Table of Contents

Like a Memory of Some Night

Certain pieces of music create the illusion that we’ve known them long before we first heard them. Shostakovich’s Waltz No. 2 is exactly such a piece. The moment that cool alto saxophone melody begins to flow, it feels as though some longing that had been sitting quietly in a corner of our hearts suddenly awakens.

This waltz is graceful, but never sweet. Even within the gentle sway of 3/4 time, there’s an unsettling shadow that seeps through. Like someone dancing alone at a corner table in a café—beautiful, yet lonely. When I first heard this piece, I couldn’t understand why my chest felt so heavy. Looking back now, I think it was the weight of time.

A Composer’s Hidden Story

Dmitri Shostakovich was a giant of 20th-century Soviet music, but his life was always lived under political tension. From the Stalin era through Khrushchev’s Thaw, he had to constantly walk a tightrope between official duty and personal expression.

Interestingly, our beloved Waltz No. 2 was originally composed as background music for the 1955 film “The First Echelon.” However, the process by which this piece became widely known to the world is quite complex. Not the composer himself, but an arranger named Levon Atovmyan collected various film music by Shostakovich and reconstructed it into an eight-movement “Suite for Variety Orchestra,” with Waltz No. 2 serving as the seventh movement.

Even more intriguing is the fact that this piece was long mistakenly known as “Jazz Suite No. 2.” Due to a footnote error in the 1984 Soviet complete works edition, the name of another, actually lost work was attached to this piece. The truth wasn’t revealed until 1999. Such twists and turns seem to add to the mysterious charm of this music.

Three Stories Told by Saxophone

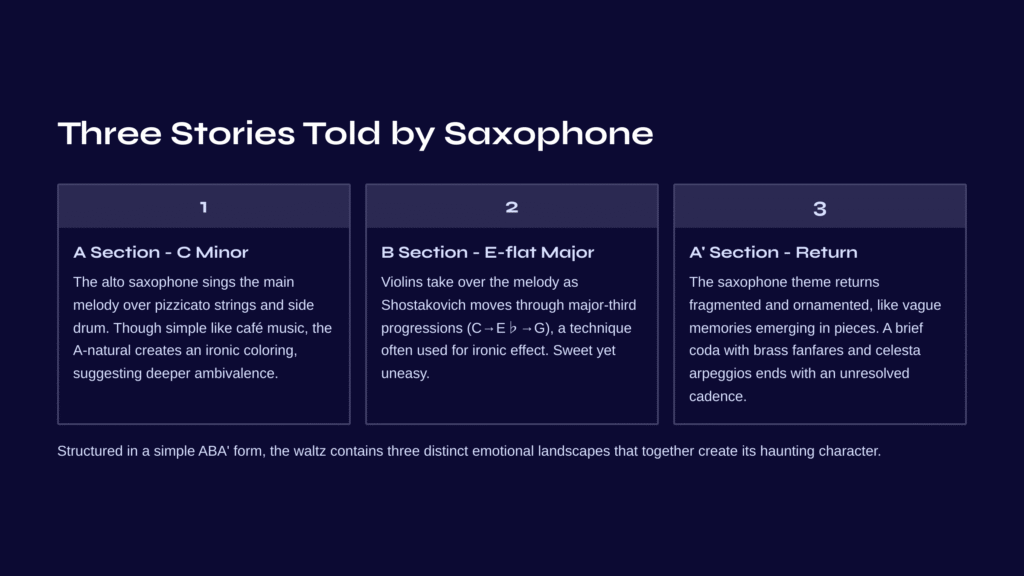

Waltz No. 2 is structured in a simple ABA’ form, but within it lie three different emotions.

The first A section begins in C minor. The alto saxophone sings the main melody over pizzicato strings and side drum accompaniment. This melody descends in thirds while outlining the C minor tonic, but the A-natural that appears midway creates a strangely ironic coloring. It appears simple like café music, but chromatic changes suggest deeper ambivalence.

The second B section modulates to E-flat major, with violins taking over the melody. Here, Shostakovich moves the harmony through major-third progressions (C→E♭→G), a technique he often used for ironic effect. The strings flow sweetly with the melody, yet somehow an uneasy atmosphere permeates.

In the returning A’ section, the saxophone theme appears fragmented and ornamented. Like memories becoming vague and emerging in pieces. Then in a brief coda, brass fanfares and celesta arpeggios appear, followed by a sudden diminuendo ending with an unresolved cadence. This is also a typical Shostakovich characteristic.

The Layers of Time I Felt

Each time I listen to this piece, I seem to experience multiple layers of time simultaneously. On the surface, the time of an elegant 3/4 waltz flows, but within it, other times intersect.

The first is the time of 1950s Soviet Union. Stalin had died and breathing space was gradually opening up, but the atmosphere of that era when one still had to walk carefully can be felt. Superficially a bright and cheerful dance piece, but through the dark shadows created by the minor tonality and dissonance, we can read the complex emotions of that time.

The second is time within personal memory. It’s no coincidence that this piece became known worldwide after being used in Stanley Kubrick’s “Eyes Wide Shut.” The melody flowing through the film’s masked ball scene perfectly captures moments where reality and fantasy, past and present intermingle.

The third is the eternal time created by the music itself. Even after the waltz ends, its melody continues to resonate in our hearts. Like a perpetual motion that seems never to end, it seems to dance eternally in our memory.

Three Points for Deeper Listening

First, pay attention to the saxophone’s timbre. It was extremely rare for alto saxophone to carry the main melody in early 20th-century Soviet orchestral works. This instrumental choice itself creates a cabaret atmosphere and reveals a secret longing for Western jazz culture.

Second, feel the subtle rhythmic changes. While traditional Viennese waltz emphasizes 1-2-3, this piece places stress on beats 1 and 3. Such irregular rhythmic feel and syncopation subtly disturb the dancer’s balance, creating a parodic effect.

Third, observe the uniqueness of the instrumentation. The doubling of celesta and piano adds cold sparkle to the string melodies, while accordion maintains harmonic pads, evoking the atmosphere of 1950s Soviet dance halls. These coloristic choices come together to create this piece’s distinctive sound.

A Melody That Transcends Time

Shostakovich’s Waltz No. 2 began as part of film music and became a classical masterpiece that captured hearts worldwide. That journey itself is evidence of music’s power to transcend time and space.

Every time I listen to this piece, I think about music’s mysterious ability. That a 3-minute, 40-second piece of music created by a Soviet composer 60 years ago for a film can so deeply move our hearts today. What is the essence of that resonance that transcends eras and systems, crossing languages and cultures?

Perhaps it’s some universal longing shared by all humans. The yearning for beauty and simultaneously the sadness that it’s not eternal. The desire to dance but the loneliness of dancing alone. Shostakovich captured all these complex emotions in just one waltz, and that melody continues to dance eternally in our hearts even now.

Next Recommendation: Clara Schumann’s Piano Trio in G minor, 2nd Movement

If Shostakovich’s waltz shows us the complex inner world of a 20th-century male composer, Clara Schumann’s Piano Trio in G minor, 2nd movement offers an experience of the delicate and profound sensibility of a 19th-century female composer.

The second movement of this trio, composed in 1846, is written in the same G minor as Shostakovich’s waltz. However, the melancholia felt here is more direct and personal. Clara was known only as Robert Schumann’s wife, but she was actually an excellent pianist and composer in her own right. In this movement, she sings of love and separation, and the internal conflicts of being a woman, in her own musical language.

If Shostakovich’s waltz expressed personal emotions hidden within social context, Clara’s music is more honest and direct. Through the intimate dialogue created by piano, violin, and cello, you can glimpse the sincere heart of a female artist.