Table of Contents

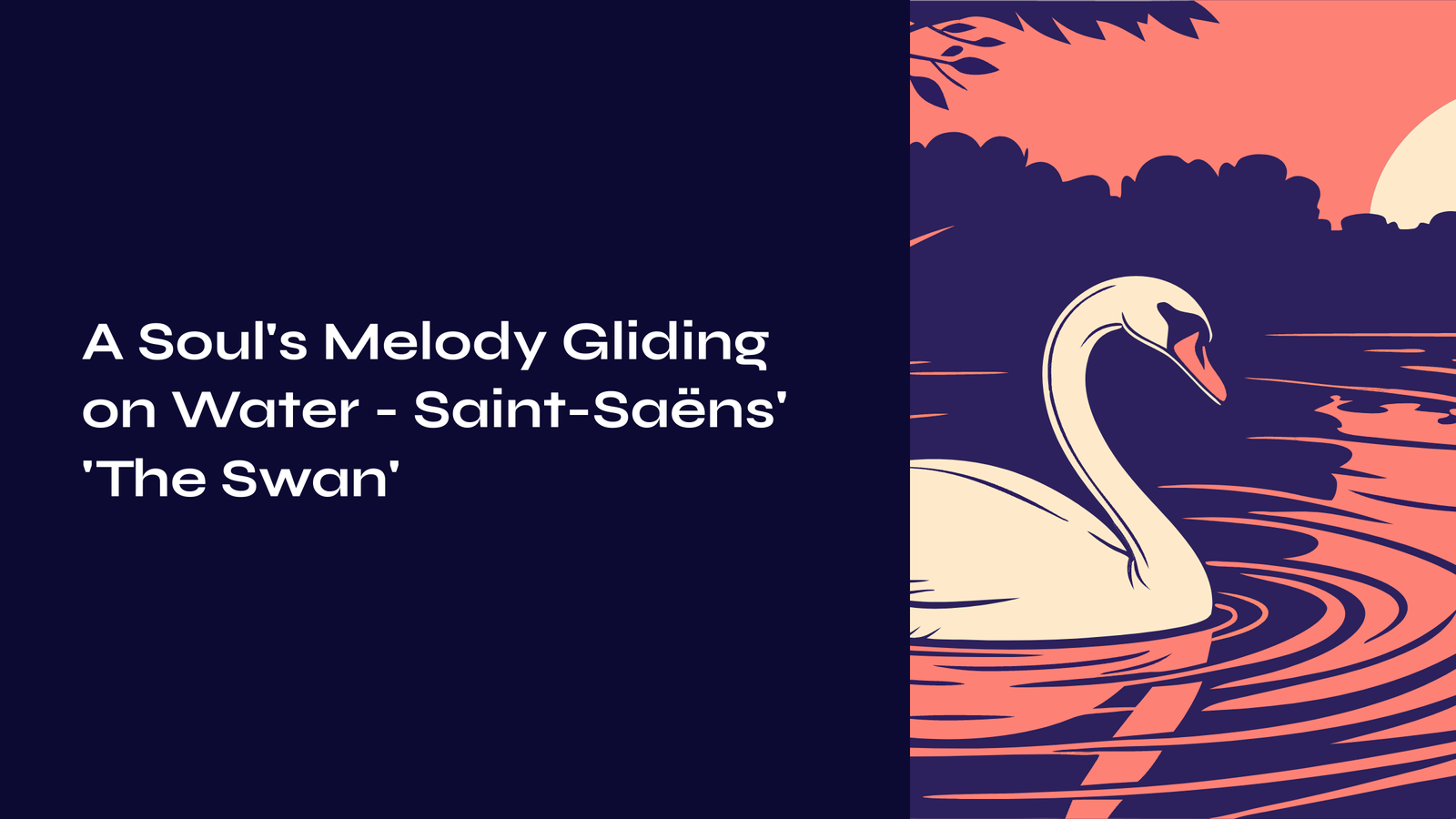

First Encounter on Tranquil Waters

Some music stops time the moment you hear it. Saint-Saëns’ “The Swan” is precisely such a piece. When the cello’s first note cuts through the air, I always conjure the same image: a solitary swan gliding gracefully across a serene lake. That melody, like silver traces drawn upon rippling water, leaves both delicate impressions and profound resonances that seem to hover between audible and ineffable.

Before this brief composition, I am always humbled. Confronted by the depth contained within seemingly simple melodic lines, I’m reminded anew of how powerfully beautiful things can move us. Have you ever experienced such moments while listening to music? Those instances when all the world’s noise fades away, leaving only that single melody to exist in crystalline isolation?

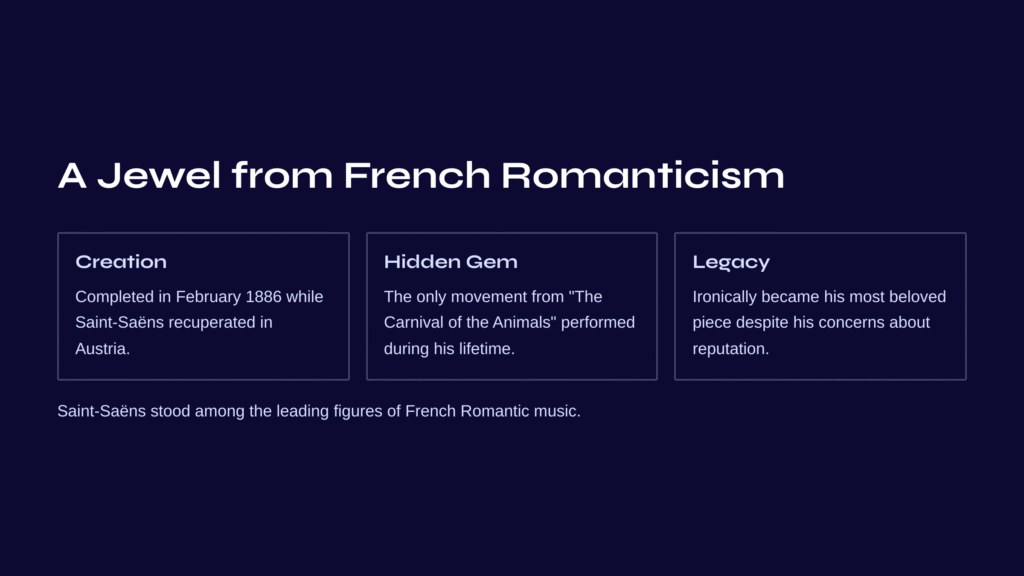

A Jewel from French Romanticism’s Treasury

In February 1886, while recuperating in Austria, Camille Saint-Saëns completed a remarkable work: “The Carnival of the Animals,” a fourteen-movement suite. Concerned that this whimsical composition might damage his reputation as a serious composer, he permitted only one movement—”The Swan”—to be performed publicly during his lifetime. Ironically, from the very work he most guarded, “The Swan” became his most beloved piece.

Saint-Saëns stood among the leading figures of French Romantic music. His musical sensibility, which honored Bach’s traditions while preserving distinctly French elegance, finds its purest expression in “The Swan.” This piece transcends mere animal portraiture to become both a hymn to beauty itself and a meditation on transience.

Melodic Currents Painting Water’s Movement

“The Swan” opens in 6/4 time, marked Andantino grazioso. Above the gentle broken chords created by two pianos, a long cello melody flows like liquid music. These opening measures alone draw us completely into the scene. The piano’s arpeggiated figures suggest water’s movement, while the cello’s singing line traces the swan’s graceful gestures across the surface.

The choice to write the cello part in tenor clef holds special significance. This utilizes the instrument’s most mellifluous register, creating warmth closest to the human voice. The melody unfolds legato, enhanced by portamento and rich vibrato that makes it sound like the swan’s final song upon the water.

In the piece’s middle section, the harmony darkens slightly, building tension. Does this evoke the ancient legend of the swan’s death song? But soon the music returns to bright G major, concluding peacefully in tranquil resignation. The final measures, where the cello ascends to higher registers before fading away, truly evoke a swan taking flight into the distance.

Deep Resonances Within My Heart

Each time I hear this piece, I undergo a curious experience. Though lasting merely two and a half minutes, listening leaves me feeling as though I’ve returned from a long journey. The cello’s melody seems to touch something deep within me. Is it longing? Or perhaps that bittersweet ache that comes from knowing all beautiful things must pass away?

Particularly during the middle section, when the melody briefly darkens, I always ponder the same question: Why must beauty be so ephemeral? Yet simultaneously I realize that perhaps it’s precisely this transience that makes it more precious, more urgently worth cherishing.

While listening to “The Swan,” I often see reflections of myself. Sometimes like the swan gliding gracefully on the surface, sometimes like the same swan paddling frantically beneath the water. That image of appearing serene while constantly moving—isn’t that all of us, really?

Small Suggestions for Deeper Listening

For those encountering “The Swan” for the first time, I’d like to offer a few recommendations. First, seek out excellent cello performances, as the instrument’s tone and expressiveness form the piece’s very heart. Comparing interpretations by masters like Yo-Yo Ma, Mischa Maisky, or Jacqueline du Pré can be revelatory.

Second, this piece rewards repeated listening. Listen once for overall impression, again focusing solely on the cello melody, and a third time following the piano accompaniment’s subtle movements. Each hearing reveals new discoveries.

Finally, I recommend listening with eyes closed when possible. Without visual distractions, concentrating purely on sound allows the piece’s painted landscape to emerge with greater clarity. And if opportunity permits, try listening beside an actual lake or river—it becomes an extraordinarily special experience.

A Song of Timeless Beauty

“The Swan” has transcended classical music to become a cultural symbol. Anna Pavlova’s “The Dying Swan” ballet, Yuzuru Hanyu’s figure skating programs, countless arrangements and reinterpretations—all demonstrate that true beauty crosses temporal and genre boundaries.

Whenever I hear this piece, I wonder: How different were Saint-Saëns’ emotions in 1886 from what we feel today? Probably not very different at all. That sense of awe before beauty, melancholy about transience, and yet the will to continue living despite it all—these feelings dwell timelessly in the depths of human hearts.

“The Swan” speaks to us: Beautiful things fade, but remembering and transmitting that beauty is what we can do. And music serves precisely this role. When the cello’s final note dissolves into air, we encounter eternity within that lingering resonance.

Invitation to the Next Journey: Smetana’s Vltava

Our beautiful journey through classical music doesn’t end here. Following “The Swan’s” quiet emotional impact, why not embark on a more epic and sweeping musical voyage?

Smetana’s symphonic poem “Vltava (The Moldau)” musically depicts the majestic journey of the Vltava River, Bohemia’s lifeline, from its source springs through Prague to its confluence with the Elbe. If “The Swan” offered personal meditation upon a quiet lake, “Vltava” presents an epic narrative where national soul and natural grandeur interweave.

Two small springs merge into a mighty river, flowing through forests and meadows, witnessing peasant weddings and fairy dances, cutting through rugged gorges, finally reaching Prague. All of this unfolds vividly within Smetana’s musical canvas.

How wonderful would it be if our classical journey, beginning with “The Swan’s” delicate lyricism, continued toward grander emotional territories? Though both works share water’s flow as common ground, experiencing how differently they express this theme represents one of classical music appreciation’s greatest pleasures.