📑 Table of Contents

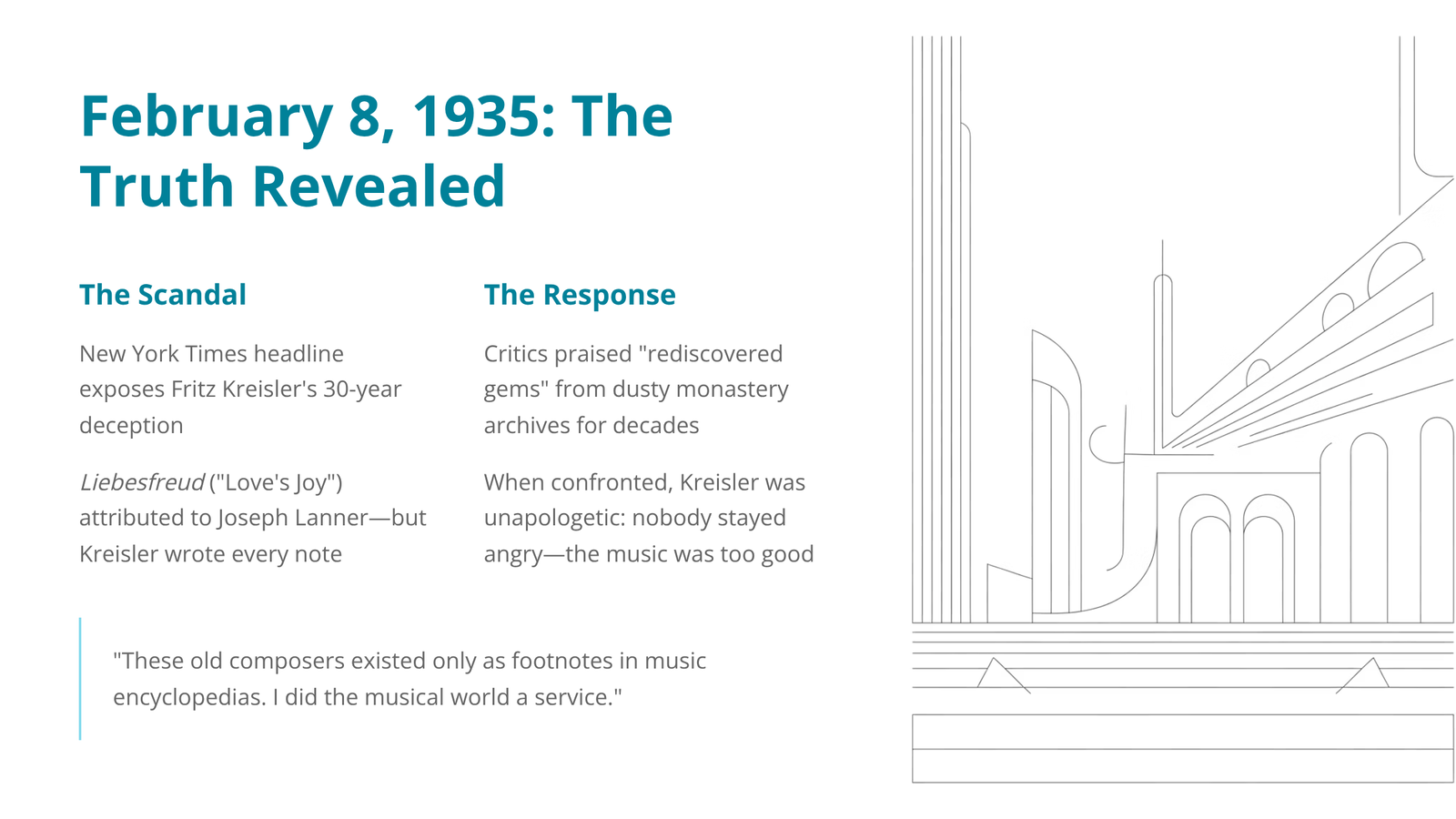

Imagine waking up on February 8, 1935, unfolding your copy of the New York Times, and reading this headline: a beloved violinist had been fooling the entire classical music world for thirty years.

That violinist was Fritz Kreisler. And the piece at the center of this delightful scandal? A sparkling little waltz called Liebesfreud—German for “Love’s Joy.”

For three decades, critics had praised this piece as a rediscovered gem from Joseph Lanner, an obscure 19th-century Viennese dance composer. They marveled at Kreisler’s generosity in unearthing such treasures from dusty monastery archives. They wrote glowing reviews about how perfectly Kreisler performed these “antique” works alongside his own compositions.

There was just one problem: Kreisler had written every note himself.

When confronted, his response was wonderfully unapologetic. These old composers, he argued, existed only as footnotes in music encyclopedias. Their authenticated works were rotting in forgotten libraries. He had done the musical world a service.

And here’s the truly remarkable part: nobody stayed angry for long. The music was simply too good.

The Man Behind the Mischief

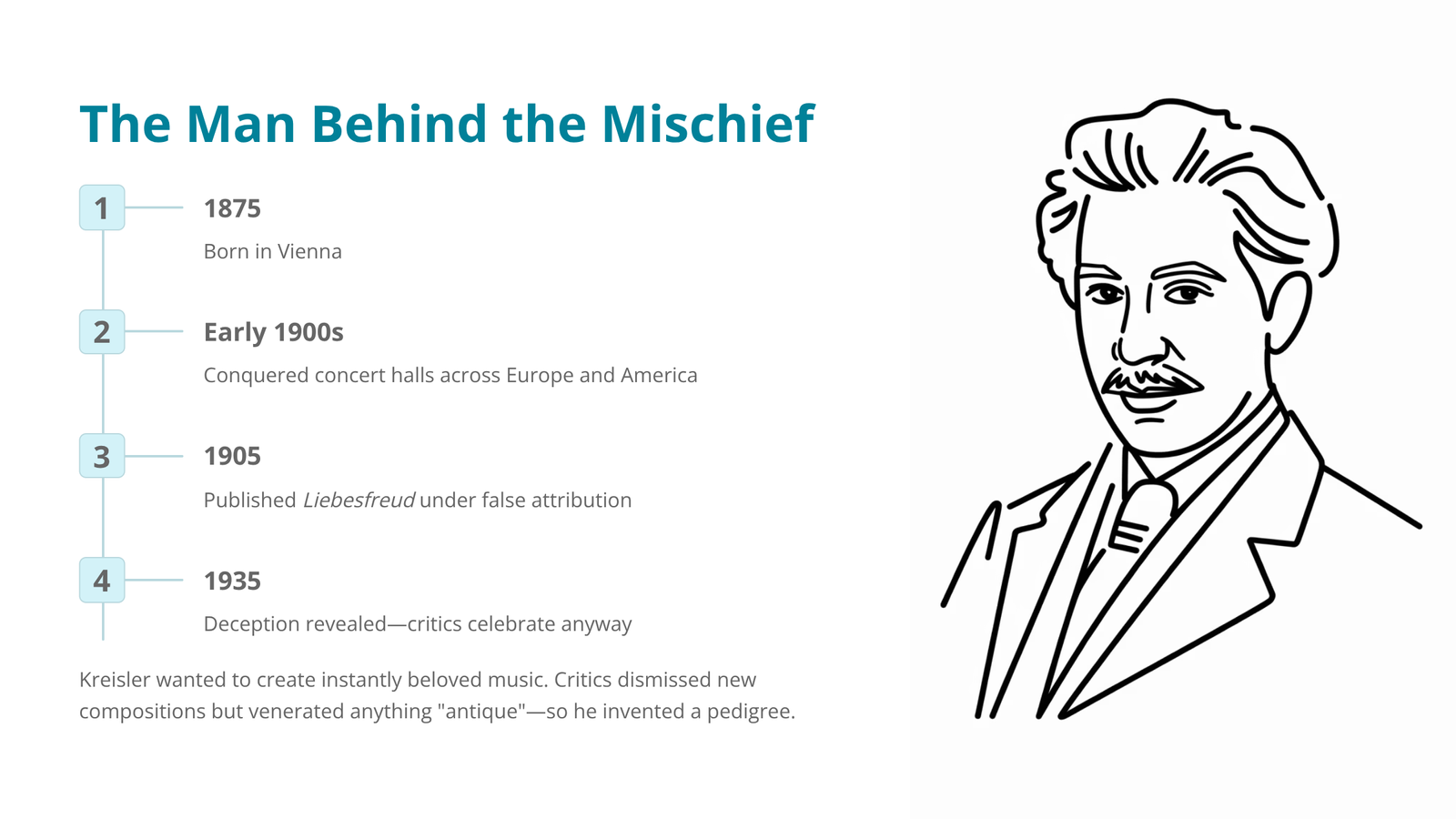

Fritz Kreisler was born in Vienna in 1875 and became one of the most celebrated violinists of the early twentieth century. By 1905, when he published Liebesfreud, he had already conquered concert halls across Europe and America. He had debuted with the Berlin Philharmonic, dazzled London audiences, and married Harriet Lies, a Vassar-educated American who brought stability to his restless artistic life.

But Kreisler wasn’t content being merely a performer. He wanted to create music that audiences would love instantly—pieces that could end a concert on a note of pure joy. The problem? Critics often dismissed new compositions while venerating anything with an “antique” pedigree.

So Kreisler invented one.

He attributed Liebesfreud and its companion pieces to Joseph Lanner, a real but largely forgotten composer of Viennese dance music. The deception worked perfectly. Critics who might have dismissed “another Kreisler encore piece” instead celebrated the “rediscovery” of a Viennese master.

The joke, it turned out, was on them.

What Makes This Waltz So Irresistible

Liebesfreud belongs to a set of three pieces Kreisler called Alt-Wiener Tanzweisen (Old Viennese Dances). While its sibling Liebesleid (Love’s Sorrow) dwells in melancholy, Liebesfreud is pure effervescence.

The piece draws from the Ländler tradition—those folk dances from the Austrian Alps that eventually evolved into the sophisticated Viennese waltz. But Kreisler wasn’t interested in museum-piece authenticity. He wanted to capture something more elusive: the spirit of pre-war Vienna, that golden era of elegant ballrooms and champagne-lit evenings that would soon vanish forever.

Written in bright C major with a spirited Allegro tempo, the music practically dances off the page. The violin opens with sparkling arpeggios over the piano’s rhythmic foundation, immediately establishing the atmosphere of a festive salon. Throughout the piece, Kreisler employs a technique called “double-stopping”—playing two strings simultaneously—which gives the violin a richer, almost orchestral sound.

One of the most clever touches involves rhythm. Kreisler frequently uses “hemiola,” a technique where the expected three-beat waltz pattern temporarily feels like it’s in two. This creates a playful tug-of-war between the violin and piano, as if two dancers are gently teasing each other on the ballroom floor.

A Listening Journey Through Love’s Joy

When you press play on Liebesfreud, here’s what to listen for:

The Opening Flourish: The piece announces itself with confident, ascending arpeggios. Notice how the piano establishes a steady pulse while the violin immediately starts showing off. This isn’t shy music—it wants your attention.

The Main Theme: After the introduction, a memorable melody emerges. Pay attention to how it seems to bounce slightly on each beat, like a dancer who can’t quite stay still. The short rests Kreisler writes into the melody act as springboards, propelling the music forward.

The Conversation Begins: About a third of the way through, something subtle but important happens. The piano stops being merely accompaniment and starts answering the violin with its own melodic ideas. Listen for moments where the two instruments seem to be responding to each other, like friends completing each other’s sentences.

A Brief Journey Elsewhere: The middle section shifts to F major—a warmer, slightly softer key. The mood becomes more nostalgic, almost wistful. Some listeners hear this as a moment of reflection amid the celebration, like pausing at a party to remember someone who couldn’t be there.

The Grand Return: The original theme comes back, now feeling like an old friend. But Kreisler doesn’t let things get too comfortable. The piano rises to its higher register, playing crisp chords that sound almost orchestral—like brass instruments joining a small ensemble.

The Joyful Ending: The piece concludes by returning to its opening material, bringing the dance full circle. The final cadence is decisive and satisfying, like the last step of a perfectly executed waltz.

The Kreisler Sound

Part of what makes historical recordings of Liebesfreud so captivating is Kreisler’s revolutionary playing style. Before him, violinists used vibrato sparingly, saving it for especially expressive moments. Kreisler used it constantly, even in fast passages, giving his sound an unprecedented warmth and intensity.

He also employed generous portamento—those sliding connections between notes that can sound either unbearably cheesy or heartbreakingly beautiful depending on who’s playing. In Kreisler’s hands, these slides became a signature, transporting listeners straight to the heart of old Vienna.

When you hear modern violinists perform this piece, notice how each one navigates this legacy. Some embrace the old-fashioned sentimentality. Others take a more restrained approach, letting the composition’s structure speak for itself.

Recordings Worth Your Time

Fritz Kreisler himself (1938, with pianist Franz Rupp) remains the essential recording. His sparkling bow technique and perfect sense of Viennese timing set the standard that all others must contend with.

Leonid Kogan brings the depth of the Soviet violin school to a piece that might seem too “light” for such serious treatment. The result is surprisingly moving.

Barnabás Kelemen with pianist Zoltán Kocsis offers a modern perspective that strips away some of the traditional sentimentality. Their interpretation has an angular, almost Bartókian bite that reveals new dimensions in the music.

For pianists, Sergei Rachmaninoff’s solo transcription (1925) transforms the salon piece into something approaching a virtuoso showpiece. He added an improvisatory prelude and brilliant pianistic flourishes that put his own stamp on Kreisler’s creation.

The Joy That Outlasted an Era

There’s a bittersweet footnote to Liebesfreud that becomes apparent when you know Kreisler’s biography. In 1914, at age thirty-nine, he was conscripted into the Austrian army and sent to the Eastern Front. He served for barely a month before being wounded and discharged, but the experience changed him forever.

After the war, these pieces took on new meaning. They were no longer just entertainment—they had become musical time capsules of a world that no longer existed. Kreisler himself later described them as “the last vestiges of pre-war Vienna.”

So when you listen to Liebesfreud today, you’re hearing something more complex than simple joy. You’re hearing a memory of joy, preserved in amber by a man who understood that some things become more precious precisely because they cannot last.

The critics Kreisler fooled for thirty years were, in a sense, right all along. These pieces did come from another era. They just happened to be written by a time traveler who could see where history was heading—and wanted to save something beautiful before it disappeared.

That’s the real magic of Liebesfreud. It’s not just love’s joy. It’s joy itself, caught at the moment before it learned what sorrow was.