Table of Contents

Some Music Tells Beautiful Lies

Listening to the gentle 6/8 melody flowing from violin strings, I often find myself thinking that music sometimes tells the most beautiful lies. What is this strange emotion I feel every time I hear Maria Theresia von Paradis’s Sicilienne? Standing before this lyrical work allegedly composed by an 18th-century Austrian blind pianist, we find ourselves somewhere between musical truth and fiction.

The melody unfolding over the warm colors of E-flat major embraces us like a lullaby heard from a cradle. Yet behind this beautiful melody lies a great secret. Is this piece truly Paradis’s work?

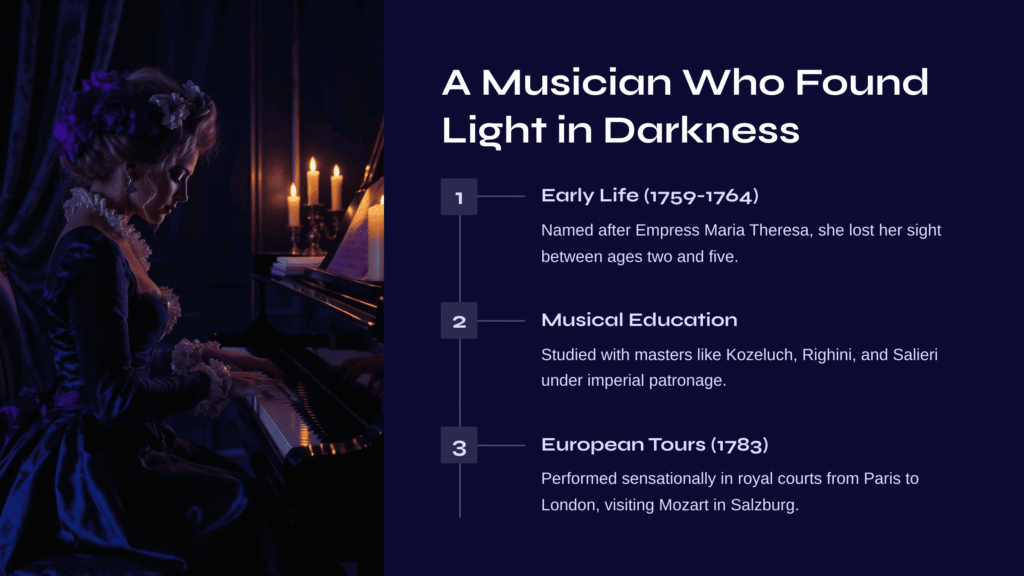

A Musician Who Found Light in Darkness

The life of Maria Theresia von Paradis (1759-1824) is itself a remarkable story. Named after Empress Maria Theresa, she gradually lost her sight between the ages of two and five, yet in that darkness discovered an even brighter world of music. Imagine her performing with over sixty concertos memorized, along with countless solo pieces and religious works etched in her mind.

Her musical education was of the highest standard for its time. She studied music theory and composition with Karl Frieberth, piano with Leopold Kozeluch, and voice with Vincenzo Righini and Antonio Salieri. All this took place under the special patronage of the imperial court.

Her European concert tours beginning in 1783 were nothing short of sensational. Performing in royal courts from Paris to London, she even visited the Mozart family in Salzburg. The story that Mozart composed his Piano Concerto No. 18 specifically for her remains a symbolic testament to her musical stature.

The Beautiful Whispers of Sicilienne

The moment one first hears Paradis’s Sicilienne, anyone becomes captivated by its special charm. Performed at an Andantino tempo, this piece resembles the warm Mediterranean breeze. The melody unfolding over the gentle sway of 6/8 time perfectly fits the description of a “generous, graceful and arching melodic line.”

The most enchanting aspect of this piece lies in its harmonic shifts that naturally move between major and minor modes. Like sunlight filtering through clouds, brightness and shadow interweave, subtly stirring the listener’s heart. The beauty of this melody over simple accompaniment explains why countless performers choose it as an encore piece.

From its original scoring for violin and piano, the piece has been arranged for cello and piano, flute and piano, and even trumpet with winds. From Nathan Milstein’s 1950s recordings to Jacqueline du Pré’s celebrated cello version, each performer has found their own unique color in this music.

Beautiful Lies and Hidden Truths

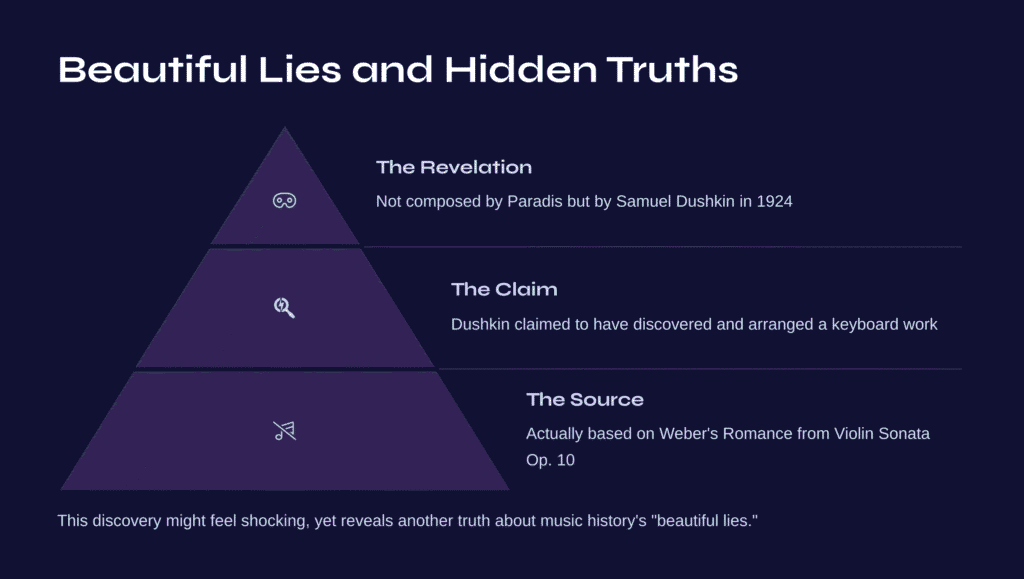

But here the story takes an unexpected turn. According to modern musicological research, this beautiful Sicilienne was not actually composed by Paradis but by violinist Samuel Dushkin in 1924, published by Schott.

Dushkin claimed to have discovered this piece as a keyboard work by Paradis and arranged it for violin and piano, but no such original exists. More intriguingly, this piece was actually based on material from Carl Maria von Weber’s Romance from his Violin Sonata Op. 10 No. 1.

This discovery might initially feel shocking. The music we’ve loved was fiction? Yet this simultaneously reveals another truth about music. Like Kreisler’s spurious attributions, Giazotto’s “Albinoni Adagio,” and Vavilov’s “Caccini Ave Maria,” classical music history contains such “beautiful lies.”

Weber’s Shadow, Dushkin’s Recreation

Carl Maria von Weber’s Romanza Siciliana was originally a work in G minor for flute and orchestra. True to early 19th-century Romantic style, Weber realized authentic Siciliana characteristics through sophisticated harmonic language and developmental techniques. Dushkin transformed this complex, refined work into a more accessible, simplified form.

Comparing the two works reveals fascinating differences. Weber’s original demonstrates the sophisticated compositional techniques of 19th-century Romanticism, while Dushkin’s version reflects the classical sensibilities preferred by early 20th-century performers and audiences. This represents not simple plagiarism, but the process of musical ideas transforming across time.

Melodies That Continue to Resonate

What then is the true value of this piece? The composer’s name changing doesn’t diminish its beauty. Today, countless violinists and cellists continue to perform this work, and music educators teach romantic expression through this piece to their students.

From David Garrett to Marina Chiche, contemporary performers breathe new life into this piece through their interpretations. The lyricism compressed into these brief 2-3 minutes continues to move people’s hearts. Through subtle tempo changes, different phrasing, and dynamic adjustments, each performer tells their own story.

The piece’s educational value remains unchanged as well. It serves as excellent material for developing sustained melodic playing, intonation control, and sensitivity to harmonic progression. It’s particularly helpful for cultivating chamber music skills through collaboration with piano accompaniment.

Searching for the Real Paradis

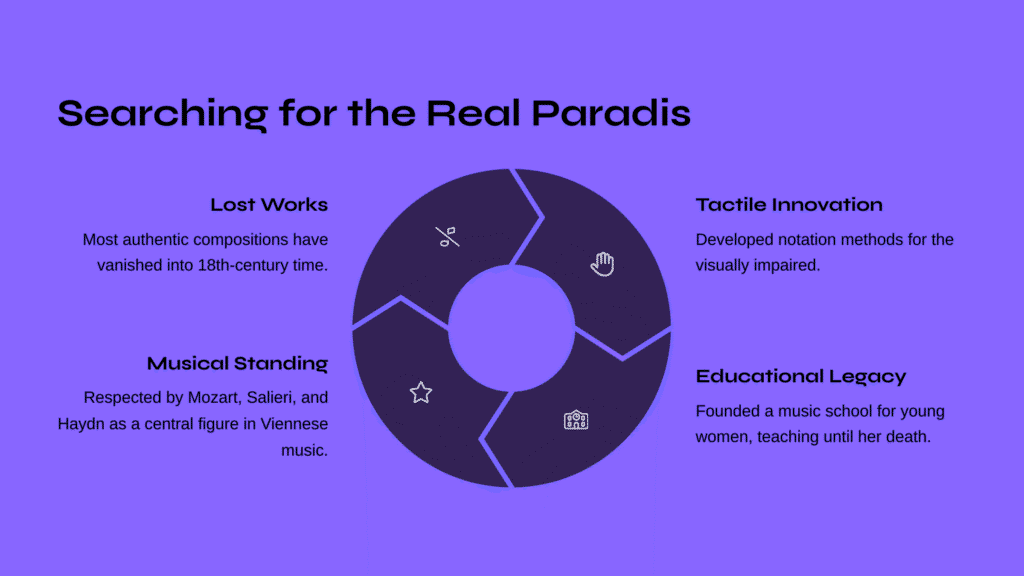

Most of Paradis’s authentic works have been lost. The cantatas, fantasies, sonatas, concertos, and stage music she actually composed have vanished into 18th-century time. This makes the false attribution of the Sicilienne particularly regrettable, as it obscures her genuine musical voice.

However, Paradis’s true legacy lies elsewhere. Her development of tactile notation methods, music education approaches for the visually impaired, and her influence on the Institute for Blind Youth established in Paris in 1784 represent her real contributions. Her founding of a music school for young women, where she taught until her death in 1824, was also a significant achievement.

The fact that Mozart, Salieri, Haydn, and other leading musicians of her era respected her demonstrates her musical standing. She was not merely a performer who overcame disability, but a central figure in 18th-century Viennese musical life.

Listening Points

Several points deserve attention when listening to this piece. First, feel the natural flow of 6/8 time. The rhythmic sense that flows like waves gently caressing the shore is the essence of this piece. Second, listen for the subtle changes between major and minor modes. The emotional nuances created by these harmonic shifts add depth to the music.

When choosing performance versions, approach thoughtfully. The violin version most directly conveys the melody’s lyricism, while the cello version expresses inner emotions through deeper, richer tones. Whichever version you choose, this piece reveals new aspects with each repeated listening.

Beauty That Transcends Time

Ultimately, this story leads to questions about music’s essence. Does the composer’s name determine musical value? Or does the music’s inherent beauty overwhelm everything else? Paradis’s Sicilienne offers one answer to these questions.

Dushkin’s piece being called by Paradis’s name might be another form of tribute. Though not actually a work by Paradis, reverence for her remarkable life and musical achievements is transmitted through this beautiful melody.

Music sometimes crosses time in this way. The meeting of an 18th-century Viennese blind pianist with a 20th-century violinist, and our 21st-century emotions, all converge within a single melody. Truth and fiction, history and present harmonize while resonating within E-flat major’s gentle chords.

This is the gift that classical music gives us. An emotional bridge that crosses time and space, transmitting directly from one heart to another. Paradis’s Sicilienne continues to sing quietly on that bridge today.

Next Destination: Vaughan Williams’s Tallis Fantasia

If Paradis’s Sicilienne was an 18th-century dream created in the 20th century, Ralph Vaughan Williams’s “Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis” represents a genuine dialogue leaping across 400 years to meet a 16th-century soul.

Premiered at Gloucester Cathedral in 1910, this work was written for the unique scoring of double string orchestra and string quartet. Based on “Why fum’th in fight,” the third of nine melodies Thomas Tallis composed for Archbishop Matthew Parker’s Psalter in 1567, this fantasia demonstrates true historical encounter, unlike Paradis’s Sicilienne.

The “full, shimmering sound” and “flowing, interwoven themes” created by the strings resemble prayers echoing from cathedral heights. Vaughan Williams wrapped Tallis’s Phrygian mode melody in 20th-century harmonic language while preserving the spirit of 16th-century Renaissance. Isn’t this what genuine musical dialogue across time truly means?