📑 Table of Contents

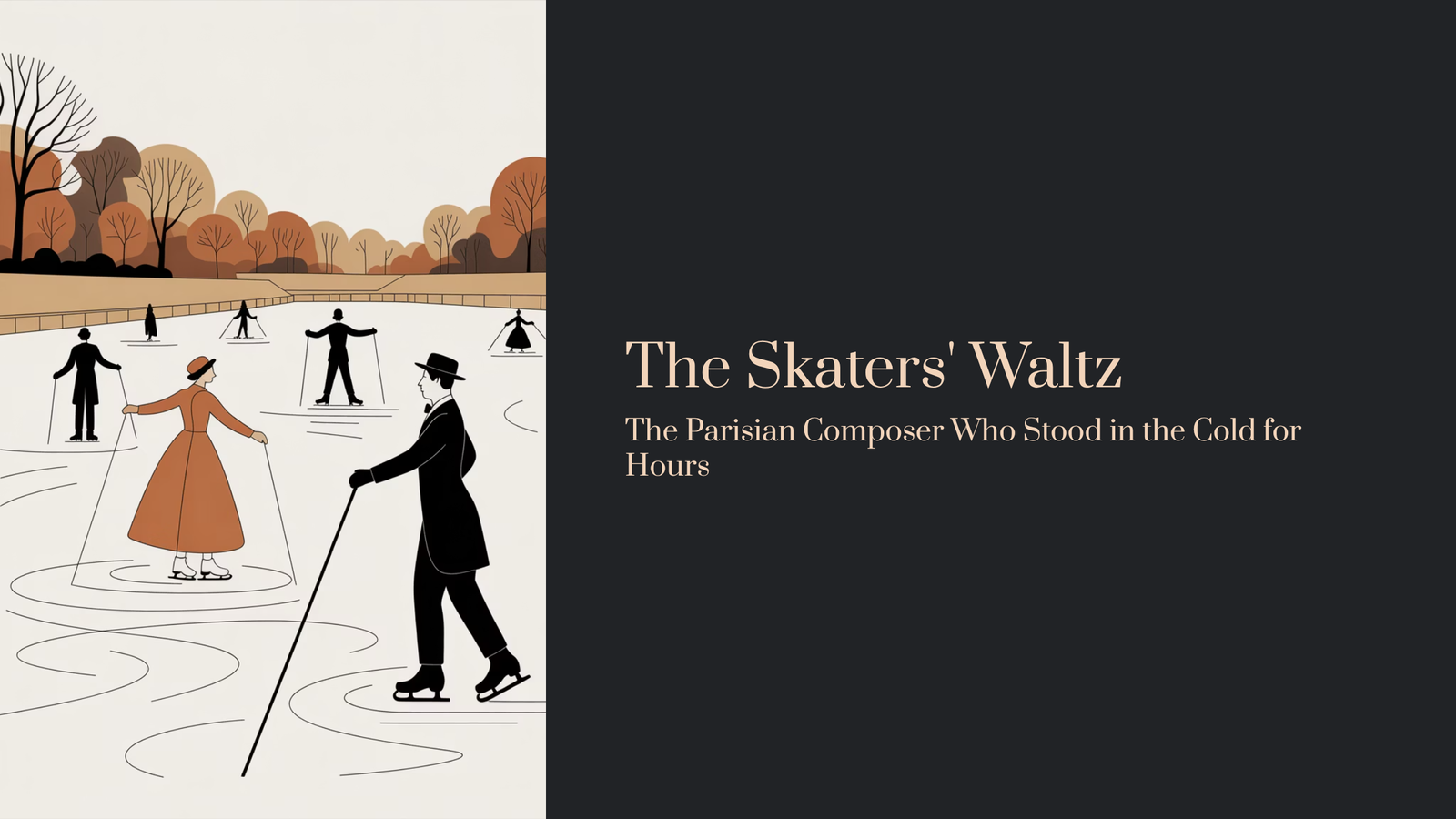

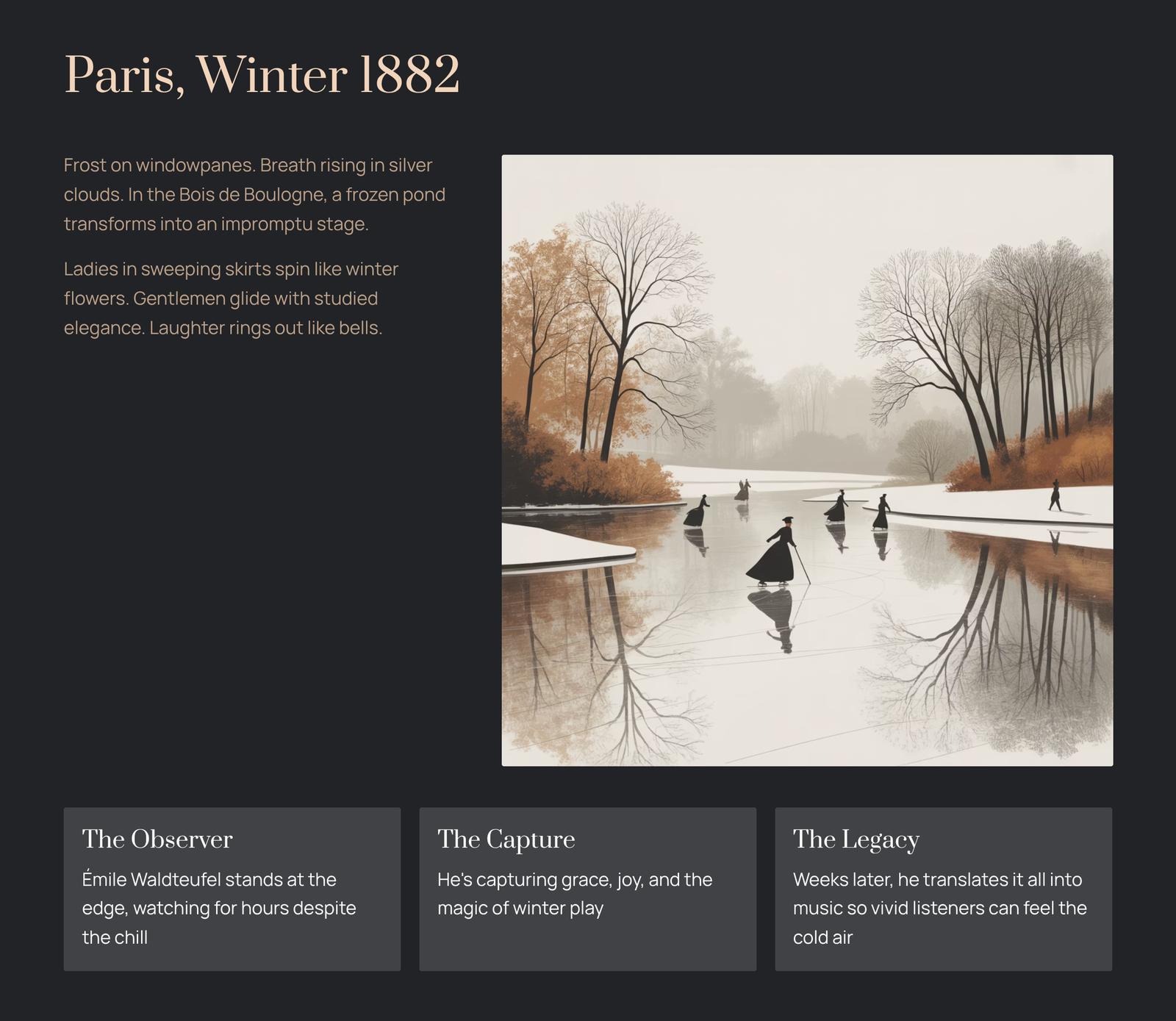

Close your eyes for a moment and imagine Paris in the winter of 1882. Frost paints delicate patterns on windowpanes, breath rises in silver clouds, and in the Bois de Boulogne—that sprawling park beloved by Parisians—a frozen pond has transformed into an impromptu stage. Ladies in sweeping skirts spin like winter flowers. Gentlemen glide with studied elegance. Laughter rings out against the cold air like bells.

Standing at the edge of this scene, watching for hours despite the chill, is a middle-aged composer named Émile Waldteufel. He’s not just passing time. He’s capturing something—the grace of human movement, the joy of winter, the particular magic that happens when people forget themselves and simply play. Weeks later, he would translate everything he witnessed into music so vivid that listeners, even now, can feel the cold air on their cheeks.

That music became “The Skaters’ Waltz,” and there’s a good chance you’ve heard it without knowing its name.

The “French Waltz King” You’ve Never Heard Of

Here’s an odd thing about classical music: some of the most famous pieces were written by composers whose names have faded into obscurity. Waldteufel is a perfect example. His “Skaters’ Waltz” has been featured in everything from Downton Abbey to the 1983 video game Antarctic Adventure, yet most people couldn’t tell you anything about the man himself.

Émile Waldteufel was born in 1837 in Strasbourg, in the Alsace region straddling France and Germany. Music ran in his blood—his father conducted orchestras, his brother played violin professionally, and his mother had once studied with students of Haydn himself. By the time he composed “The Skaters’ Waltz,” Waldteufel had already served as the official dance music director for Emperor Napoleon III and was performing regularly at Buckingham Palace for Queen Victoria.

While Johann Strauss II dominated Vienna as the “Waltz King,” Waldteufel carved out his own territory as the “French Waltz King.” The difference between them wasn’t just geography. Strauss’s waltzes are robust and hearty, like a Viennese coffeehouse filled with spirited conversation. Waldteufel’s work is more like a Parisian salon—subtle, romantic, laced with delicate perfume. His harmonies are softer, his melodies more dreamlike, his overall effect more intimate.

In 1882, at the peak of his creative powers, Waldteufel visited the Cercle des Patineurs—an exclusive skating rink in the Bois de Boulogne where Paris’s elite gathered each winter. What he saw there would become his most enduring legacy.

What the Music Actually Sounds Like

“The Skaters’ Waltz” opens with French horns playing a warm, pastoral melody—imagine the moment before the first skater steps onto the ice, that breath of anticipation. Then comes the magic: quick, gliding phrases that seem to sweep across the orchestra like blades across a frozen surface.

The piece follows the traditional Viennese waltz structure, with an introduction followed by four distinct waltz sections, a brilliant cadenza, and a satisfying coda. But Waldteufel uses this familiar framework to paint an entire winter afternoon.

The first waltz introduces the main theme—a broad, singing melody carried by violins that captures the elegant glide of experienced skaters moving in long, graceful curves. Listen for how the cellos and basses provide that characteristic “oom-cha-cha” waltz rhythm underneath, creating the sensation of effortless movement over solid ice.

The second waltz brings more energy. The melody starts leaping upward in bold intervals, mimicking the way a confident skater might launch into a spin or a small jump. Trumpets and horns add brightness, almost like a fanfare celebrating a particularly dazzling move.

Then comes the third waltz—a moment of respite. The music grows more lyrical and tender, as if our skaters have slowed to catch their breath or perhaps to simply enjoy the beauty around them. This is winter not as harsh adversary, but as gentle backdrop.

The fourth waltz is the shortest and most dreamlike, floating by almost like a whispered memory. And then the cadenza arrives: a brilliant, show-stopping passage where the orchestra demonstrates its full virtuosity, all those swirling scales and rapid passages conjuring images of skaters in their final, most daring performances of the day.

The piece ends where it began, with the main theme returning in triumph before a satisfying final cadence—the musical equivalent of skaters taking their final bows as the sun begins to set.

The Secret Ingredient: Sleigh Bells

Here’s something to listen for that many people miss: throughout “The Skaters’ Waltz,” Waldteufel weaves in the gentle shimmer of sleigh bells. It’s such a subtle touch that you might not consciously notice it, but it transforms the entire atmosphere. Those bells don’t just suggest winter—they place you physically in that cold, crisp air. They’re the sonic equivalent of seeing your breath fog in front of you.

Waldteufel was a master of these small orchestral details. Where a lesser composer might have simply written a pleasant tune, he created a complete sensory experience. The pizzicato (plucked) strings evoke the sharp click of skate blades. The harp glissandos shimmer like light reflecting off ice. Every choice serves the central image.

Why This Piece Refuses to Die

“The Skaters’ Waltz” achieved immediate success upon its publication in 1882, and it has never really gone away. Part of this longevity comes from its sheer craftsmanship—the melodies are genuinely beautiful, memorable without being simplistic. But there’s something more.

This music captures a particular human experience that transcends its era: the pure joy of play. Skating on frozen ponds was, in Waldteufel’s time, one of the few activities where social barriers somewhat relaxed. On the ice, what mattered was grace, not status. The music reflects this—it’s elegant but never stuffy, refined but genuinely fun.

The piece has appeared in films ranging from the 1929 Hollywood Revue to 2019’s Rocketman, where a young Elton John is shown picking out the melody on piano—his first spark of musical genius. It soundtracked Lady Rose’s coming-out ball in Downton Abbey. For millions of gamers, it’s inseparable from memories of guiding a penguin across Antarctic ice in Konami’s classic Antarctic Adventure.

Each generation discovers it anew and finds it still works. That’s the mark of music that touches something universal.

How to Really Listen

If you’re encountering “The Skaters’ Waltz” with fresh ears, here are a few ways to deepen your experience.

First, try listening with the imagery in mind. Don’t think of this as abstract music—picture actual people on actual ice. Notice how each section seems to capture different moments: the anticipation before stepping onto the rink, the first tentative glides, the growing confidence, the dazzling tricks, the peaceful moments of simply enjoying the sensation of movement.

Second, pay attention to the contrast between the sections. Waldteufel wasn’t just stringing pretty tunes together; he was structuring an emotional journey. The energetic second waltz means more because it follows the graceful first. The tender third waltz provides relief before the virtuosic display to come.

Third, notice the sleigh bells and ask yourself: what do they add? Would the piece feel the same without them? This kind of active listening—asking yourself questions about compositional choices—transforms passive hearing into genuine engagement with the music.

Recommended Recordings

For your first encounter, Herbert von Karajan’s recordings with the Berlin Philharmonic or Philharmonia Orchestra offer pristine clarity and elegant phrasing. Karajan brings out the aristocratic beauty of the piece, treating it with the same seriousness he’d give to a Beethoven symphony.

For something more theatrical and warm, André Rieu’s performances with his Johann Strauss Orchestra emphasize the fun and spectacle. Rieu understands that this is, at its heart, entertainment music—meant to bring smiles, meant to make you want to dance.

Both approaches are valid, and listening to both will show you how much interpretation matters even in music this seemingly straightforward.

A Composer Watching Skaters

What strikes me most about the origin story of “The Skaters’ Waltz” is the image of Waldteufel standing in the cold, watching people have fun, and deciding that what he saw was worth immortalizing in music.

He wasn’t documenting a historic event or expressing tortured inner feelings. He was simply paying attention to a beautiful ordinary scene and saying: this matters. This deserves to be remembered. The joy of strangers gliding across ice on a winter afternoon. The way light plays on frozen surfaces. The laughter, the motion, the cold air turning breath to mist.

That’s what you’re hearing when you listen to “The Skaters’ Waltz”—a moment of ordinary magic, carefully preserved in sound, waiting for anyone who wants to step into it. All these years later, the ice is still there. The skaters are still gliding. And if you close your eyes, you might just feel the chill of a Parisian winter brushing against your cheek.