Table of Contents

A Shepherd’s Song from Somewhere Far Away

Some music transports us to another time and place the moment we hear it. That’s exactly what happened when I first encountered Bartók’s Romanian Folk Dances. The melodies flowing from the piano keys felt like shepherd’s songs carried on the wind from the fields of Transylvania. In just over five minutes, these six small dance movements tell stories that are remarkably vivid and sincere.

Before this music, I feel infinitely small. Not in the face of flashy virtuosity or grand scale, but simply before the power of pure melody. Have you ever had such an experience? Those moments when, amid life’s complexities, you suddenly encounter something simple yet profoundly true.

One Composer’s Passionate Journey

In 1915, Béla Bartók was more than just a composer. He was also an ethnomusicologist who traveled through the Hungarian and Romanian countryside with recording equipment, collecting songs from farmers and shepherds. This was a revolutionary approach for its time. What he sought was the pure voice of the people, untainted by the conventions of Western classical music.

Bartók and Kodály together traversed Central Europe, collecting thousands of folk melodies. For them, folk songs weren’t mere data but living heritage infused with the soul of the people. These Romanian Folk Dances represent one fruit of that passionate journey.

Interestingly, this work was originally titled “Romanian Folk Dances from Hungary.” But after Transylvania was incorporated into Romania in 1920, it became known by its current name. Even in a single title, the currents of history flow through.

Six Small Jewels

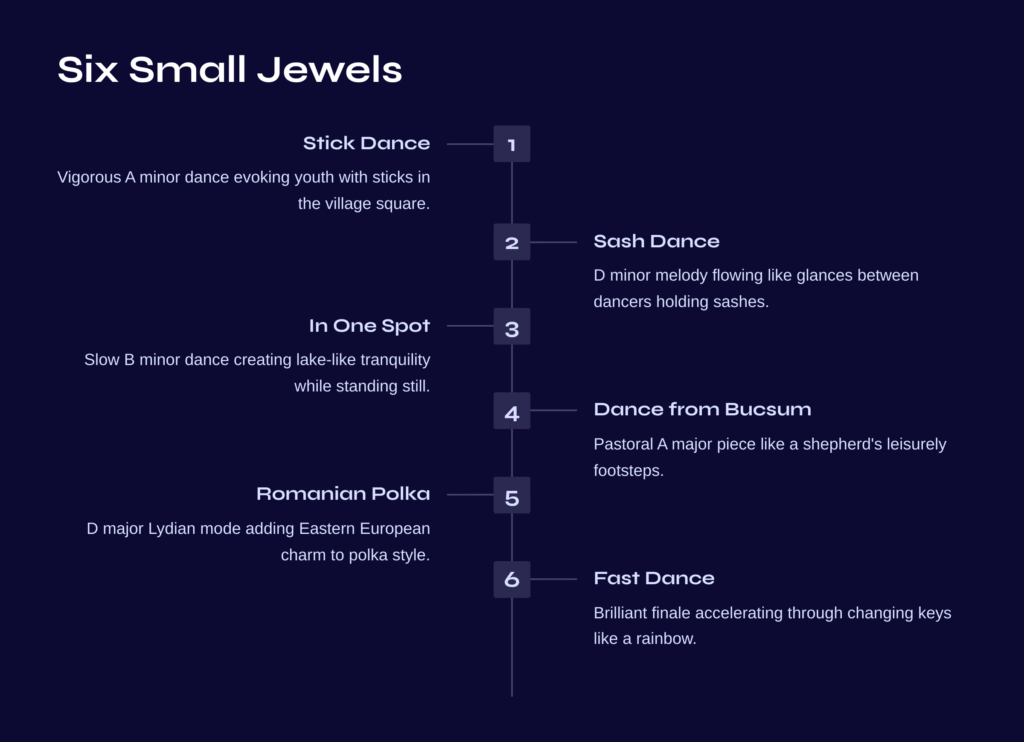

First Dance – Stick Dance (Jocul cu bâtă)

The first dance in Allegro moderato begins in A minor using the Dorian mode. But more important than these musical terms is the feeling this dance evokes. It’s like watching young people dance vigorously with sticks in the village square. The strong, rhythmic melody brings to mind feet striking the ground.

Second Dance – Sash Dance (Brâul)

Allegro tempo in D minor Dorian mode. This dance is traditionally performed by men and women holding sashes or handkerchiefs. Listening to the music, you can truly visualize such a scene. The melody flows back and forth like glances exchanged between two people.

Third Dance – In One Spot (Pe loc)

Suddenly the atmosphere changes. Andante’s slow tempo, B minor in “Romanian minor” mode. This dance is literally performed in one spot. But while the body stays in place, the soul seems to journey to deeper realms. Whenever I hear this section, I find myself in a lake-like state of tranquility.

Fourth Dance – Dance from Bucsum (Buciumeana)

Moderato tempo in A major Phrygian dominant mode. Bucsum is the name of a Romanian region. This dance has a pastoral peacefulness. It’s like hearing the leisurely footsteps of a shepherd driving his flock.

Fifth Dance – Romanian Polka (Poarga Românească)

Allegro in D major Lydian mode. Though called a polka, it has a unique charm different from Western polkas. The mysterious coloring of the Lydian mode adds Eastern European fragrance to the typical polka style.

Sixth Dance – Fast Dance (Mărunțel)

The final dance is the most brilliant. It accelerates from Allegro to Più Allegro while the key changes from D major to A major. From Lydian through Mixolydian to A Dorian mode, various modes flash by like a rainbow. It’s a fantastic finale decorating the end of the festival.

The Story That Reached Me

Listening to this music, I keep wondering: what is true beauty? What Bartók discovered in the Transylvanian countryside were simple melodies – neither sophisticated nor complex. Yet within them lay truths that had lived alongside people for hundreds of years.

In modern society, we’re increasingly surrounded by complex and flashy things. But sometimes we need music like this – simple yet deep, humble yet truthful. The reason these six small dance movements bring peace to a corner of our hearts lies precisely here.

Especially when I hear the third “In One Spot,” I’m overcome by strange emotions. The body remains in place, but the soul seems to travel elsewhere. Could this be the magic that Bartók discovered in folk songs?

Small Tips for Deeper Listening

Let me suggest a few points for appreciating this work. First, pay attention to the rhythm of each dance. Though they appear simple, subtle accents and variations are hidden within. Try listening as if following the actual footsteps of dancing people.

Second, listen to the colors of the modes. You’ll sense a unique atmosphere different from the major and minor scales familiar to us. The Lydian mode of the fifth polka has particularly mysterious charm.

Finally, I recommend comparing the piano and orchestral versions. The same melodies approach you with completely different colors. The piano is more direct and powerful, while the orchestra is richer and more pastoral.

The Magic of Melodies That Transcend Time

Bartók’s Romanian Folk Dances is truly a mysterious work. Though composed in 1915, the melodies it contains are much older. They might be songs people have been singing for hundreds, even thousands of years.

I truly understand what it means for music to transcend time. That we, living in completely different cultures and environments over a century later, can be moved by this music seems miraculous in itself. Songs once sung by Transylvanian shepherds now stir our 21st-century hearts.

So whenever I listen to this music, I think: isn’t true art a bridge connecting people across time and space? These small melodies that Bartók collected from the fields continue today to bring small reverberations to someone’s heart somewhere.

Perfect Follow-up – Schumann’s Träumerei

If Bartók’s simple yet profound folk melodies have warmed your heart, I recommend following with Schumann’s “Träumerei (Dreaming Child).” This piece, the seventh movement from Schumann’s “Scenes from Childhood,” sings of purity and truth in a completely different way from Bartók, yet with similar sincerity.

If what Bartók found in the Transylvanian fields was the primitive purity of a people, what Schumann captured in “Scenes from Childhood” was the emotional purity of childhood. Both composers painted essential beauty beyond complex reality through their music.

Particularly, Träumerei’s soft, dreamlike melody contrasts with Bartók’s folk vitality while mysteriously harmonizing with it. It’s like a child who has played in the fields all day quietly falling into dreams at evening. Listening to both pieces in succession allows you to feel even more deeply the healing power that music provides.