!” — The guilt trip finale.

This isn’t a love aria. It’s a masterclass in parental manipulation—and it works. Schicchi agrees to help the family, Lauretta gets her man, and audiences have been swooning over this “innocent” melody for over a century.

Puccini’s Only Comedy (And His Darkest Joke)

Giacomo Puccini was the master of operatic tragedy. La Bohème ends with Mimì dying of tuberculosis. Madama Butterfly concludes with a suicide. Tosca features murder, torture, and a woman leaping to her death.

So when Puccini announced he was writing a comedy in 1917, everyone was intrigued. Gianni Schicchi premiered at the Metropolitan Opera on December 14, 1918, as part of a triple bill called Il trittico. The audience response was immediate: they loved it.

Here’s Puccini’s genius: he took a character that Dante condemned to hell for fraud (yes, Gianni Schicchi appears in the Inferno) and made him sympathetic. He took a spoiled teenager’s tantrum and turned it into one of the most beautiful melodies ever written. The joke is on us—we’re moved to tears by emotional manipulation, and we love every second of it.

Why This Two-Minute Aria Hits Different

From a purely musical standpoint, “O mio babbino caro” is deceptively simple. The key is A-flat major—warm and embracing. The tempo marking is “Andantino ingenuo,” which literally means “at a walking pace, innocently.” Puccini is telling the soprano: sound naive. Sound guileless. Sound like a child.

The melody follows an arch shape, rising gently before falling back down, like a sigh or a plea. The harp provides a delicate, almost music-box accompaniment. Everything about the orchestration says “pure and innocent,” while the lyrics say “I will literally jump off a bridge.”

The climax comes on the word “bello” (beautiful), where the soprano leaps up an entire octave—from A-flat to high A-flat. It’s the musical equivalent of a teenage girl’s voice cracking with desperation. And then, in the original score, the piece ends quietly, descending back down. Lauretta isn’t shouting her demands; she’s whimpering them. It’s far more effective.

The Recordings That Define This Aria

If you’re ready to experience “O mio babbino caro” properly, here are some legendary interpretations:

Maria Callas (1959, with Tullio Serafin): The gold standard. Callas understood Lauretta’s manipulation and sang with a knowing innocence—childlike but calculated. Her version ends low, as Puccini intended, preserving the character’s youth.

Kiri Te Kanawa: Described by critics as “perfection.” Her warm, creamy tone makes the aria feel like being wrapped in a cashmere blanket. Pure emotional comfort.

Montserrat Caballé: Known for incredible breath control and space between phrases. She stretches the melody like taffy, finding colors other sopranos miss.

Renée Fleming (2010, Berlin Philharmonic): The modern benchmark. Fleming’s version is polished, romantic, and unapologetically beautiful—perhaps losing some of the character’s edge but gaining universal appeal.

For the historically curious, Florence Easton’s 1919 recording exists—she was the original Lauretta at the world premiere. It’s a glimpse into how audiences first heard this melody.

Finding the Aria in Unexpected Places

One reason “O mio babbino caro” endures is its remarkable versatility. Directors keep finding new contexts for its emotional power:

In A Room with a View (1985), it underscores the romantic tension of Helena Bonham Carter’s journey through Florence—the very city where the opera is set. The final scene uses the complete aria.

In Disney Pixar’s Luca (2021), two fishermen play it on a phonograph before a sea monster knocks it into the water. It’s a playful introduction to the film’s Italian coastal setting.

It’s appeared in Captain Corelli’s Mandolin, The Simpsons, Alvin and the Chipmunks, and even the trailer for Grand Theft Auto III. Olympic figure skaters have performed to it. McDonald’s used it in a 2024 commercial.

The aria has transcended opera. It’s become shorthand for “beautiful classical music”—which is either wonderful or slightly absurd, depending on whether you know a teenage girl is threatening suicide.

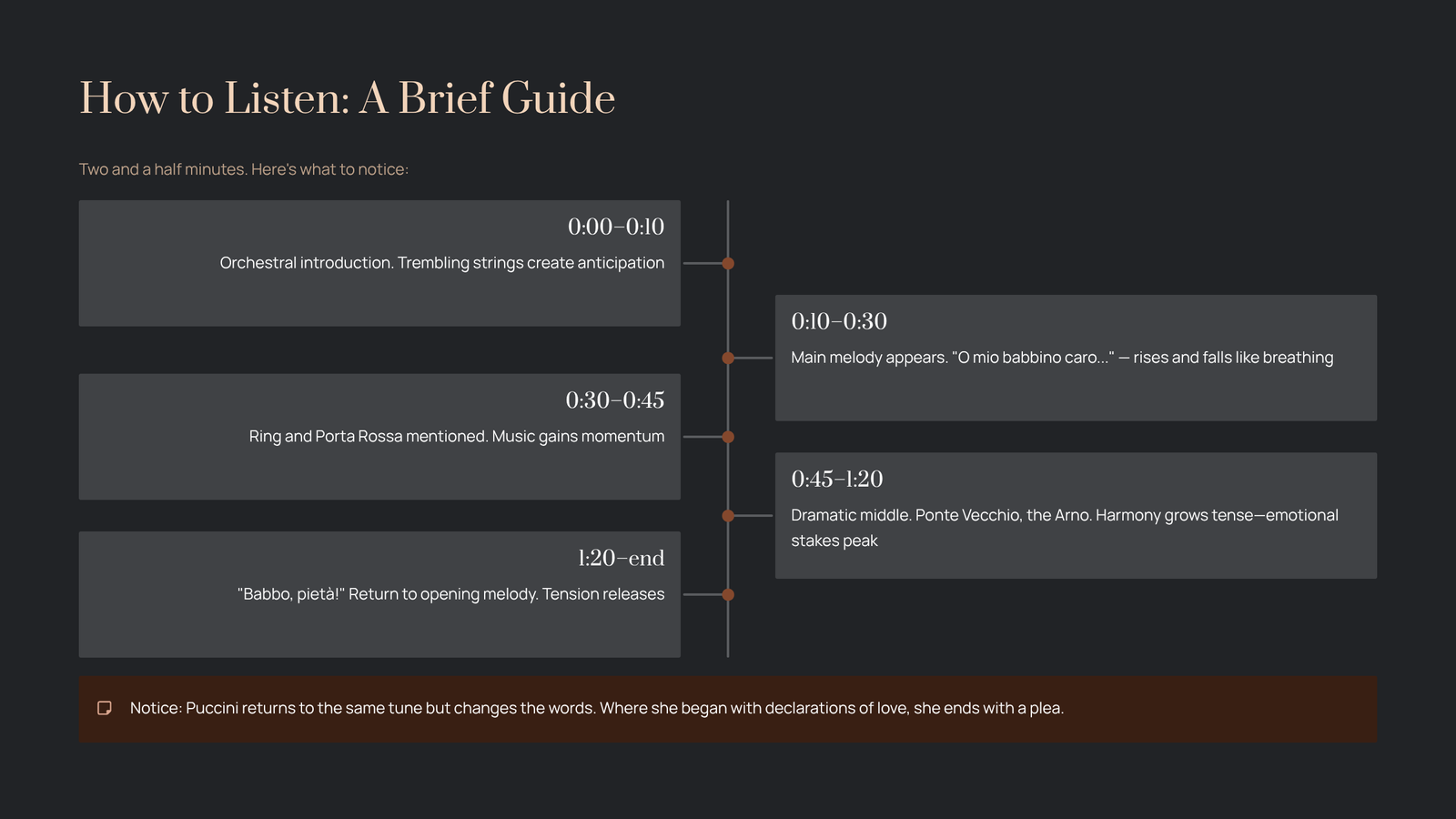

How to Listen: A Brief Guide

If you have two and a half minutes (that’s really all it takes), here’s what to notice:

0:00–0:10: The orchestral introduction. Trembling strings create anticipation. Something important is about to happen.

0:10–0:30: The main melody appears. “O mio babbino caro…” Listen to the shape of the phrase—it rises and falls like breathing.

0:30–0:45: She mentions the ring and Porta Rossa (a real building in Florence, still standing today). The music gains momentum.

0:45–1:20: The dramatic middle section. The melody becomes more urgent as she mentions Ponte Vecchio and the Arno. The harmony grows tense. This is where the emotional stakes peak.

1:20–end: Return to the opening melody, but now with “Babbo, pietà!” (Daddy, have mercy!). The tension releases. Resolution.

Notice how Puccini returns to the same tune at the end but changes the words. Where she began with declarations of love, she ends with a plea. The music is circular; the emotion escalates.

The Composer Behind the Curtain

Giacomo Puccini finished Gianni Schicchi in April 1918, during one of history’s darkest periods. World War I was grinding toward its end. The Spanish flu pandemic was beginning to sweep the globe—it would eventually kill Puccini’s own sister.

Yet here was Puccini, writing a comedy. Writing beauty. Writing an aria about young love and family drama while the world was falling apart.

Perhaps that’s why the piece resonates so deeply. It’s not naive—Puccini wasn’t naive. It’s deliberately, defiantly hopeful. In the middle of an opera about death, greed, and deception, a young girl sings about wanting to buy a wedding ring. Life goes on. Love persists. Even if you have to emotionally blackmail your father to get there.

Final Thoughts: The Beauty of Being Fooled

Every time I listen to “O mio babbino caro,” I’m struck by how completely Puccini manipulates us. We know Lauretta is being dramatic. We know her threats are empty. We know we’re being played by both the character and the composer.

And we don’t care.

That’s the power of great music. It bypasses our cynicism and speaks directly to something older and deeper. When that soprano voice soars on “bello,” something inside us lifts too. When she pleads “pietà,” we want to grant it.

So the next time you hear this melody in a commercial or a movie, remember: you’re listening to a teenage girl’s tantrum, immortalized by a genius who understood that the line between manipulation and sincerity is thinner than we’d like to admit.

And maybe that’s the most human thing about it.