📑 Table of Contents

Here’s something strange: Mozart never called this piece “Elvira Madigan.” He simply finished it on March 9, 1785, performed it the very next day in Vienna, and moved on to his next project. For nearly two centuries, it was just Piano Concerto No. 21 in C Major, K. 467.

Then came 1967. Swedish filmmaker Bo Widerberg needed music for his movie about Elvira Madigan—a real Danish circus performer who fell in love with a married Swedish cavalry officer in the 1880s. Their forbidden romance ended in tragedy. Widerberg chose Mozart’s second movement, and suddenly this 18th-century composition had a name, a face, and a heartbreaking story attached to it forever.

The nickname stuck because the music itself seems to understand something about love and loss that words cannot capture.

What Mozart Was Doing When He Wrote This

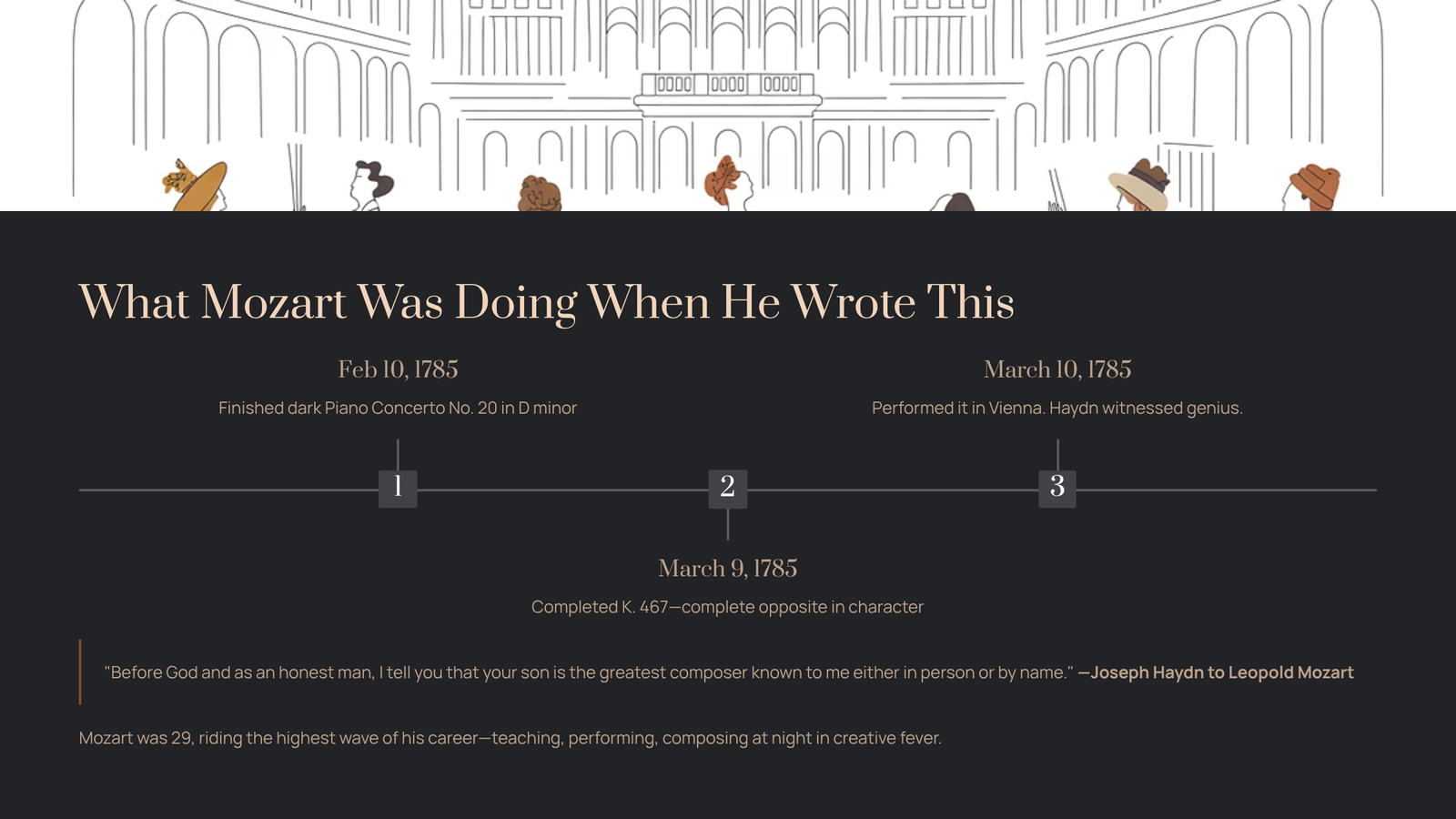

Picture Vienna in early 1785. Mozart was 29 years old and riding the highest wave of his career. He had just finished his stormy Piano Concerto No. 20 in D minor—a dark, turbulent work—on February 10. Exactly four weeks later, he completed this concerto, its complete opposite in character.

His father Leopold visited that month and witnessed the chaos firsthand. Mozart was giving subscription concerts every Friday, teaching piano lessons daily, composing at night, and performing his own works. Leopold wrote home describing how music copyists were still frantically copying parts while audiences waited.

The day after Mozart finished this concerto, Joseph Haydn visited his apartment. After hearing some of Mozart’s recent work, Haydn turned to Leopold and said something remarkable: “Before God and as an honest man, I tell you that your son is the greatest composer known to me either in person or by name.”

This was the atmosphere surrounding the birth of K. 467—creative fever, artistic triumph, and the recognition of genius.

Why the Second Movement Feels Like a Dream

The Andante opens with something unusual for its time: muted strings. Mozart instructed his violinists to play “con sordino”—with mutes attached to their instruments. This softens the sound, making it almost ghostly.

Underneath the melody, cellos and basses play pizzicato—plucking their strings instead of bowing them. Meanwhile, second violins and violas maintain a gentle triplet pattern, like a quiet heartbeat that never stops. This combination creates what one musicologist called a “magical spell.”

The main melody unfolds over 21 measures in a carefully asymmetrical pattern: three measures, then three more, then two, then two, then a breathless five-measure phrase broken into individual beats, before returning to stability with three-plus-three. Mozart makes calculated structure sound like spontaneous emotion.

The Hidden Sadness Beneath the Beauty

Listen carefully and you’ll notice something unsettling. The melody makes unusually large leaps—sometimes plunging more than two octaves. These dramatic drops interrupt the serenity, suggesting restlessness beneath the calm surface.

Mozart also moves through unexpected key changes. The movement is in F major, but it wanders into F minor, C minor, G minor, and eventually reaches A-flat major—a distant harmonic territory that feels like entering a completely different emotional world. Around the four-minute mark, the triplet accompaniment suddenly stops, exposing this modulation like a wound.

Critics have described the movement as “bittersweet,” “rapturous,” and possessing “great profundity.” It sounds beautiful on first listen, but repeated hearings reveal layers of melancholy that the surface elegance initially conceals.

How to Listen: A Simple Guide

First listen (just feel it): Don’t analyze anything. Put on headphones, close your eyes, and let the music wash over you. Notice how it makes you feel physically—does your breathing slow? Do your shoulders relax?

Second listen (notice the texture): Focus on the plucked bass notes that anchor each phrase. Then shift your attention to the constant triplet rhythm in the middle voices. Finally, follow the main melody floating above everything.

Third listen (track the emotional journey): The piece moves from peaceful introduction to piano entry, through increasingly unstable key changes, reaches a peak of tension in the middle section, then gradually finds its way back to calm resolution.

The whole movement lasts about seven minutes in most performances—the perfect length for a meditation break or a moment of reflection.

Recommended Recordings to Start With

For the classic romantic interpretation: Géza Anda with the Salzburg Camerata Academica. This is actually the recording used in the 1967 film. It takes a slower tempo that emphasizes the dreamy quality.

For historical accuracy: Ronald Brautigam or Jean-Efflam Bavouzet, both of whom aim for what Mozart might have intended—a genuine walking pace “Andante” rather than the ultra-slow readings that became popular later.

For modern polish: Murray Perahia with the English Chamber Orchestra brings crystalline clarity and emotional intelligence without excessive sentimentality.

Each pianist reveals different aspects of the music. Anda makes you weep; Bavouzet makes you think; Perahia does both.

The James Bond Connection

Here’s a piece of trivia that surprises many classical fans: this movement appears in a James Bond film. In “The Spy Who Loved Me” (1977), the villain Stromberg listens to Mozart’s Andante as his underwater base rises from the ocean. The contrast between the serene music and the megalomaniac’s scheme creates an unsettling effect—beauty in service of destruction.

Mozart’s music has appeared in countless films, but its use in both a tragic Swedish art film and a bombastic spy thriller shows its remarkable adaptability.

What Makes This Movement Timeless

Mozart wrote this piece for a benefit concert—essentially to make money. He probably never imagined people would still be listening 240 years later, let alone associating it with a circus performer who wouldn’t be born for another 82 years.

Yet the music transcends its origins. It captures something universal about human longing: the ache of beauty that cannot last, the tenderness we feel for things we know we’ll lose, the way joy and sorrow can occupy the same moment.

Whether you’re hearing it for the first time or the hundredth, Mozart’s Andante offers a few minutes of refuge from the noise of daily life. It asks nothing of you except stillness and attention. In return, it offers something close to grace.