📑 Table of Contents

There’s a particular kind of silence that descends on Christmas Eve—not an absence of sound, but a hush pregnant with expectation. The world seems to hold its breath. Streets empty. Candles flicker in windows. And somewhere in the darkness, you can almost hear footsteps approaching from distant hills.

Over three hundred years ago, Arcangelo Corelli captured this exact moment in music. His Pastorale from the Christmas Concerto doesn’t simply accompany the holiday season—it becomes that sacred stillness, that gentle anticipation, that whispered reverence of shepherds kneeling before something greater than themselves.

If you’ve ever yearned for a piece of music that could slow time itself, that could wrap you in warmth like a wool blanket on a winter’s night, this is it.

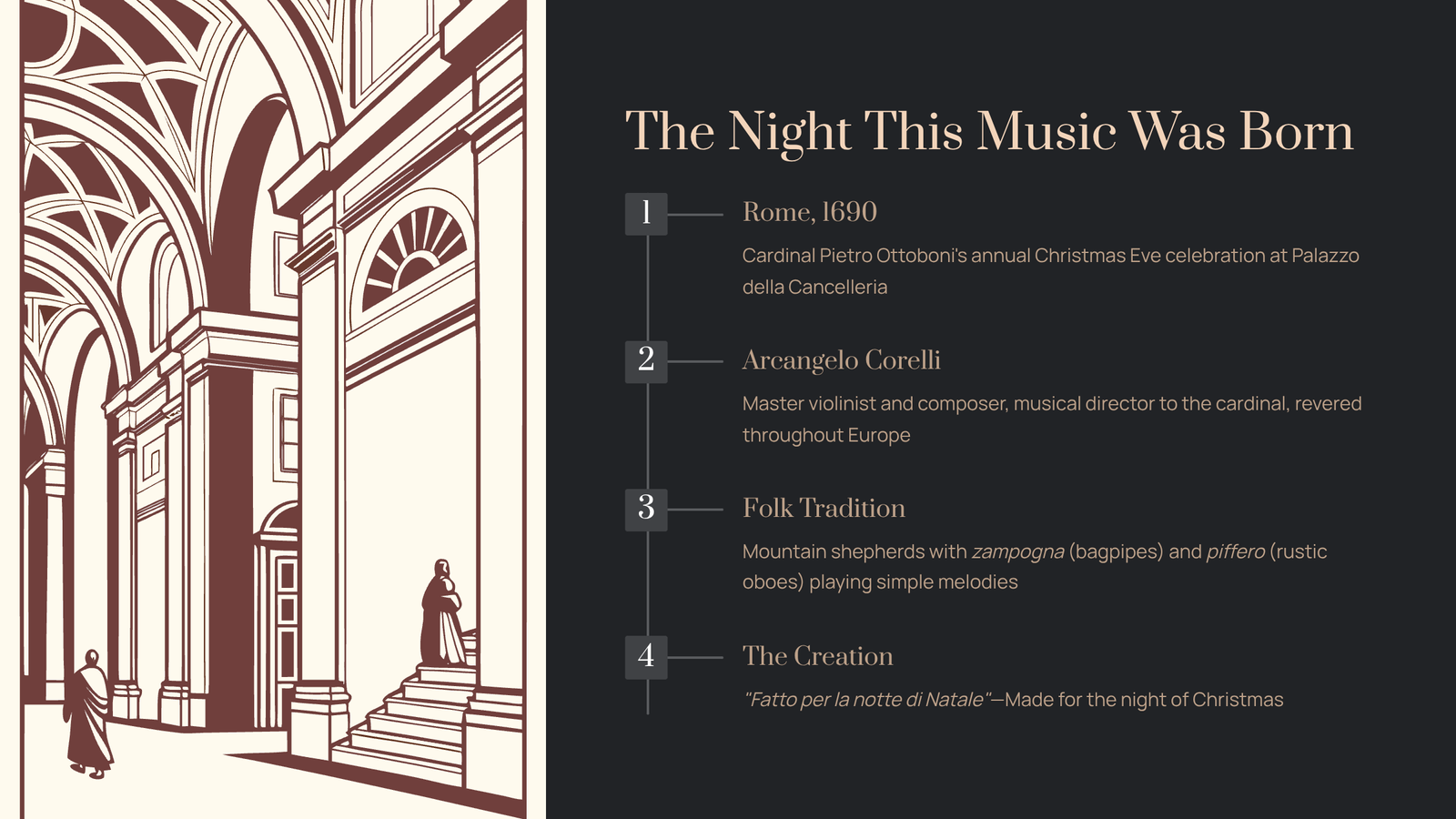

Rome, 1690. In the opulent halls of the Palazzo della Cancelleria, Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni—nephew to Pope Alexander VIII and one of the most powerful patrons of the arts in Europe—hosted his annual Christmas Eve celebration. The flickering candlelight illuminated frescoed ceilings as Rome’s elite gathered in hushed anticipation.

At the center of this evening stood Arcangelo Corelli, violin in hand, preparing to unveil something extraordinary.

Corelli wasn’t merely a composer. He was the acknowledged master of the violin, a musician so revered that his contemporaries spoke of him in terms usually reserved for saints. For nearly a decade, he had served as Ottoboni’s musical director, transforming the cardinal’s palace into the epicenter of Roman musical life.

But the music he prepared for this particular Christmas Eve drew from something far older than courtly elegance. Throughout Italy, a folk tradition persisted: during the nine days before Christmas, mountain shepherds descended into villages with their zampogna—Italian bagpipes—and piffero—rustic oboes. These pifferari played simple, drone-based melodies outside homes and churches, reenacting the journey of Bethlehem’s shepherds who came to worship the newborn Christ.

Corelli took this humble tradition and wove it into the sophisticated fabric of Baroque composition. The result was marked on his score with an inscription that still resonates: “Fatto per la notte di Natale”—Made for the night of Christmas.

Anatomy of Stillness: What Makes This Music So Peaceful

The Pastorale movement—the sixth and final movement of the Christmas Concerto—achieves its extraordinary tranquility through several ingenious musical choices.

The drone bass serves as the movement’s foundation. Throughout the piece, the lower strings sustain long, unwavering notes—typically the home note of G—while melodies float above them. This technique directly imitates the zampogna’s constant drone, that hypnotic hum that mountain bagpipes produce as melodic fingers dance above. The effect is profoundly grounding, like an anchor keeping a ship steady in calm waters.

The time signature of 12/8 creates what musicians call a siciliano rhythm—a gentle, lilting pulse that suggests rocking motion. Think of a boat swaying on still water, or a mother cradling an infant. This rhythmic quality gives the Pastorale its characteristic sense of peaceful movement without urgency.

Perhaps most striking is the harmonic journey. The preceding five movements of the concerto unfold in G minor—a key traditionally associated with seriousness, even melancholy. Then, without warning, the Pastorale opens in G major. It’s as if dawn breaks after a long night. Light enters where shadow once dwelt. This transformation from minor to major mirrors the Christmas narrative itself: hope arriving in darkness, light entering the world.

The melodies move primarily in parallel thirds—two voices traveling together, never far apart, like companions walking in step. This intervallic relationship creates inherent sweetness, an almost naive simplicity that suggests the unpretentious devotion of shepherds rather than the elaborate worship of kings.

A Listening Journey: How to Experience This Music

First listening: Simply receive. Don’t analyze. Don’t think about structure or technique. Find a quiet space, perhaps light a candle, and let the music wash over you. Notice how your breathing naturally slows. Pay attention to how the sustained bass notes seem to support everything above them, like the earth supporting a cathedral.

Second listening: Follow the conversation. The Concerto Grosso form creates a dialogue between two groups: the concertino (a small group of solo instruments) and the ripieno (the full ensemble). Listen for moments when the solo violins step forward with intimate phrases, then retreat as the larger group responds. It’s like overhearing whispered confidences followed by murmured agreement.

Third listening: Feel the night. Close your eyes and imagine yourself on a hillside outside Bethlehem. The air is cold but still. Stars crowd the sky. Somewhere below, a light glows in a stable. The music you’re hearing is the sound of that night—not the grand proclamations of angels, but the quiet wonder of ordinary people witnessing something extraordinary. Notice how the melody never climbs to dramatic heights or plunges to tragic depths. It simply abides, content to exist in gentle reverence.

The Beautiful Mystery of “Ad Libitum”

Here’s a curious detail that reveals something profound about this music. On Corelli’s original score, the Pastorale is marked “ad libitum”—meaning “at pleasure” or “optional.” The concerto could technically end with the fifth movement’s energetic Allegro.

Why would Corelli make his most beloved movement optional?

The answer lies in liturgical practice. During Christmas Eve mass, different sections of the service required different musical accompaniments. The Pastorale was designed to be performed during the offertory—a specific moment in the ceremony. If the mass didn’t call for it, the movement could be omitted.

Yet here’s what speaks to the movement’s transcendent beauty: no one omits it anymore. In three centuries of performance, the Pastorale has become inseparable from the concerto itself. What was marked as optional became essential. What was meant to be supplementary became the heart of the work.

This transformation—from dispensable to indispensable—might be the highest compliment music can receive. Performers and audiences across three hundred years have collectively decided: this movement is too beautiful to leave unplayed.

Recordings That Capture the Magic

Several interpretations offer distinct windows into this music.

Voices of Music presents a historically informed performance that particularly emphasizes the connection to zampogna tradition. Their recording captures what they call the “epic drone notes” with remarkable clarity, using period instruments that bring us closer to what Corelli himself might have heard in Cardinal Ottoboni’s palace.

Concerto Copenhagen under Lars Ulrik Mortensen offers an interpretation that highlights the siciliano rhythm’s gentle swaying motion. Mortensen treats the concerto with both scholarly rigor and genuine affection, calling the Pastorale a kind of “pop tune” of its era—beloved by everyone who encountered it.

For those curious about how this music sounds in a cinematic context, Richard Tognetti and the Australian Chamber Orchestra recorded material from the Christmas Concerto for the film Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World (2003). While the film prominently features the third movement, their approach to Corelli showcases how this centuries-old music still speaks to contemporary audiences.

What the Shepherds Understood

There’s a reason this music has endured for over three centuries while countless other Baroque compositions have faded into obscurity. Corelli captured something essential about the Christmas moment—not the bustle of shopping or the frenzy of preparation, but the stillness at the heart of the season.

The Pastorale reminds us that the original witnesses to the Christmas story weren’t scholars or aristocrats. They were shepherds—people who lived close to the earth, who knew the patience required to tend flocks through long nights, who understood that some things can’t be rushed or forced but only waited for in humble expectation.

When you listen to Corelli’s Pastorale, you’re not just hearing beautiful music. You’re participating in a tradition that stretches back through centuries of candlelit churches, Roman palaces, and Italian hillsides where shepherds played their simple instruments under star-filled skies.

The drone bass that sustains the entire movement suggests something eternal—a presence that doesn’t waver, a foundation that holds firm. Above it, melodies rise and fall like prayers, like breath, like the heartbeat of wonder itself.

This Christmas Eve, when the world grows quiet and the candles burn low, let Corelli’s shepherds play for you. Let their ancient music remind you that sometimes the most profound experiences arrive not in thunder and spectacle, but in stillness, in patience, in the gentle revelation that some things are simply worth waiting for.

Fatto per la notte di Natale. Made for the night of Christmas. Made for you.