📑 Table of Contents

In September 1850, Robert Schumann stood at the banks of the Rhine River, a man reborn. After years of financial uncertainty and failed career attempts, he had finally secured a stable position as music director in Düsseldorf. The majestic river stretched before him, its currents carrying centuries of German folklore, vineyard-covered hills reflecting in its waters. Within weeks, he would pour this euphoria into music—a symphony so radiant that listeners still feel its warmth 175 years later.

What Schumann couldn’t know was that four years later, he would throw himself into this same river, attempting to end his own life.

The “Rhenish” Symphony, particularly its exhilarating first movement, captures a man at the peak of hope. Understanding this context transforms every note from mere sound into emotional testimony.

A Fresh Start on the Riverbank

The year 1850 marked a turning point in Schumann’s troubled life. He had desperately wanted the prestigious music director position in Leipzig, but that door remained closed. Düsseldorf was, truthfully, his fourth choice. Yet when he arrived with his wife Clara and their seven children, the Rhineland embraced them with open arms—lavish banquets, celebratory concerts, and serenades from hotel balconies.

Something shifted in Schumann’s spirit. The rolling vineyards, the ancient Cologne Cathedral rising against the sky, the cheerful folk songs echoing through riverside taverns—all of it awakened a creative energy he hadn’t felt in years. In a letter to his publisher, he confessed that this symphony would “reflect something of Rhineland life.”

Then, remarkably, he composed the entire work in just five weeks. From November 2 to December 9, 1850, music poured out of him like the river itself—unstoppable, life-giving, magnificent.

What Makes This Movement So Alive

The first movement, marked “Lebhaft” (meaning “lively” or “vivaciously”), wastes no time with introductions. From the very first measure, the full orchestra erupts in a heroic theme that seems to say: Life is good, and I’m finally ready to live it.

Here’s what makes this music so uniquely captivating. Schumann plays a rhythmic trick on your ears. The piece is written in 3/4 time—a waltz-like triple meter—but the melody phrases themselves suggest a slower, broader pulse. Music theorists call this “hemiola,” but you don’t need the technical term to feel it. Your foot might start tapping at one speed, only to realize the music is actually moving at another. This creates an irresistible forward momentum, as if the symphony itself cannot wait to tell you its story.

The opening theme is built on what musicians call the “perfect fourth”—a simple interval that sounds like the beginning of “Here Comes the Bride.” Schumann stacks these fourths in descending and ascending patterns, creating a musical architecture as solid and awe-inspiring as the Cologne Cathedral that inspired him.

Two Sides of Rhineland Life

Listen carefully, and you’ll notice the movement contains two distinct personalities. The first theme—bold, heroic, almost Beethoven-like—represents the grandeur of the Rhine itself, that mighty natural force flowing through German history. The horns soar above the orchestra here, their sound evoking hunting parties in the surrounding forests.

But then comes the second theme, introduced gently by oboes and clarinets. This melody is softer, more intimate—the sound of village life, of wine festivals and quiet evenings by the water. It’s as if Schumann is showing us both the public magnificence and private joys of his new home.

Interestingly, this second theme bears a striking resemblance to the main theme of Brahms’s Third Symphony, composed decades later. This wasn’t coincidence. The young Brahms spent time in the Schumann household in 1853, and the musical connections between these two composers run deep. When Brahms wrote his own “Rhenish” symphony (he was living near the Rhine at the time), the ghost of Schumann’s melody seems to have visited him.

Where to Focus Your Listening

If you’re new to this symphony, here’s a simple guide for your first listen.

The opening thirty seconds set everything in motion. Notice how the music feels both urgent and spacious simultaneously—that’s the hemiola magic at work. Let yourself be swept up in its confidence.

Around the two-minute mark, listen for the color change when woodwinds introduce the gentler second theme. The brass steps back, the texture thins, and suddenly we’re in a completely different emotional landscape.

The development section (roughly the middle third of the movement) takes these themes on a journey through various keys. The music becomes more unstable here, more searching. Schumann breaks his themes into fragments, rearranging them like a kaleidoscope. Don’t worry about following every detail—just notice the sense of exploration, of not quite knowing where we’re headed.

Then comes the triumphant return. The main theme blazes back in the home key, and there’s a palpable feeling of arrival, of coming home after a long journey. This moment captures what the Rhine meant to Schumann: a place where he finally belonged.

Recommended Recordings

For your first encounter with this movement, Leonard Bernstein’s 1960 recording with the New York Philharmonic offers youthful energy and romantic passion in equal measure. Bernstein understood the emotional stakes of this music—perhaps because he, too, struggled with mental health throughout his life.

If you prefer a more polished, technically refined approach, Herbert von Karajan’s recordings showcase orchestral precision and beautiful sound. Some find this approach too controlled, but there’s no denying the sheer sonic pleasure.

For a modern perspective, Paavo Järvi’s cycle with the Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen brings transparency and clarity to Schumann’s dense orchestration. You’ll hear inner voices and details that other recordings sometimes obscure.

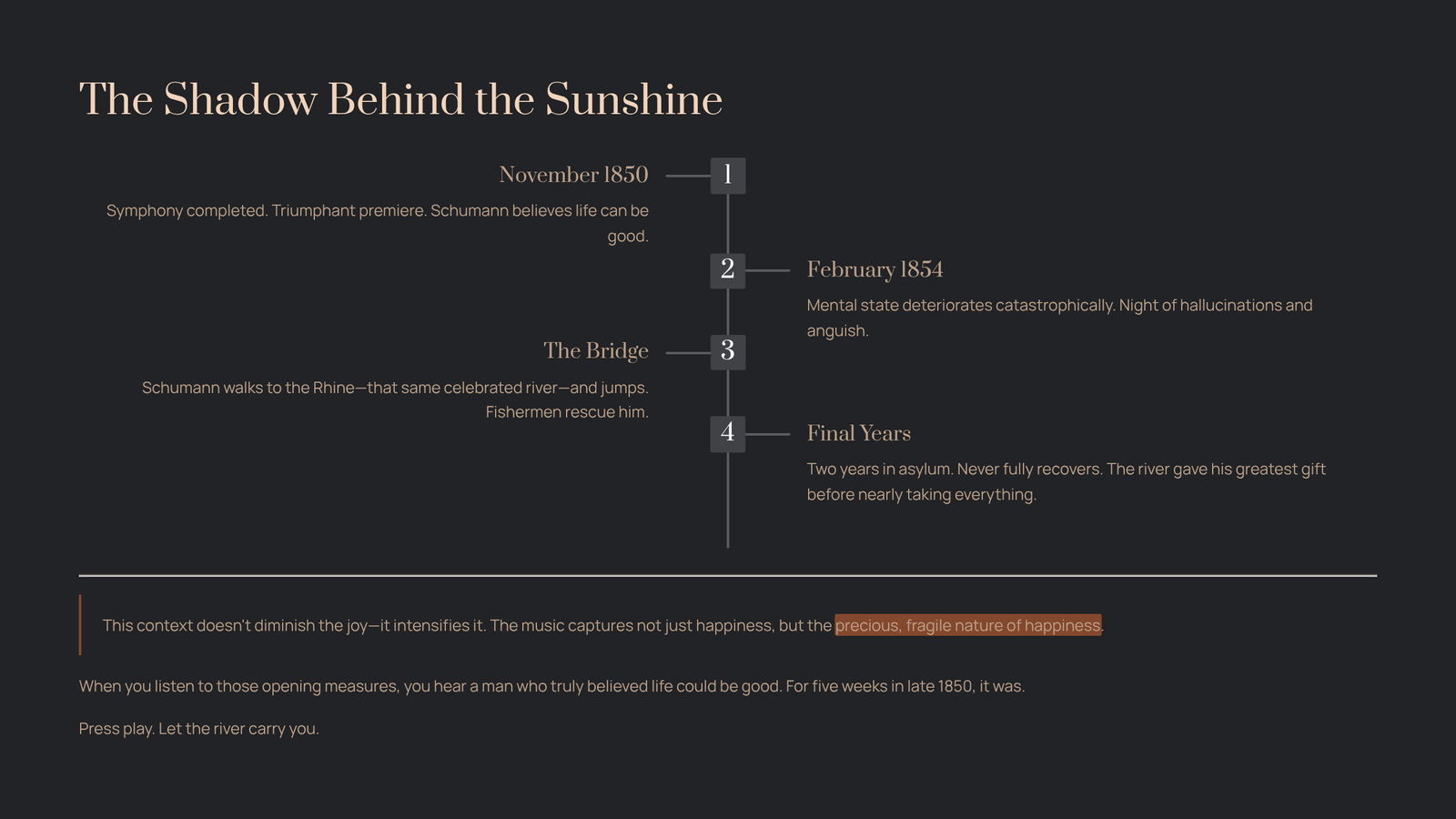

The Shadow Behind the Sunshine

We cannot fully appreciate this music without acknowledging what came after. In February 1854, just three years after this symphony’s triumphant premiere, Schumann’s mental state deteriorated catastrophically. During a night of hallucinations and anguish, he walked to a bridge over the Rhine—that same river he had celebrated so gloriously—and jumped.

Fishermen pulled him from the water. He spent his final two years in an asylum, never fully recovering.

This context doesn’t diminish the joy in the “Rhenish” Symphony. If anything, it intensifies our experience of it. The first movement captures not just happiness, but the precious, fragile nature of happiness—how a human being can find genuine peace and creative fulfillment, even when darkness waits in the wings.

When you listen to those opening measures, you’re hearing a man who truly believed life could be good. For those five weeks in late 1850, it was. The Rhine gave Schumann one of his greatest gifts before it nearly took everything away.

That tension between light and shadow, between hope and tragedy, is what makes this music so profoundly human. It asks us to celebrate joy while we have it, to pour our whole hearts into the beautiful moments, because we never know how long they’ll last.

Press play. Let the river carry you.