📑 Table of Contents

- The Composer Behind the Toast

- A Catastrophic Premiere and Prophetic Confidence

- Understanding the Scene: Champagne and Shadow

- The Music: Waltz Rhythm with Hidden Depths

- A Listening Guide: Three Ways to Experience the Brindisi

- Recommended Recordings: Voices That Make the Toast Sing

- The Brindisi in Popular Culture

- The Paradox of Celebration

There’s a moment in every great party when someone raises a glass and the room falls silent. In that suspended breath before the toast, something almost sacred happens—strangers become companions, and the ordinary night transforms into memory. Giuseppe Verdi understood this moment better than perhaps any composer in history. His “Libiamo ne’ lieti calici,” known simply as the Brindisi from La Traviata, captures not just the sparkle of champagne but something far more profound: the desperate beauty of celebrating life while knowing it cannot last.

The Composer Behind the Toast

Giuseppe Verdi was forty years old when he composed La Traviata in 1852-1853, and he was at the peak of his creative powers. Living in the Italian countryside at Sant’Agata with his partner Giuseppina Strepponi, Verdi had achieved both artistic recognition and financial security. Yet beneath this comfortable surface, the composer harbored restless ambitions.

During a visit to Paris in early 1852, Verdi attended a performance of Alexandre Dumas fils’s play La Dame aux Camélias—the story of a Parisian courtesan dying of tuberculosis. The experience struck him like lightning. Here was a story not of distant kings or mythological heroes, but of contemporary life: love, illness, social hypocrisy, and death in the very world he inhabited.

Verdi immediately began working on an opera that would shock nineteenth-century sensibilities. He wanted to set the story in modern dress, to put a woman of questionable virtue at the center of tragedy, and to make audiences weep for her. The censors and theater management pushed back, eventually forcing him to set the action in the past. But Verdi’s vision remained revolutionary.

A Catastrophic Premiere and Prophetic Confidence

When La Traviata premiered at Venice’s Teatro La Fenice on March 6, 1853, it was a disaster. The soprano cast as Violetta—Fanny Salvini-Donatelli—was, by contemporary accounts, ill-suited for the role of a delicate, dying courtesan. The tenor had a cold. The audience laughed during the death scene.

The next morning, Verdi wrote to a friend with remarkable composure: “La Traviata last night a failure. Was the fault mine or the singers’? Time will tell.” Then he added a prediction: “I am convinced that within a year, Traviata will triumph.”

He was right. Just fourteen months later, a revised production with a new cast played to rapturous audiences at Venice’s Teatro San Benedetto. The publisher Tito Ricordi reported that it was “a success surpassing anything in the history of Venice.” Within three years, the opera had conquered stages across Europe. Today, it remains one of the most performed operas in the world.

Understanding the Scene: Champagne and Shadow

The Brindisi occurs early in Act I, during a lavish party at Violetta’s Parisian salon. The beautiful courtesan is hosting her usual gathering of aristocrats, artists, and admirers. Among them is Alfredo Germont, a young man who has secretly loved her from afar for years. Encouraged by a mutual friend, Alfredo is persuaded to offer a toast.

What begins as a simple drinking song becomes something far more complicated. As Alfredo sings “Let us drink from the joyful cups that beauty adorns,” he’s not merely celebrating wine—he’s declaring his love, disguising passion as party entertainment. When Violetta responds with her own verse, she speaks of seizing pleasure because “love is a flower that blooms and dies.”

This is the bitter irony Verdi embedded in his most famous tune: Violetta is dying of tuberculosis. Every word about fleeting pleasure, every phrase about enjoying the moment before it passes, carries the weight of her mortality. The audience knows what the party guests do not. The champagne is real, but so is the shadow.

The Music: Waltz Rhythm with Hidden Depths

Verdi set the Brindisi in B-flat major—a bright, celebratory key—with a 3/8 waltz rhythm that immediately evokes Parisian ballrooms and swirling dancers. The tempo marking is Allegretto, quick enough to feel festive but not frantic. The orchestration sparkles: strings provide a bouncing “oom-pah-pah” accompaniment while clarinets and flutes double the melody for brilliance.

The structure follows the traditional brindisi form: one character begins the toast, another responds, and the chorus joins in celebration. Alfredo’s opening melody rises with bold confidence, each phrase building energy. When Violetta takes over, she sings in a higher register, adding ornamental flourishes that make the same tune feel simultaneously more elegant and more fragile.

But listen carefully to a passage about midway through Alfredo’s verse, on the words “poiché quell’occhio al core” (“since those eyes speak to my heart”). Here Verdi briefly darkens the harmony, shifting toward minor colors. It’s a momentary shadow, almost imperceptible amid the sparkle, yet it hints at the depths beneath the surface gaiety. This is Verdi’s genius: even in his most accessible music, emotional complexity lurks.

A Listening Guide: Three Ways to Experience the Brindisi

First listening: Pure enjoyment. Don’t analyze—simply let the music wash over you. Notice how the melody immediately lodges in your memory, how your foot starts tapping, how the call-and-response between soloists and chorus creates infectious energy. This is why the Brindisi works at flash mobs and wedding receptions: it’s irresistibly fun.

Second listening: Follow the drama. Now pay attention to who sings what. Alfredo begins the toast—why him, a newcomer to this salon? Because he’s using the occasion to declare himself. When Violetta responds, notice how her words about fleeting pleasure aren’t just party philosophy but personal confession. When the chorus joins, hear how individual emotion becomes collective celebration—and how that collective joy might mask individual pain.

Third listening: Hear the orchestra. Focus on what happens beneath the voices. The strings maintain that perpetual waltz motion like a heartbeat. The brass punctuate moments of climax. Notice how Verdi gradually increases the orchestral intensity as the piece progresses, building toward a triumphant conclusion. Yet even at the peak of celebration, the music retains an almost breathless quality, as if everyone knows the party cannot last forever.

Recommended Recordings: Voices That Make the Toast Sing

The legendary 1994 Three Tenors concert at Los Angeles’ Dodger Stadium offers perhaps the most exuberant Brindisi ever recorded. Luciano Pavarotti, Plácido Domingo, and José Carreras trade verses with obvious joy, and there’s a wonderful moment around the 1:19 mark where Domingo attempts something technically adventurous and his colleagues exchange looks of amused admiration. It’s not authentic opera—it’s better for parties.

For the full dramatic context, Maria Callas’s 1958 studio recording with the Orchestra del Teatro alla Scala brings heartbreaking dimension to Violetta’s verses. Callas understood that this character is already dying when she raises her glass, and you can hear knowledge of mortality in every phrase.

Among complete opera recordings, the 1977 Carlos Kleiber version with Ileana Cotrubas as Violetta captures both the champagne sparkle and the shadows beneath. Kleiber’s conducting finds that perfect tempo where celebration feels genuine but also slightly desperate—as if everyone knows the clock is ticking.

The Brindisi in Popular Culture

Few pieces of classical music have traveled as far from the opera house as the Brindisi. You might recognize it from the film Pretty Woman, where Julia Roberts’s character attends La Traviata and finds herself unexpectedly moved. (The movie draws explicit parallels between Violetta and the modern call girl finding love.)

Heineken beer has used the Brindisi in advertising campaigns—the connection between drinking songs and beer marketing requires no explanation. Flash mob performances pop up regularly at shopping centers, Italian festivals, and public squares worldwide, bringing opera’s most famous toast to unsuspecting shoppers.

Yet something gets lost in these popular appropriations. The Brindisi is not merely a happy drinking song. Its genius lies in the tension between surface joy and underlying tragedy. When we hear it ripped from context, we get the champagne without the shadow—pleasure without depth.

The Paradox of Celebration

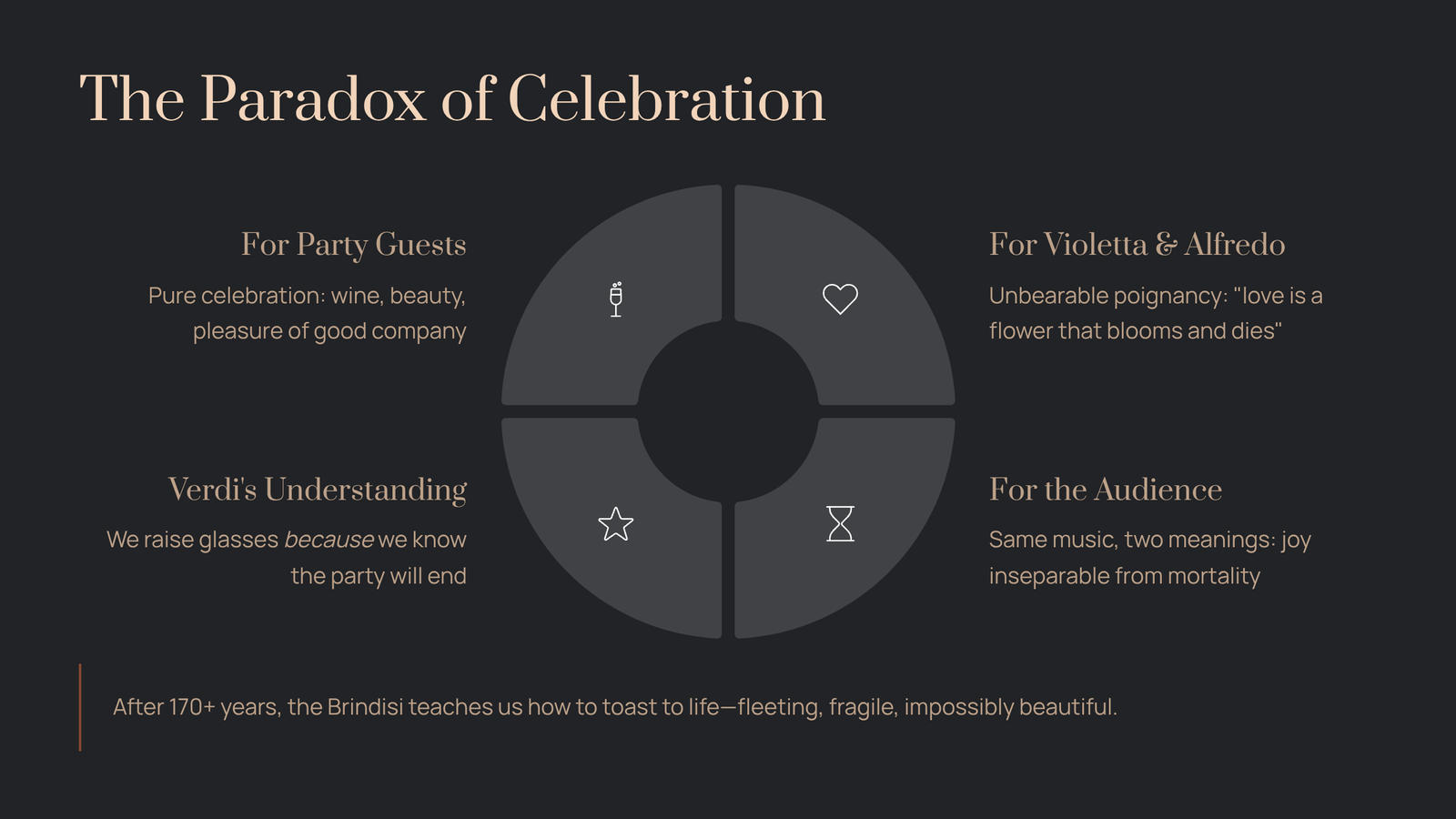

Here is what makes the Brindisi genuinely great, beyond its catchy tune and brilliant orchestration: Verdi created a piece of music that means two entirely different things simultaneously.

For the characters onstage—the party guests, the chorus—this is pure celebration. Wine, beauty, the pleasure of good company on a Parisian night.

For Violetta and Alfredo—and for us in the audience who know what’s coming—the same music carries unbearable poignancy. “Enjoy the fleeting moment,” Violetta sings, “for love is a flower that blooms and dies.” She’s not offering party wisdom. She’s describing her own life.

This is why the Brindisi continues to move audiences after more than 170 years. Verdi understood something essential about human experience: our most joyful moments are inseparable from our awareness of mortality. We raise our glasses precisely because we know the party will end. We celebrate because time is passing.

The next time you hear those famous opening bars—at a wedding, in a commercial, emerging from a flash mob at your local shopping center—remember what lies beneath the sparkle. Someone is dying. Someone is falling in love. And everyone, whether they know it or not, is dancing toward the end of the song.

That’s not depressing. That’s what makes raising a glass worth doing. Verdi knew this. After more than a century and a half, the Brindisi still teaches us how to toast to life—fleeting, fragile, and impossibly beautiful.

Listening suggestion: After experiencing the Brindisi, continue with the full Act I of La Traviata. Immediately following the drinking song, Violetta suddenly falls ill, and her conversation with Alfredo reveals the depth of feeling hidden beneath the party’s surface. The contrast between celebration and crisis is devastating—and that’s exactly what Verdi intended.