📑 Table of Contents

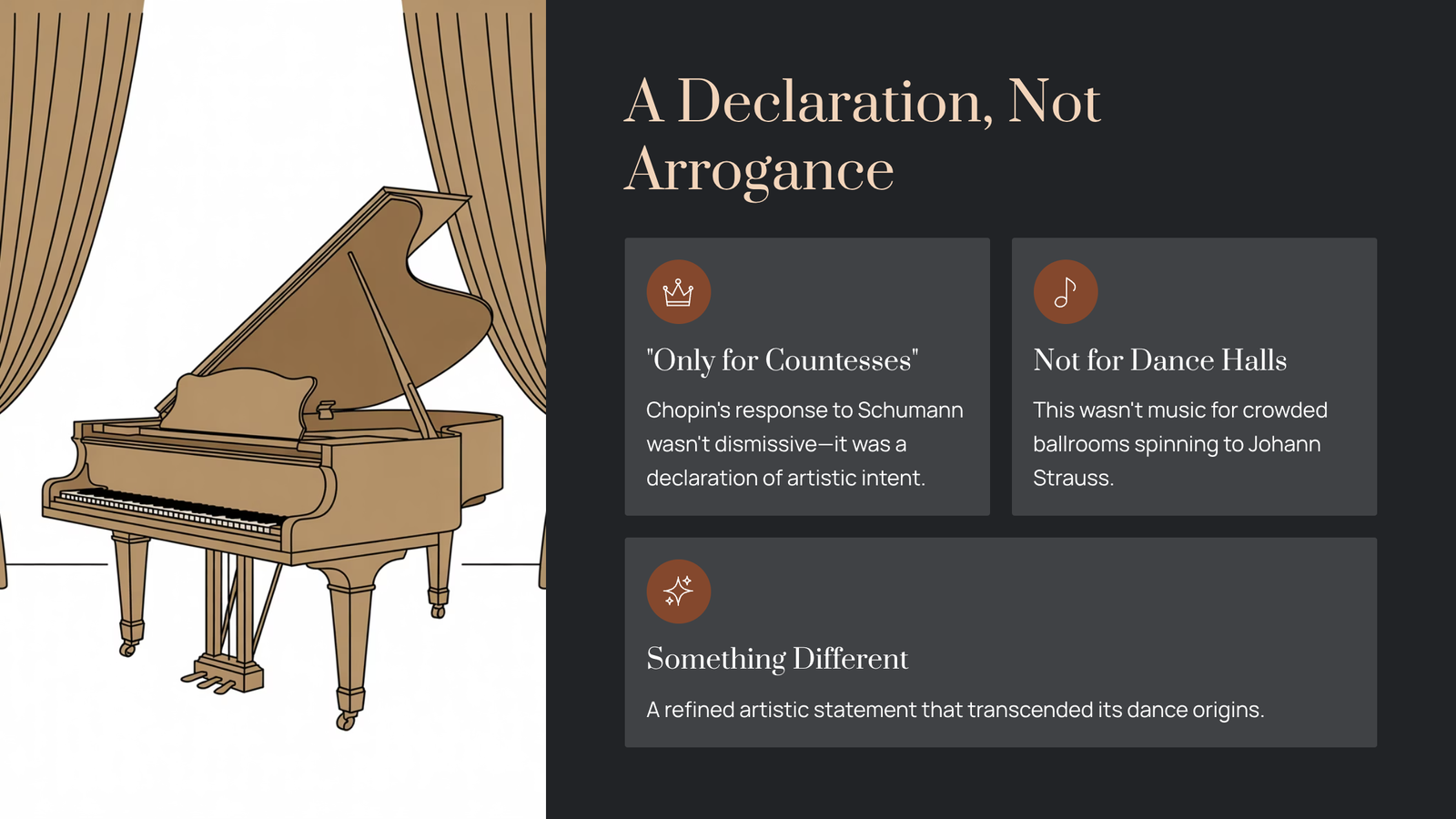

When Robert Schumann asked Chopin about his new waltz, the composer’s answer was almost dismissive: “Only for countesses.” It wasn’t arrogance—it was a declaration. This wasn’t music for crowded dance halls where couples spun to Johann Strauss. This was something entirely different. And that single remark captures everything you need to know about the Grande Valse Brillante in E-flat major, Op. 18.

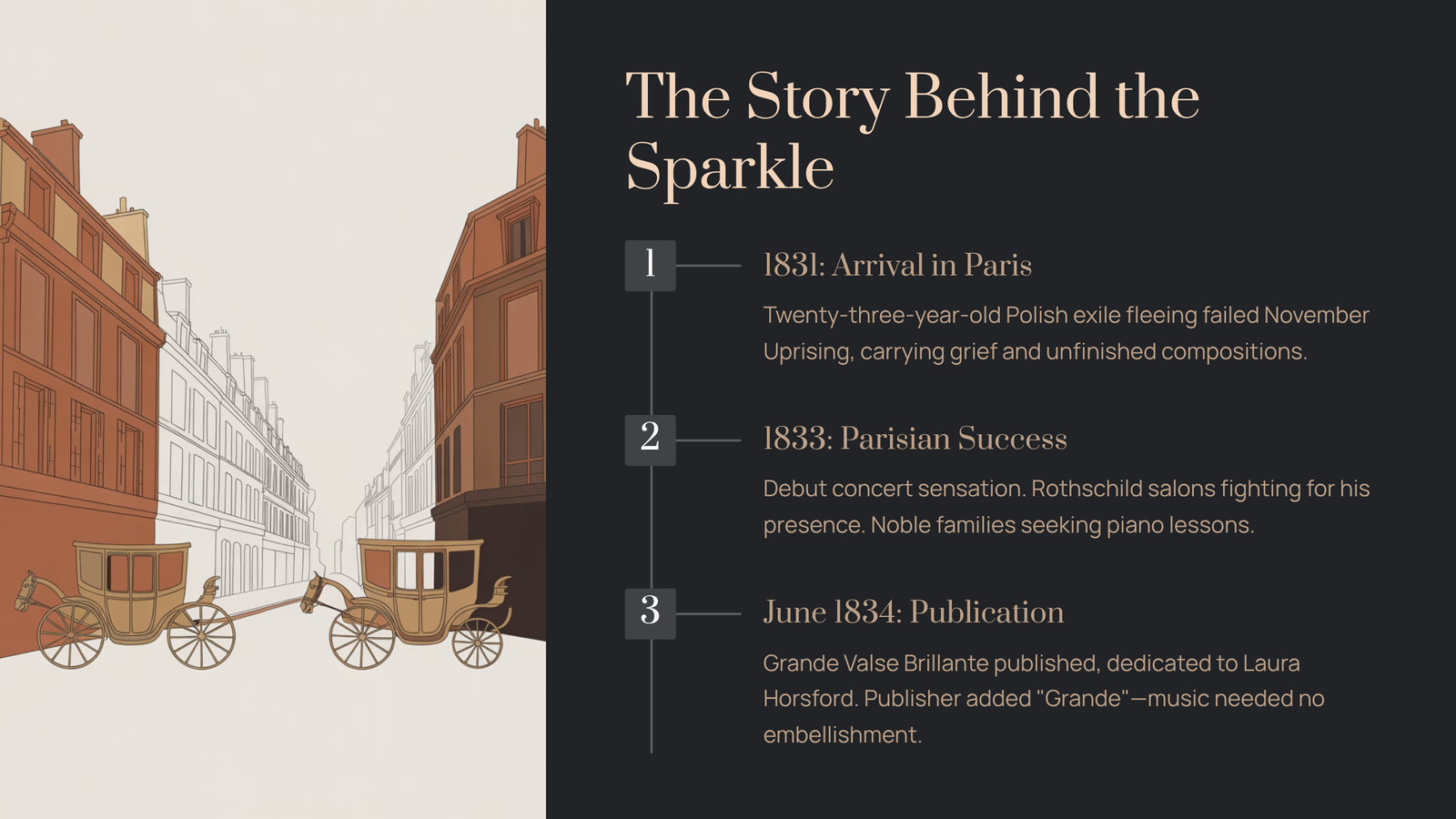

The Story Behind the Sparkle

Picture Paris in 1833. A twenty-three-year-old Polish exile has just conquered the most sophisticated musical salons in Europe. Frédéric Chopin arrived in the city two years earlier, fleeing the failed November Uprising that had devastated his homeland. He carried with him grief, homesickness, and a notebook full of unfinished compositions.

But Paris welcomed him with open arms. His debut concert was a sensation, and soon the aristocratic salons of the Rothschild family were fighting for his presence. Young ladies of noble birth lined up for piano lessons. And somewhere in this whirlwind of success, Chopin returned to a waltz he had sketched during his final months in Warsaw.

The Grande Valse Brillante was published in June 1834 with a dedication to Laura Horsford, one of his students and daughter of a British general. Interestingly, the word “Grande” wasn’t Chopin’s idea—his publisher added it, perhaps sensing the commercial appeal of grandeur. But the music itself needed no such embellishment. It was already magnificent.

What Makes This Waltz So Different?

If you’ve ever heard a Viennese waltz—the kind Strauss and Lanner made famous in ballrooms across Europe—you might expect something similar here. You’d be wrong. Chopin himself was almost contemptuous of the dance-hall variety, once writing sarcastically: “Here, waltzes are called works! And Strauss and Lanner, who play them for dancing, are called Kapellmeistern.”

His waltz was never meant for actual dancing. It’s a concert piece, a refined artistic statement dressed in the familiar three-quarter time. The difference is like comparing a tailored Parisian gown to a factory dress—same basic pattern, entirely different universe.

The piece opens not with a gentle invitation to dance, but with a trumpet-like fanfare. Four bars of repeated B-flat notes, building in intensity, literally summon you into an imaginary ballroom. It’s theatrical, almost orchestral in its ambition, despite being written for solo piano.

A Journey Through Seven Dance Themes

One of the most remarkable aspects of this waltz is its structure. Rather than a simple tune repeated with variations, Chopin weaves together seven distinct melodic themes, each with its own character and mood. Think of it as seven different couples at a grand ball, each dancing in their own style.

The main theme arrives after that dramatic opening, climbing earnestly upward through the home key of E-flat major. It’s elegant and straightforward, like the host greeting guests with a warm handshake. Then comes the second theme—marked “leggieramente” (lightly)—a playful, skittering figure of repeated notes in A-flat major. The music literally sparkles here, like candlelight reflecting off crystal chandeliers.

The middle section brings the most dramatic shift. A tender, almost coy melody appears in D-flat major, and suddenly the energetic spinning stops. The music rocks gently instead of whirling. This is the intimate conversation between dances, the moment when partners catch their breath and share a glance.

Then comes the “con anima” section—”with soul”—and Chopin demands something more than technical accuracy. The music darkens slightly as it passes through B-flat minor, wrapped in what one analyst called “sentimental mist.” Grace notes drip like dewdrops from the melody. It’s the emotional heart of the piece, a reminder that even the most glittering party has its moments of reflection.

Your Listening Guide: What to Notice

The Opening Fanfare (0:00-0:20): Listen for the trumpet-call effect. Those insistent repeated notes aren’t just an introduction—they’re a summons. Notice how the tension builds through the crescendo before releasing into the main theme.

The Sparkling Section (around 0:30): When you hear rapid, light repeated notes marked “leggieramente,” pay attention to the contrast between staccato and legato passages. Six crisp, detached notes followed by six smooth, singing ones. It’s like watching a dancer alternate between quick steps and graceful glides.

The Tender Middle (around 1:30-2:30): The key change to D-flat major signals a shift in mood. The music becomes more intimate, more personal. This is where Chopin shows he’s not just a showman but a poet.

The “Con Anima” Passage (around 2:30-3:30): When the minor key appears, don’t mistake it for sadness. It’s more like wistfulness—the kind of beautiful melancholy that makes joy feel more precious.

The Coda (final minute): Here’s where Chopin pulls his masterstroke. Listen for how multiple themes from earlier in the piece suddenly appear together, competing for attention before the main theme finally triumphs. It’s like the grand finale of a fireworks display, every previous color exploding simultaneously.

The Technical Magic Behind the Beauty

You don’t need to understand music theory to enjoy this piece, but knowing a bit about Chopin’s craft deepens the experience. Throughout the waltz, he employs what musicians call “hemiola”—a rhythmic trick where two bars of three-beat waltz time are regrouped into three groups of two beats. Your ear senses something is off without quite knowing why. It creates a subtle tension that keeps the music from ever feeling predictable.

Chopin also uses chromatic voice leading, meaning the bass notes move in small, smooth steps rather than large jumps. This creates a sense of continuous flow, like water finding its path downhill. Combined with his generous use of the sustain pedal (essential for that characteristic Chopin “glow”), the harmony seems to shimmer rather than simply change.

Recommended Recordings

Dinu Lipatti: If you listen to only one recording, make it this one. The Romanian pianist, who died tragically young at 33, left behind what many consider the definitive interpretation. His 1948 London performance has remained in print for over 75 years—a testament to its timeless quality. The playing is crystalline, elegant, and utterly natural.

Arthur Rubinstein: The most famous Chopin interpreter of the 20th century brings structural clarity and old-fashioned charm. Some find his approach slightly reserved in the lyrical sections, but his aristocratic poise perfectly captures that “only for countesses” spirit.

Valentina Lisitsa: For a modern interpretation, Lisitsa offers a slightly more moderate tempo that allows the harmonic richness to breathe. Her recording demonstrates how the piece can feel cheerful and elegant without becoming a blur of notes.

Alfred Cortot: If you can forgive occasional wrong notes (and there are more than a few), Cortot’s poetic interpretation remains a gold standard for Romantic expression. He plays as if improvising the music in the moment.

A Second Life on the Ballet Stage

The Grande Valse Brillante found unexpected immortality in 1909 when it became the finale of “Les Sylphides,” a plotless ballet choreographed by Michel Fokine. Set entirely to Chopin’s music (orchestrated by various composers over the years), the ballet uses Op. 18 as its climactic moment—white-clad sylphs and a poet figure whirling together in romantic ecstasy.

This ballet connection has kept the waltz in the public consciousness for over a century. Even if you’ve never heard the piano original, you may have encountered it in orchestral form, with the trumpet fanfare now played by actual trumpets and the sparkling repeated notes dancing between woodwinds and strings.

Why This Piece Still Matters

In an era when waltzes were churned out by the dozens for commercial consumption, Chopin created something that transcended its humble dance origins. The Grande Valse Brillante isn’t really about dancing at all. It’s about the idea of dancing—the elegance, the romance, the fleeting joy of movement and music intertwined.

Chopin took a populist form and made it aristocratic. He took three-quarter time and filled it with poetry. He took a five-minute piece and gave it the emotional range of a symphony. And he did it all while making it sound effortless, as if this music simply fell from his fingers onto the keyboard.

That’s why, nearly two centuries later, we’re still listening. That’s why pianists from amateurs to virtuosos keep this piece in their repertoire. And that’s why Chopin’s dismissive “only for countesses” feels less like snobbery and more like prophecy. This music elevates everyone who hears it to the aristocracy of the heart.

The next time you listen, close your eyes and imagine that Parisian salon—candlelit, perfumed, filled with the cream of European society. Then remember that the same magic is available to you, wherever you are, whenever you press play. That’s the true brilliance of the Grande Valse Brillante.