Table of Contents

Like Musical Notes Drawing Arabian Patterns

One afternoon, a melody flowing across piano keys captured my heart completely. It was like the concentric circles made by a small stone thrown into a still lake—calm yet carrying profound resonance. Robert Schumann’s Arabeske in C Major, Op. 18—just a few minutes of music, but within it flowed the complete emotional landscape of a composer, tracing elegant curves through time.

When you hear the word Arabeske, what comes to mind? I think of those graceful curves adorning the walls of Islamic palaces—endlessly flowing yet never monotonous, creating patterns of exquisite beauty. This is precisely why Schumann chose this title. He wanted to achieve that same aesthetic of curves within his music.

1839: The World Young Schumann Dreamed Of

The year 1839, when Robert Schumann composed this Arabeske, was extraordinary for him. He had settled in Leipzig, thriving both as a music critic and composer. Most importantly, it was when his love for Clara reached its peak.

In the heart of the Romantic era, Schumann aspired to write literature through music. He wrote in his diary: “I want to translate fantastic dreams and painterly images into musical compositions.” This Arabeske was precisely the fruit of such experimentation.

The piano miniature genre itself was the most favored form among Romantic composers of the time—think of Chopin’s nocturnes or Liszt’s impromptus. But Schumann’s approach was different. Rather than showcasing technical virtuosity, he was more interested in painting landscapes of the soul.

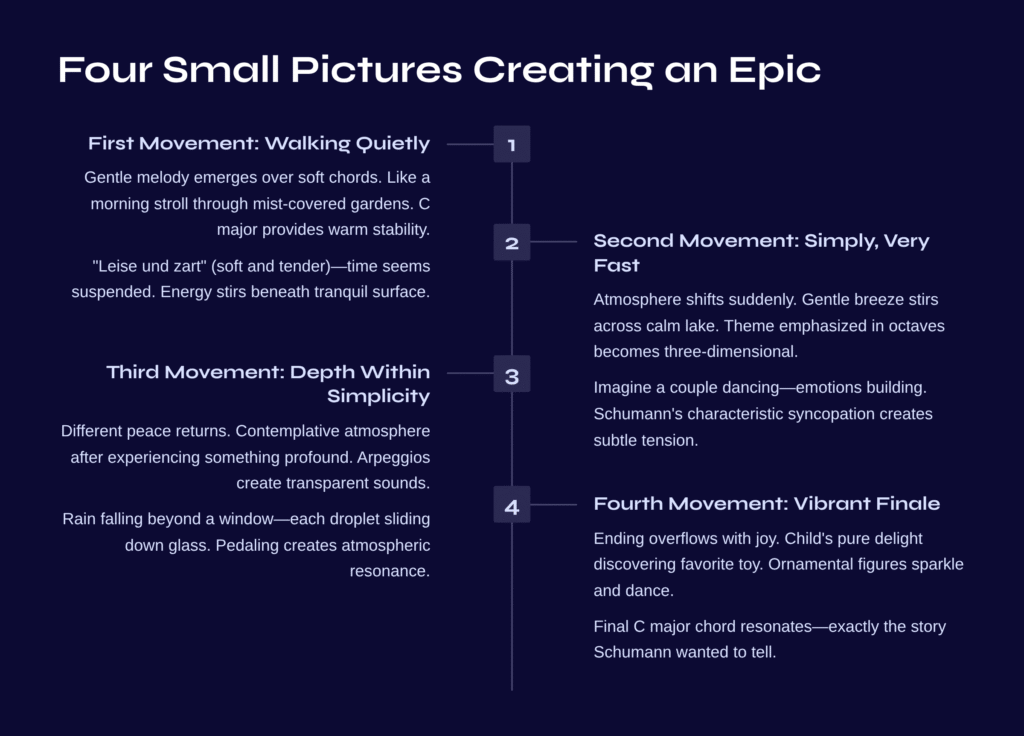

Four Small Pictures Creating an Epic

First Movement: “Walking Quietly”

As the piece begins, a gentle melody in the right hand emerges slowly over soft chords in the left hand. It feels like taking a morning stroll through a mist-covered garden. The bright, warm colors of C major provide stability, while the melody breathes naturally like flower petals swaying in the breeze.

True to Schumann’s marking “Leise und zart” (soft and tender), this section is unhurried. Time seems suspended, almost frozen. Yet within this tranquility, you can sense energy stirring beneath the surface.

Second Movement: “Simply, and Very Fast”

The atmosphere shifts suddenly. But rather than explosive, it’s more like a gentle breeze beginning to stir across a calm lake. As the theme emphasized in octaves appears, the music becomes more three-dimensional, and the rhythmic vitality awakens.

Whenever I hear this section, I imagine a couple dancing—not passionately, but with emotions clearly building. Schumann’s characteristic syncopation creates subtle tension that intensifies this feeling.

Third Movement: “Depth Within Simplicity”

Silence returns, but it’s a different kind of peace than before. Like the calm after a storm, there’s a contemplative atmosphere of having experienced something profound. Within the transparent sounds created by arpeggios, the melody returns in a more purified form.

This section always makes me envision rain falling beyond a window—each droplet sliding down the glass pane. The pedaling creates exactly this kind of atmospheric resonance.

Fourth Movement: “Vibrant Finale”

The ending overflows with joy, but not in the grand manner of a Beethoven symphony finale. It’s more like a child’s pure delight upon discovering a favorite toy. Ornamental figures sparkle and dance, while trills create tremors that seem almost like laughter.

When the final chord in C major resonates, I always think: “Ah, this is exactly the story Schumann wanted to tell.”

The Arabeske Drawn in My Heart

When I first heard this piece, I realized how truly visual music could be. I could literally see Arabian patterns unfolding before my eyes—curves continuing, intersecting, and converging again into unity.

But it wasn’t merely beautiful. Hidden between those curves were human emotions—joy, longing, and sometimes small sorrows. Particularly in those quiet moments of the third section, I felt as though I was glimpsing into Schumann’s own inner world.

His love for Clara and all the complex emotions that love brought—everything seems compressed into this small piece. It’s no coincidence that he dedicated the work to Clara.

Sometimes when life becomes difficult, I listen to this piece. It calms my heart while simultaneously filling me with a kind of hope—the realization that such beautiful moments still exist in this world.

Small Secrets for Deeper Listening

First Secret: The Magic of Pedaling

To properly appreciate this piece, pay attention to the pedaling. Especially in the third section’s arpeggios, how the performer uses the pedal completely transforms the piece’s atmosphere. Listening with headphones helps you catch these subtle differences more clearly.

Second Secret: Freedom of Tempo

Schumann loved using rubato (flexible tempo changes). In this piece too, look for performances that flow naturally like storytelling rather than maintaining mechanically precise beats. Maurizio Pollini and András Schiff’s interpretations are particularly excellent in this regard.

Third Secret: The Power of Repeated Listening

Since this piece is short, you can listen to it multiple times. First for the overall flow, second focusing on the melody, third following the harmonic changes. Each listening reveals new discoveries.

Timeless Beauty of Curves

Music is truly mysterious. The emotions felt by a composer over 180 years ago continue to live and breathe in our hearts today. Schumann’s Arabeske stands as testament to such timeless communication.

Every time I hear this piece, I reflect: perhaps true beauty lies not in complexity and grandeur, but in something simple yet sincere like this. The musical arabeske Schumann created isn’t mere decoration—it’s the most beautiful curve drawn by a human heart.

Next time you listen to this piece, close your eyes and trace those curves with your heart. You’ll surely draw your own unique arabeske. And in that moment, I believe you’ll join the beautiful conversation that Schumann and Clara once shared.

Next Journey: Walking Through Mists with a Czech Poet

If you’ve been enchanted by Schumann’s curved lines, why not venture into a more mysterious world? I recommend Leoš Janáček’s “In the Mists (V mlhách) – I. Andante”.

Composed in 1912, this work comes 70 years after Schumann, yet in its introspective beauty, we find curious parallels. Janáček, a composer from Czech Moravia, infused his music with the phantasmagorical colors unique to Eastern Europe.

True to its title “In the Mists,” this piece evokes the atmosphere of slowly walking through a fog-shrouded forest at dawn. If Schumann’s Arabeske represented elegant curves, Janáček’s work feels like a hazy watercolor painting.

Particularly the first movement’s Andante creates an atmosphere where time seems suspended, with fragmentary melodies emerging intermittently like shards of memory. It’s a work where modern harmonies creating mysterious soundscapes blend exquisitely with traditional melodic beauty.

From Schumann’s warm romanticism to Janáček’s mystical modernism—such musical journeys represent the true joy of classical music appreciation.

Recommended recordings to accompany this article:

– Maurizio Pollini (DG) – Restrained and transparent interpretation

– András Schiff (ECM) – Free rubato with deep contemplation

– Martha Argerich (DG) – Dramatic and emotional expression