Table of Contents

First Encounter – A Handshake Across 400 Years

Some music stops time in its tracks. And then leads us into another world entirely. How can I describe the sensation of hearing Ralph Vaughan Williams’ “Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis” for the first time? It was like waking on a misty dawn and opening the window—familiar yet strange air seeping deep into my lungs.

The moment when a 16th-century hymn melody by Thomas Tallis is reborn through the hands of a 20th-century composer. This wasn’t mere arrangement but a conversation between two souls across centuries. The sound created by an orchestra of strings alone was sometimes quiet as a whisper, sometimes grand as a choir filling cathedral arches.

Listening to this piece, I realized something profound: music is ultimately the art of time, yet it’s also the art that most perfectly betrays time. When a 400-year-old melody reaches my ears today, time loses all meaning.

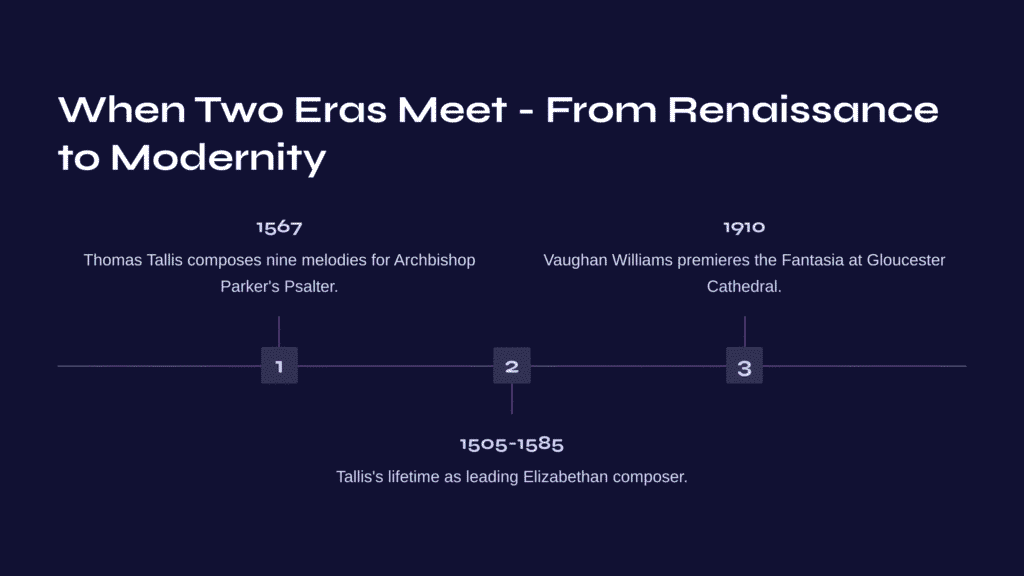

When Two Eras Meet – From Renaissance to Modernity

Premiered in 1910 at Gloucester Cathedral, this work marked not simply the birth of a new composition, but a crucial turning point in English musical history. The 38-year-old Vaughan Williams was searching for his unique musical identity, and through his editorial work on the English Hymnal, he discovered his answer in Thomas Tallis’s haunting melody.

Thomas Tallis (1505-1585) was a leading composer of the Elizabethan era. The third of nine melodies he composed in 1567 for Archbishop Matthew Parker’s Psalter became the foundation for this fantasia. Originally written for Psalm 2—”Why do the heathen rage, and the people imagine a vain thing?”—this poignant and mysterious melody possessed a power that transcended religious boundaries to speak to universal human emotions.

What Vaughan Williams discovered in Tallis’s melody wasn’t simply a beautiful tune. It was an ambiguous and mystical sound world constructed in the Phrygian mode—neither major nor minor. This ancient modal system created a special coloration that sounds unfamiliar to modern ears, yet perhaps for that very reason, resonates with deeper meaning.

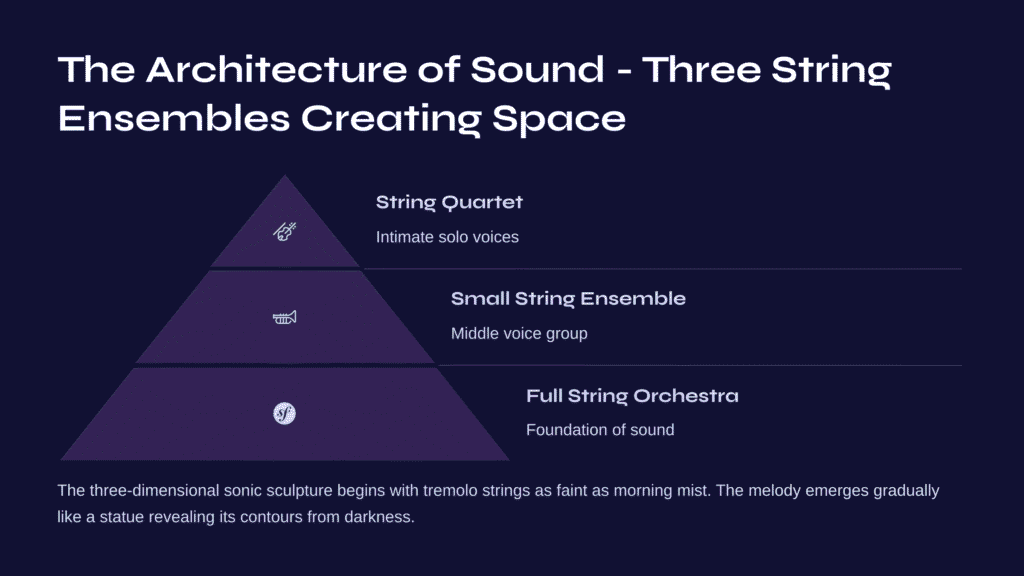

The Architecture of Sound – Three String Ensembles Creating Space

The most distinctive feature of this fantasia lies in its orchestration. Vaughan Williams added a smaller string ensemble and a string quartet to the standard string orchestra. When these three groups are spatially separated in performance, the music transcends simple melody and harmony to become three-dimensional sonic sculpture.

The piece begins with tremolo strings as faint as morning mist. When the pizzicato of the lower strings hints at Tallis’s melody, the complete picture gradually emerges. This isn’t theme presentation but the “birth” of a theme. Like a statue slowly revealing its contours from darkness, the melody passes through several stages before achieving its complete form.

The first complete statement of the theme is quiet and reverent. But in the second presentation, high violins sing the melody while richer harmonic support is added below. From this point, the music begins to grow increasingly complex.

In the development section, Vaughan Williams deconstructs and reconstructs Tallis’s melody. The first and second halves are played by different instrumental groups, sometimes conversing, sometimes overlapping, exploring new sonic possibilities. Here the composer’s genius shines. He recreates ancient melody in entirely new contexts without destroying its essential character.

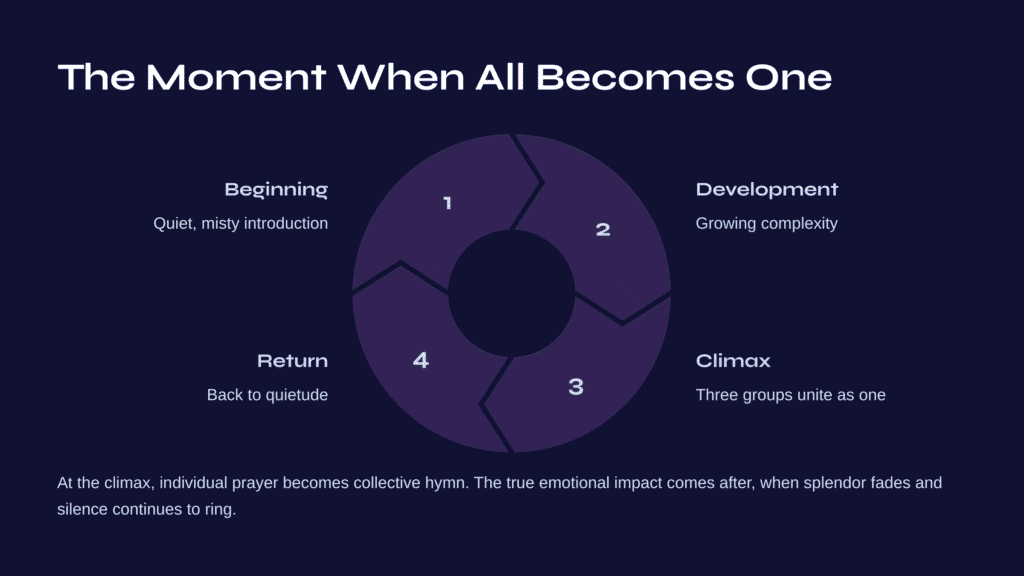

The Moment When All Becomes One

At the fantasia’s climax, the three string groups finally unite as one massive sonic entity. The music here transcends individual prayer to become collective hymn, approaching cosmic chorus. That Tallis’s humble hymn tune could transform into such grandeur is itself miraculous testimony to music’s transformative power.

But the true emotional impact comes after the climax. When all the splendor fades and we return to the original quietude. When the lone remaining melody dissolves into air. Though the music has ended, we remain suspended in its resonance. This is the power of great music—a silence that continues to ring after the sound has stopped.

What I Discovered in This Music

Through repeated listening, I reached a profound realization: true beauty doesn’t emerge from complexity but from the depths of simplicity. Tallis’s melody itself is never complex—rather, it’s remarkably humble and direct. Yet Vaughan Williams discovered infinite possibilities hidden within that simplicity.

Sometimes I sit alone in a quiet room, eyes closed, listening to this piece. In those moments, I can simultaneously feel both Tallis’s melody that once echoed through a 16th-century English cathedral and the heart of Vaughan Williams who was moved by hearing it. Music is like a bridge connecting human hearts across time and space.

Especially when I’m exhausted by modern life’s relentless pace, this music offers me a different flow of time. Not the rushed time of daily life, but inner time for deep contemplation. Within that space, I find true rest.

Suggestions for Deeper Listening

If you’re hearing this piece for the first time, I recommend patience. In your first listening, follow the overall flow—notice how the music begins quietly, builds to a massive climax, then returns to silence.

On second hearing, pay attention to how the three string groups converse with each other. If possible, listen through good speakers rather than headphones. The spatial effects of this piece require dimensional sound to be properly experienced.

From the third listening onward, try tracking how Tallis’s original melody is transformed and developed. Like assembling puzzle pieces, each time the familiar melody appears in new guise, you’ll marvel at the composer’s creativity.

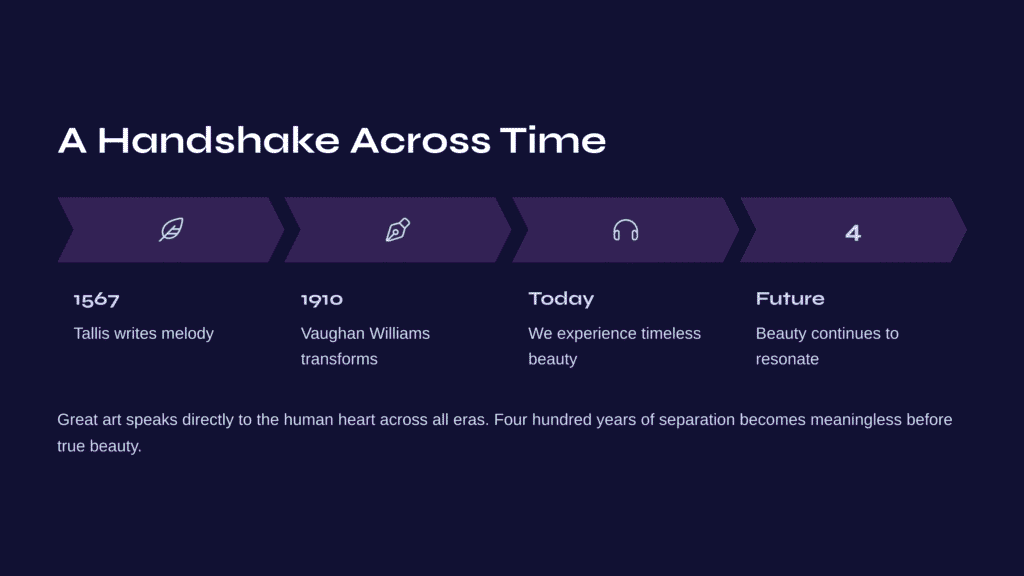

A Handshake Across Time

Vaughan Williams’ “Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis” shows us a moment when past and present clasp hands. The process by which a 16th-century humble hymn meets 20th-century sophisticated orchestration to gain new life. This transcends mere musical experiment to become living proof that tradition and innovation can coexist harmoniously.

After listening, this thought emerges: ultimately, great art speaks directly to the human heart across all eras. Four hundred years of separation, differences in language, differences in cultural background—all become meaningless before true beauty.

From Tallis writing that melody with his pen in 1567, through Vaughan Williams’ baton at Gloucester Cathedral in 1910, to reaching our ears today—at the end of this long journey, we encounter beauty in its purest, timeless form. And it will continue to resonate in the hearts of future generations.

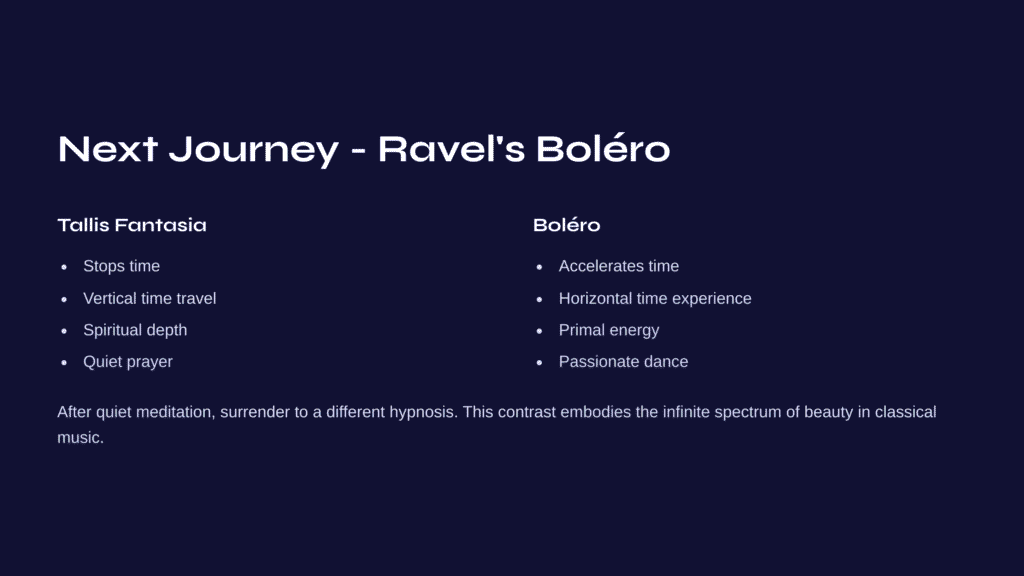

Next Journey – Ravel’s Boléro

After completing the quiet meditation of the Tallis Fantasia, how about surrendering to a completely different kind of hypnosis? Maurice Ravel’s “Boléro” treats time in the exact opposite way from Vaughan Williams. If the Tallis Fantasia stops time, Boléro accelerates it.

This piece—with a single melody repeated relentlessly for 15 minutes while gradually growing in intensity—is the hypnotism of repetition. If the Tallis Fantasia is vertical time travel connecting past and present, Boléro is horizontal time experience that stretches the present moment to its limits. Both pieces begin with simplicity, but one moves toward spiritual depth while the other heads toward primal energy.

After Tallis’s quiet prayer, we encounter Ravel’s passionate dance. This contrast embodies the infinite spectrum of beauty that classical music embraces.