📑 Table of Contents

There’s a moment in this piece—around thirty seconds in—where the oboe holds a single note so long that time itself seems to stop. The first time I heard it, I didn’t know anything about Bach’s life when he wrote it. I just knew something felt heavy. Something felt true.

Then I learned the story behind it, and I understood why.

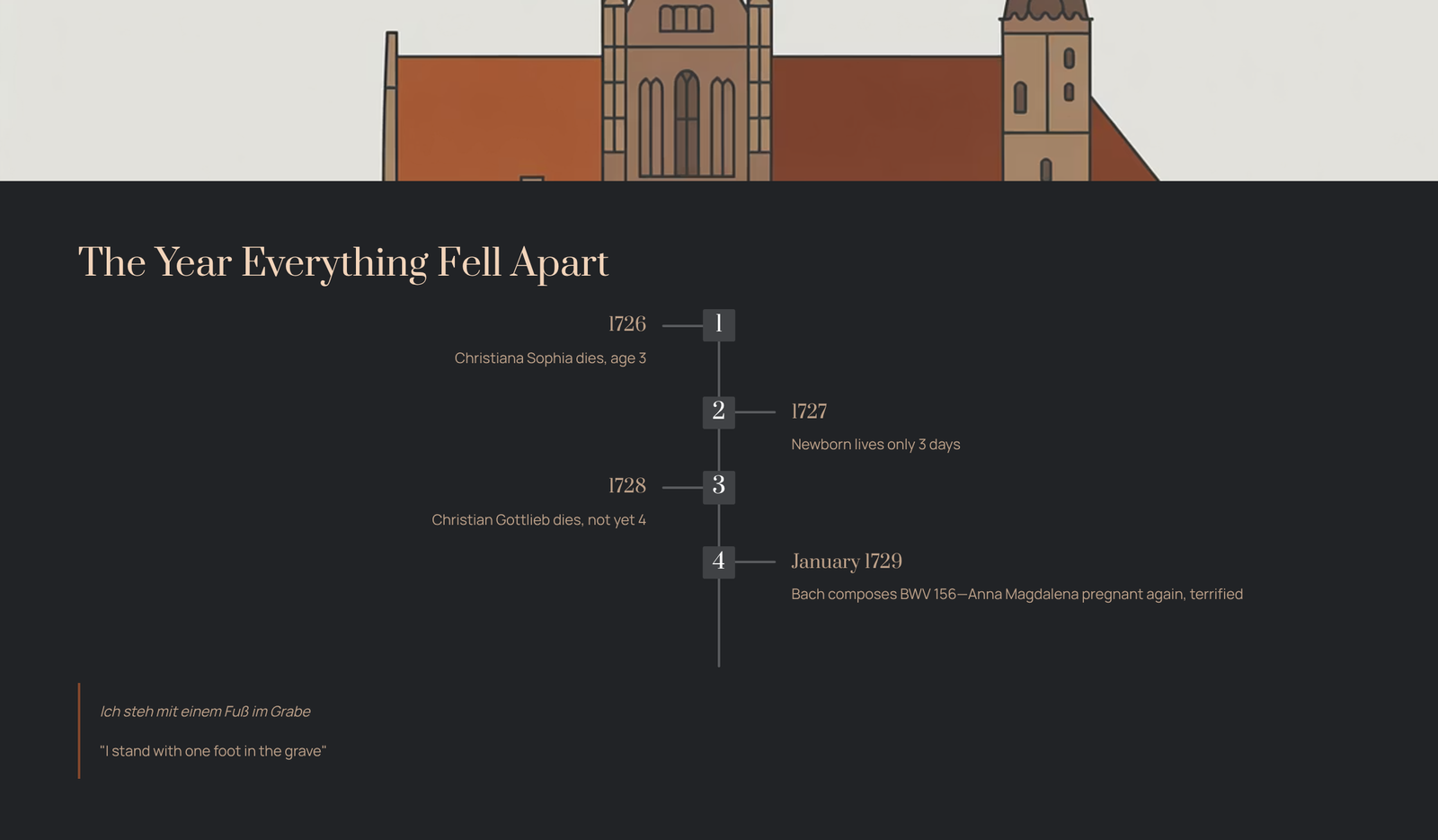

The Year Everything Fell Apart

In the late 1720s, Johann Sebastian Bach was at the height of his career. As the music director at Leipzig’s most prestigious churches, he was composing at a furious pace, churning out cantatas week after week. But behind the scenes, his household was falling apart.

Between 1726 and 1728, Bach and his wife Anna Magdalena buried three children in rapid succession. First, their daughter Christiana Sophia, just three years old. Then a newborn who lived only three days. Then Christian Gottlieb, not yet four. When Bach sat down to compose Cantata BWV 156 in January 1729, Anna Magdalena was pregnant again—terrified, grief-stricken, and watching her husband pour his sorrow into music.

The cantata’s title? Ich steh mit einem Fuß im Grabe—”I stand with one foot in the grave.”

This wasn’t abstract theology for Bach. It was his daily reality.

What Makes This Music So Haunting

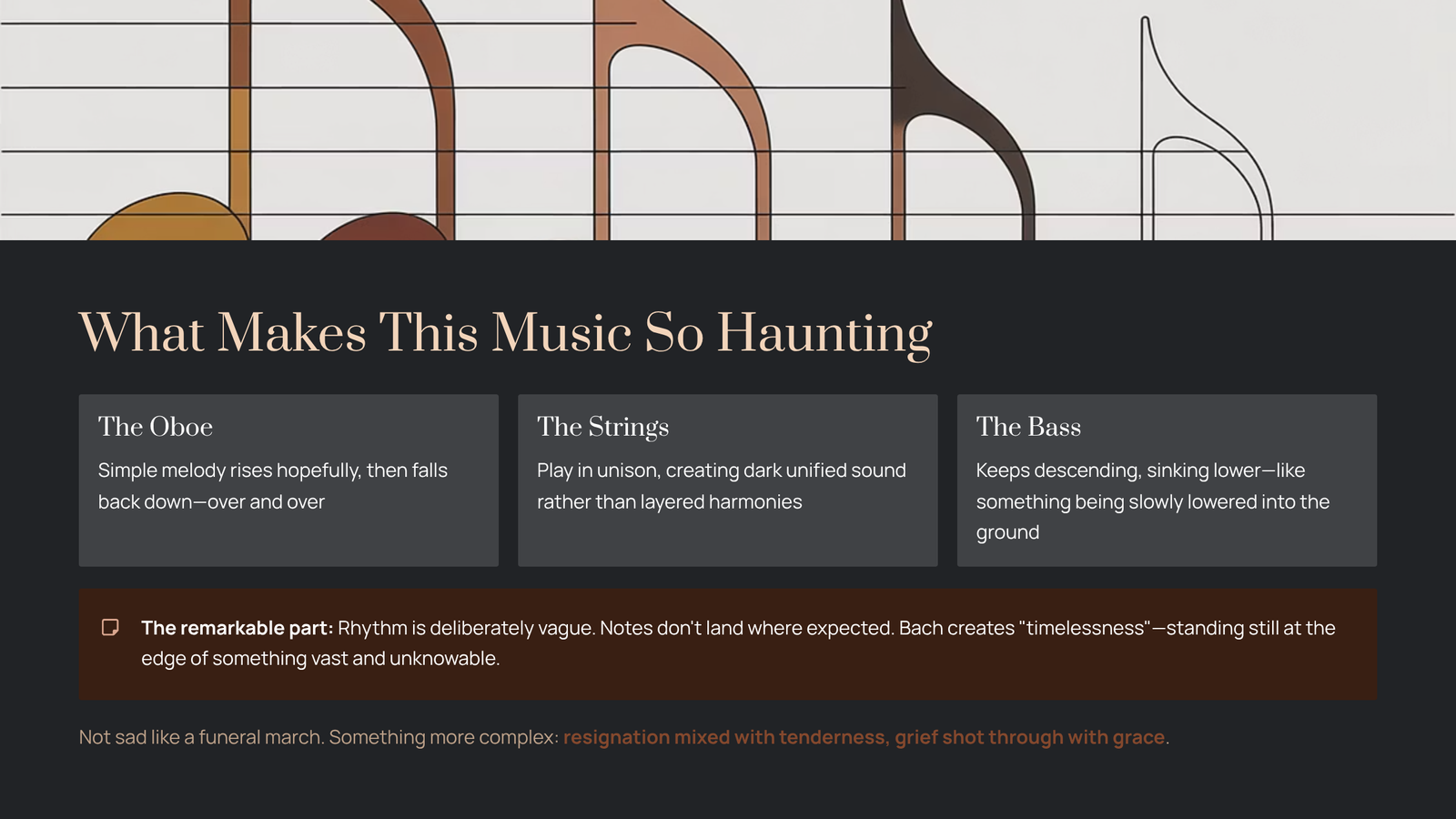

The Arioso (also called Sinfonia) that opens the cantata runs only about three minutes, but it packs an emotional weight far beyond its length. Here’s what’s happening musically, even if you’ve never studied music theory.

The oboe carries the main melody—a simple, singing line that rises hopefully, then falls back down, over and over. Underneath, the strings play together in unison, creating a dark, unified sound rather than the usual layered harmonies. The bass line keeps descending, sinking lower and lower like something being slowly lowered into the ground.

But here’s the remarkable part: the rhythm is deliberately vague. The notes don’t land where you expect them to. There’s no clear pulse driving the music forward. Bach creates what scholars call a sense of “timelessness”—the feeling of standing still at the edge of something vast and unknowable.

It’s not sad in the way a minor-key funeral march is sad. It’s something more complex: resignation mixed with tenderness, grief shot through with grace.

A Listening Guide for First-Timers

If you’re new to classical music, here’s how to approach this piece without feeling lost.

First listen: Just feel it. Don’t try to analyze anything. Put on headphones, close your eyes, and let the music wash over you. Notice where it makes you take a breath. Notice if any moment catches you off guard.

Second listen: Follow the oboe. The oboe is the “voice” of this piece—imagine it as a person singing without words. Listen to how its melody rises with hope, then gently descends. In the second half of the movement, you’ll hear the melody become more decorated, more ornate, as if the singer is adding extra sighs and catches of breath.

Third listen: Feel the weight underneath. Now pay attention to everything below the oboe. The strings move in slow, synchronized waves. The bass keeps sinking. Together, they create a kind of gravitational pull, anchoring all that floating melody to something heavy and earthbound.

The key moment: Around the 1:45 mark (timing varies by recording), the opening melody returns, but now with elaborate ornamental flourishes. It’s the same tune, but transformed—as if someone who was numb with grief has finally found the strength to weep properly.

Why This Piece Still Matters Today

There’s a reason this short movement has been borrowed, arranged, and recorded hundreds of times over three centuries. Woody Allen used it in Hannah and Her Sisters. Leopold Stokowski arranged it for full orchestra. Bach himself recycled the melody into his Harpsichord Concerto in F minor. The music refuses to stay buried.

I think it’s because Bach captured something universal: the experience of standing at the threshold between hope and despair, between life and death, and finding that the threshold itself can be beautiful.

You don’t need to be religious to feel it. You don’t need to have lost a child. You just need to have stood at some edge in your own life—a hospital room, a goodbye, a 3 AM reckoning with your own mortality—and felt the strange calm that sometimes arrives in those moments.

Bach knew that calm. He put it in the music. And three hundred years later, we can still hear it.

Recommended Recordings

If you want to experience this piece at its finest, here are three very different interpretations worth exploring.

For historical authenticity: The Netherlands Bach Society recording, featuring Lars Ulrik Mortensen’s intimate direction. Their “All of Bach” project offers a transparent, period-instrument sound that lets you hear every voice clearly. Available free on YouTube.

For emotional depth: Karl Richter’s recordings from the 1960s bring a weightier, more Romantic approach. The tempos are slower, the colors darker. If you want to feel the gravity of Bach’s grief, this is your recording.

For modern beauty: Lisa Batiashvili’s arrangement for violin, oboe, and orchestra (on Deutsche Grammophon) reimagines the piece for contemporary ears. It’s technically a departure from the original, but it proves how timeless the core melody remains.

A Final Thought

There’s a detail about the original cantata that moves me every time I think about it. In the second movement, a soprano voice enters singing a hymn of faith—”Lord, deal with me according to Your goodness”—while a tenor simultaneously sings about standing at the grave’s edge. The two melodies happen at the same time, completely independent, yet somehow fitting together.

It’s Bach showing us that grief and faith, terror and trust, can coexist in the same moment. Not resolving into each other, not canceling each other out—just existing, together, honestly.

Maybe that’s the real gift of this music. It doesn’t tell you everything will be okay. It just sits with you at the edge and says: I know. I’ve been here too.

Press play. Let the oboe breathe. And give yourself permission to feel whatever comes.