Table of Contents

The First Encounter, That Trembling Moment

Some music captures your body from the very first measure. Brahms’ Hungarian Dance No. 1 is precisely such a piece. Think back to when you first encountered this composition. Perhaps your shoulders began moving involuntarily, your feet tapping against the floor.

That opening melody bursting from the darkness of G minor feels both familiar and intense, as if it had been waiting for you all along. This is not merely a simple dance. It is an emotional record transcending time and space—a 19th-century German composer translating the whisper of winds from Hungarian plains onto staff paper.

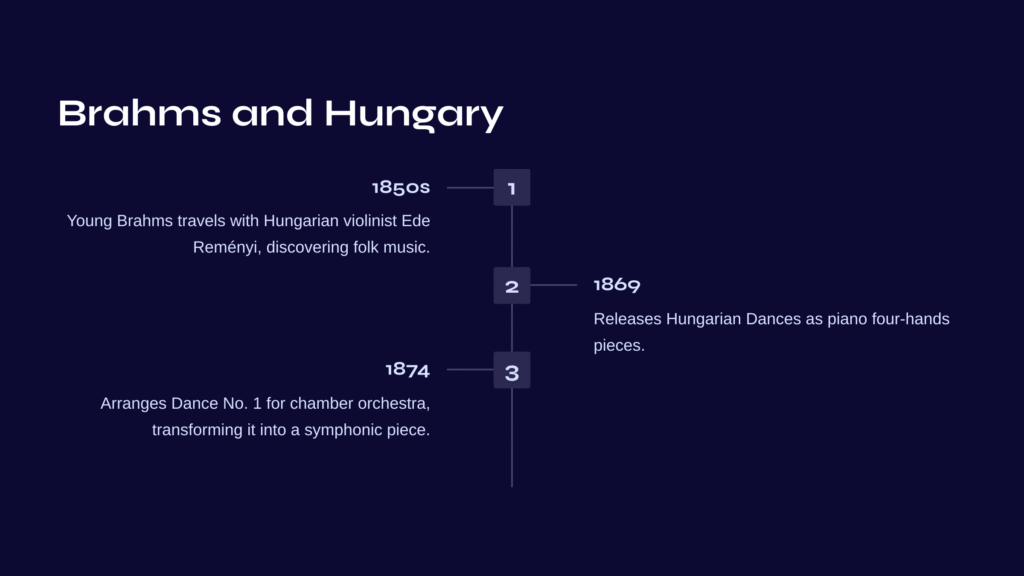

Brahms and Hungary, A Fateful Meeting

The Hungarian Dances that Johannes Brahms released to the world in 1869 represented one of the most fascinating adventures of his life. In the 1850s, young Brahms traveled with Hungarian violinist Ede Reményi, first stepping into the world of Hungarian folk music.

What he heard then was not simple melody. It was the emotional contrast created by the slow section “lassan” and fast section “friska” of the csárdás, and the rhythmic magic of verbunkos dances whose beginning and end remained unknowable. Brahms felt these melodies touching something deep within his heart.

Hungarian Dance No. 1 was originally born as a piano four-hands piece. The rich sonority created by two performers seated at one piano was sufficient to imitate that of an orchestra. But Brahms did not stop there. In 1874, he personally arranged this piece for chamber orchestra. In that moment, this small dance was reborn as a truly symphonic dance piece.

Journey into Sound – The Intimate Structure of the Music

The Thrill of Beginning

From the first measure, Brahms binds us captive. The dotted rhythm bursting from G minor’s darkness is both regular and unpredictable, like the sound of horse hooves. This is precisely “alla zoppa”—the “limping” rhythm. The instability created by breaking the normal order of strong and weak beats becomes the very life force of this dance.

The opening theme played in unison by strings appears simple, but hidden within are the ornamental notes of Hungarian folk violin. The freedom of that moment when a gypsy musician plucks the strings is amplified and resonates through the massive instrument that is the orchestra.

The Magic of Development and Variation

As the piece progresses, Brahms unfolds amazing variations with this simple theme. When the woodwinds take over the subject, the color changes completely. The bright timbre of the flute suggests the sound of wind across fields, while the warmth of the clarinet evokes the gentle heat of an evening sunset.

Most impressive are the sudden dynamic changes. The moment when quietly whispering melody suddenly explodes in fortissimo, you witness a festival suddenly beginning in a quiet village square. Such dramatic contrasts are miracles born from the meeting of Brahms’ characteristic romantic sensibility with the primitive energy of Hungarian folk music.

Racing Toward Climax

As the piece moves toward its latter half, rhythms become more complex and tempo accelerates. When the stretto technique is employed—multiple voices playing the same theme at different points—it creates the illusion of several dancers performing the same dance at different timings.

When the sparkling sound of triangle and powerful resonance of timpani are added, the piece finally reaches its peak. In this moment, you discover yourself not merely listening to music, but standing in the midst of some 19th-century Hungarian country festival.

Personal Resonance – The Hungary Within My Heart

Every time I listen to this piece, I always recall the same thing. Memories of summer days spent at my grandmother’s house in childhood. Those moments of tranquility when neighborhood adults gathered in the yard chatting peacefully in the evening, suddenly broken when someone turned on the radio.

Brahms’ Hungarian Dance No. 1 is exactly that kind of music. Music where tranquility and passion coexist, where daily life and festival blend into one. Within this piece lies both the longing for exotic sentiment that Brahms, the German composer, felt, and simultaneously the creative will to translate it into his own musical language.

Above all, the greatest emotion this piece provides is the “erasure of boundaries.” The boundaries between Germany and Hungary, classical and folk music, composition and arrangement, personal emotion and collective memory all disappear. In that moment, we experience pure emotional exchange transcending nations and eras.

Practical Advice for Deep Appreciation

First – Surrender to the Rhythm

The most important thing when appreciating this piece is to listen with your body, not your head. Don’t try to analyze the irregularity of dotted rhythms logically—just let your shoulders move as they will. The “limping” sensation Brahms intended can only be fully understood through experience, not analysis.

Second – Experience Various Versions

I recommend alternating between the original piano four-hands version and Brahms’ own orchestral arrangement. In the piano version you’ll discover more intimate, chamber music-like charm; in the orchestral version, magnificent and colorfully rich abundance. I recommend Claudio Abbado and Vienna Philharmonic’s 1983 recording or Simon Rattle and Berlin Philharmonic’s 2011 version.

Third – Believe in the Power of Repeated Listening

This is not music to be heard once and finished. New details are discovered with each listening. Focus on the overall flow the first time, melody’s beauty the second, rhythmic complexity the third, harmonic sophistication the fourth. Listening while concentrating on different instrumental groups each time is also an excellent approach.

The Message of Timeless Dance

Brahms’ Hungarian Dance No. 1 holds meaning beyond a simple arrangement of folk music. This is the result of cultural dialogue created by an artist based on respect and understanding for another culture. Just as 19th-century Brahms learned the musical language of Hungary and interpreted it in his own way, you reading this text today will experience emotional exchange transcending time and space through this music.

Music is, ultimately, the art of time. But true masterpieces transcend time. Listening to Brahms’ Hungarian Dance No. 1, we share the same emotion with that composer from 1869, and experience the same joy as those anonymous performers from Hungarian plains.

Isn’t this the most amazing magic that classical music possesses? That eternal dance melody connecting different souls across long stretches of time.

Invitation to the Next Journey

Having experienced folk passion through Brahms’ Hungarian Dance, how about journeying to a completely different world? I recommend Rossini’s William Tell Overture Finale, “March of the Swiss Soldiers.”

If Brahms’ dance was an explosion of personal and intimate emotion, Rossini’s march is an expression of collective and magnificent will. From the free dance of Hungarian plains to the dignified march of the Swiss Alps—comparing different visions of freedom that 19th-century Europe dreamed of through music would be a fascinating experience.

Particularly, the contrast that Rossini’s clear and straightforward rhythm provides to ears accustomed to Brahms’ complex and emotional rhythms will be quite striking. Both works deal with the theme of “freedom,” but one sings of personal liberation while the other of collective resolve, making for interesting comparative listening.